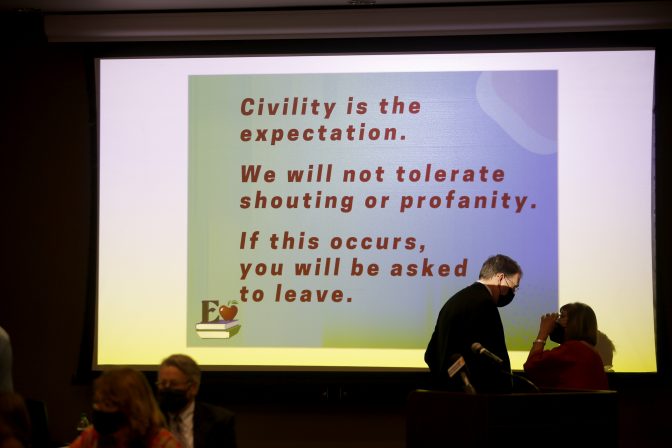

Those opposed to the Edmond Public Schools mask requirement cheer after a public comment during a public a school board meeting in Edmond, Okla., Thursday, Sept. 9, 2021.

File photo / Courtesy The Oklahoman

Those opposed to the Edmond Public Schools mask requirement cheer after a public comment during a public a school board meeting in Edmond, Okla., Thursday, Sept. 9, 2021.

File photo / Courtesy The Oklahoman

The Jenks Board of Education had enough of the woman with the small dog.

The meeting room was full to the brim and thick with tension as the school board decided Sept. 9 whether to require masks in the district south of Tulsa.

In a crowd packed with residents opposed to a mask mandate, no one’s jeers rang louder than those from a woman holding a Papillon in her arms. Finally, the board had security escort her out of the building.

“Every one of you, shame on you,” the woman yelled. “You guys make me sick.”

As discourse rages nationwide over a lack of civility in school board meetings, Oklahoma school board members say the criticism they face has been noticeably more intense since the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Absolutely the dial has turned up,” Jenks board Vice President Melissa Abdo said. “I mean, the dial is elevated for sure.”

And though no board members The Oklahoman and StateImpact Oklahoma interviewed recall any threats to their physical safety, unlike in other parts of the country, they reported more contentious and less constructive dialogue in their public proceedings.

School boards across the state have faced angry crowds eager to shout down mask mandates, quarantine policies, and political issues that percolated down from the state and national level.

In Tahlequah, a vote on a school mask requirement was met with a chorus of angry heckling. In Edmond, a local mother said the school board pushed Marxist views, as supporters cheered from their seats. In Stillwater, six parents took their school district to court over distance learning.

“It’s been a no-win for at least a year and half,” Tahlequah board member Chrissi Nimmo said.

In Jenks, the woman with a Papillon balanced on her hip marched out of the board meeting chanting “shame on you” with a taunting cadence often heard on a school playground.

The dog gave a flick of its tail as its owner exited to a round of applause.

To this day, the Jenks school board is unsure where the woman came from or whether she has children enrolled in the school district, Abdo said. The board members, who unanimously voted in favor of a mask requirement, never heard from her again.

“We want people to come to our board meetings,” Abdo said. “We want that engagement, even knowing that not everybody’s going to agree with our individual decisions.

“But you know, if you’re rude or disruptive and you’re disrespecting other people who are speaking, then no matter what your opinion is, you’re going to be asked to leave.”

File photo / Courtesy The Oklahoman

People wait for the start of a school board meeting for Edmond Public Schools, Thursday, Sept. 9, 2021.

During the Oklahoma Legislature’s 2021 session, lawmakers broadened the state’s ability to file misdemeanor charges for interfering in public meetings.

It’s unlikely anyone has been charged under the broadened statute for disrupting state business, according to an analysis of online court records by Oklahoma Policy Institute Research Director Ryan Gentzler. The three defendants charged with “disrupting state business” this year were not accused of interrupting public meetings.

However, some board officials say they’ve noticed concerning behavior by a rare few.

Stillwater school board member Marshall Baker said some meetings in his district became so tense that he was relieved security officers were in the room.

“There have been times where I’ve looked twice before I left the board meeting at nine o’clock at night,” he said. “There have been things said on social media that made me wonder, ‘Is that a threat I should legitimately worry about?’”

