In New Jersey, open space sacrificed for cheaper natural gas

Katie Colaneri/StateImpact Pennsylvania

Farmer Rob Fulper stretches his arms out to show the path of a natural gas pipeline that runs under one of his corn fields in West Amwell, NJ.

Open space is a rare commodity in New Jersey, the most densely populated state in the country.

The New Jersey Conservation Foundation says a proposed natural gas pipeline could cut through about 4,500 acres of undeveloped land preserved with public dollars.

If built, backers of the PennEast pipeline say it would feed cleaner fuel to power plants and bring cheaper gas to customers.

Now, the pipeline is forcing residents in the state’s highly-valued bucolic communities to weigh the environmental costs of moving natural gas to the marketplace.

“They can’t cross my farm now”

If you ever visit Rob Fulper’s 100-year-old family farm in West Amwell, New Jersey or meet his troupe of inquisitive dairy cows, you’ll see why they call it the Garden State. The farm is nestled into the Sourland Mountain ridge in Western New Jersey and feels light-years away from the state’s congested suburbs.

About 360 acres of Fulper’s farm have been preserved with public money used to keep the land free from development for generations to come.

Several feet below some of his fields are two pipelines. They were laid during World War II to move crude oil from the Gulf Coast up to the Northeast, decades before these tracts were preserved.

Today, these pipelines move natural gas.

In the summer, when the weather is hot and dry, Fulper said he can see the results of the extra heat the pipelines throw off.

“The corn over top of these pipelines was withered up and basically yielded very low yields in this area,” he said, stretching his arms out to show where the brown strips of dried corn stretched across the field last summer.

When Fulper first got a letter that another pipeline company wanted to cross through his land, he shrugged it off.

“They can’t cross my farm now – it’s preserved,” he thought to himself.

But soon, Fulper learned that pipelines are allowed through preserved lands and he worried this new pipeline could ruin more of his crops.

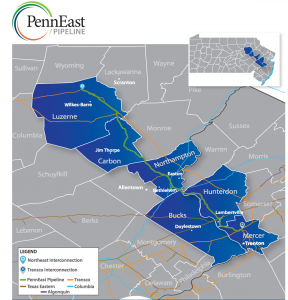

The proposed PennEast pipeline would travel 114 miles from Luzerne County in Northeast Pennsylvania to hook up with other major pipelines near Trenton.

“I’m not naïve to the fact that hey – we need to move energy, we need to have our own energy. It’s a good thing,” he said. “Obviously, whenever you put a pipeline in next to somebody’s property, it’s tough for them, so they’re the losers.”

“If you’re gonna burn a fossil fuel, natural gas is the one to burn”

So who are the winners?

Recently, PennEast backers gathered New Jersey businesspeople in a hotel ballroom in Trenton to make their case for the pipeline.

Opposition to the project has been strongest in New Jersey. But New Jersey customers stand to benefit the most, according to Pete Terranova who heads up the consortium of companies behind the pipeline – including five local gas and electric utilities.

Here’s Terranova’s pitch:

The pipeline would supply some power plants in the region with natural gas, which releases less carbon dioxide than burning coal.

It would also give local utilities enough gas to keep prices down during cold winter months when demand is highest and to help more customers switch from more expensive heating oil. That includes some towns along the pipeline’s path that currently do not receive natural gas service.

Getting that gas straight from the Marcellus Shale via pipeline, Terranova says, is good not only for his bottom line, but also his customers and the environment.

“If you’re gonna burn a fossil fuel, natural gas is the one to burn – it’s not coal, it’s not oil, it’s natural gas and the price is very competitive which is why people want it,” he said. “So I think that it’s up to us to get that natural gas from the closest place you can produce it to the markets that are very nearby because the cost will come down.”

“Do you need all these pipelines?”

Katherine Dresdner and Patty Cronheim aren’t buying it.

Like the farmer, Rob Fulper, they don’t think pipeline companies should be allowed to cut through farms, parks and other areas that have been protected from development through state and local bond issues.

Dresdner is an attorney for a citizens group in Hopewell Township, New Jersey that is mulling a lawsuit against PennEast to keep the pipeline off preserved lands.

“It’s a violation of the easements and the covenants that preserved those lands,” she said.

A local land trust estimates the PennEast pipeline will cut through more than $37 million worth of preserved open space.

The tradeoff isn’t worth it to Cronheim. She’s also concerned that the pipeline will cross right under the Delaware River and some of the state’s cleanest streams.

Cronheim thinks the real plan is to sell that gas for a higher price in countries like India and Japan.

“Someone’s going to be paying for these pipelines,” she said, “Not just the PennEast pipeline, but all of these pipelines together and a lot of this gas is going to be going overseas.”

The possibility of natural gas exports have become a key talking point for environmental groups fighting this and other proposed pipelines who want to raise suspicion that companies like PennEast are not being truthful about their intentions.

Sami Yahya, an analyst with Bentek Energy, says it is unlikely that any of the gas that would flow through PennEast would be destined for export since the pipeline is backed by local utility companies looking for more efficient access to the Marcellus Shale.

“Here’s the tricky part: is this gas needed? Do you need all these pipelines? Not really,” Yahya said.

The East Coast is experiencing a pipeline-building boom. PennEast is one of at least six other pipeline projects proposed for New Jersey alone as drillers push to get their gas to markets as far as New England where prices spike during times of high demand.

However, Yahya is concerned that the rush to build new pipelines will eventually lead to what he calls an “oversupply situation.”

“It’s kind of like someone blew a whistle, they need some help and we have the rest of the world trying to help them,” he said.

KATIE COLANERI/STATEIMPACT PENNSYLVANIA

The new route of the PennEast pipeline would cross Angele Switzler’s farm in Delaware Township, New Jersey. The company wants to site the pipeline along the power lines that border her property.

“I would like to be reassured that it is for the greater good”

Since the pipeline was proposed last August, PennEast has changed the proposed route to run at least halfway along existing utility lines and avoid some preserved lands.

That change spared Rob Fulper’s farm.

“I’m relieved that they’re looking at another potential site, but now I realize there’s other landowners that are now in the path of this pipeline,” he said, “I just don’t want to feel like I pushed a problem to somebody else.”

Somebody else like Angele Switzler, who got a letter just before Christmas that PennEast now plans to build the pipeline on a new easement next to the power lines that run along the edge of her farm in Delaware Township, New Jersey, which is not preserved.

Switzler has no problem with the power lines – a large solar array on her property is connected to the electrical grid.

“So I know that’s benefitting our community,” she said.

She doesn’t feel that way about the pipeline.

“I would like to be reassured that it is for the greater good because it doesn’t seem like it,” she said. “This is just something that’s driven by economics of a big corporation, not need.”

The Federal Energy Regulatory Agency or FERC will ultimately decide whether sacrificing that open space is worth the promise of cheap gas. PennEast plans to submit an application to FERC this summer in hopes of putting the pipeline in service in 2017.

Many landowners are struggling with the costs and benefits of letting a pipeline company onto their property.

If FERC approves the PennEast pipeline, they can negotiate a one-time fee for the use of her land – possibly in the hundreds, maybe thousands of dollars.

But Switzler, who will be able to watch the construction from the floor-to-ceiling windows in her living room, points to the five huge blue spruce trees she and her husband planted when her son was born 21 years ago. If the PennEast pipeline is built, they’ll probably have to be cut down.

She doesn’t think it’ll be worth the sacrifice.