Baker served a term on the Stillwater school board before the COVID-19 pandemic. He left to pursue a job in another state and quickly returned. Once his family moved back to Oklahoma, he decided to run again, but since the COVID-19 outbreak, his experience has been different.

“The first time I served on the board, it really was fun; it was celebrating kids,” Baker said. “This time it’s not fun, but it’s much more important. I would say that’s the biggest difference that I’ve seen. It really feels like service.”

Baker chalks up most of the negative behavior to some being “rationally irrational,” a byproduct of both a divided nation and the deep concern parents have for their children’s education.

Most topics that set his community on edge involved COVID-19 precautions, like virtual schooling, mask requirements and vaccinations.

But, political issues also created tension. Baker said school board discussions have strayed from student growth and academic outcomes to national talking points like critical race theory — a college-level academic concept on systemic racism that’s not usually taught in K-12 schools.

More ideological arguments like these have trickled down to the local level, said Shawn Hime, executive director of the Oklahoma State School Boards Association.

“I think we have more political issues from society that are entering the school board room,” Hime said. “Masks or no masks, vaccines or no vaccines, and other social issues that are now at the front steps of the school.”

When these national controversies, which Baker called “flavors of the day,” reach the local level, it falls on school board members to address them, drawing ire and passion from their communities.

For example, the state Legislature forbade the teaching of certain race and gender topics through House Bill 1775 this year. School boards were then compelled to enact the legislation within their districts.

“When they get to our bench, we have to put them in practice, and that’s challenging,” Baker said.

An already politically charged discourse surrounding school boards reached a fever pitch on Sept. 29 when the National School Boards Association complained of threats against school board members and requested federal intervention from the Biden Administration.

U.S. Attorney General Merrick Garland then ordered the FBI and federal prosecutors to meet with local law enforcement across the country to discuss the “disturbing trend” of harassment and intimidation against school board members.

Seventeen state attorneys general, including Oklahoma’s John O’Connor, said federal involvement would chill lawful dissent from parents.

“Parents have rights under the First Amendment, and our school boards should solicit and welcome parental input,” O’Connor said in an Oct. 18 statement. “Our schools will be better educators if they will listen to the parents.”

The NSBA has since apologized for its Sept. 29 letter, saying there was “no justification” for some of its language, but not before multiple state school board associations cut ties with the national affiliate.

Oklahoma’s school boards group didn’t split from the NSBA, but Hime, the executive director, said he made his objections to the letter known. Any threats against a school board should be handled locally, not by federal officials, he said.

Despite school board meetings turning toxic nationwide, Hime said Oklahoma board members strive for open communication with their communities.

“It’s not wrong to have disagreements on what’s best for our children,” Hime said. “We just always try to remember to disagree with compassion and respect other people’s opinions and then move forward with what’s best for the group.”

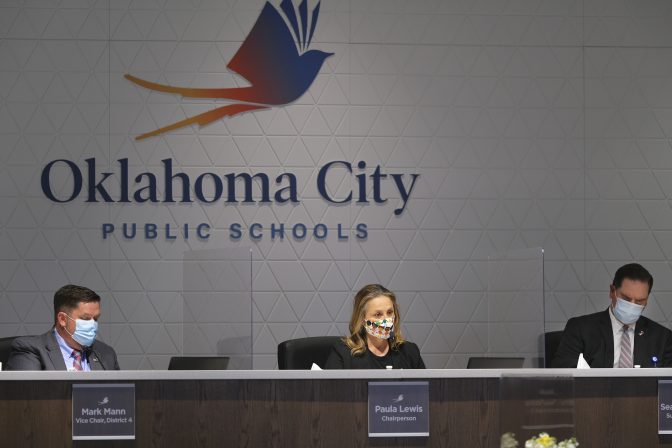

File photo / Courtesy The Oklahoman

Mark Mann, Paula Lewis and Sean McDaniel during the Oklahoma City Public School Board meeting Monday, April 12, 2021.

The very nature of elected school boards involves a certain level of politicking.

But it’s “regrettable” that national talking points, like critical race theory, are considered educational issues, Abdo said.

The complaints Abdo heard from parents pre-COVID – day-to-day concerns going on in schools – have given way to ideological debates.

Abdo said she hopes future school board candidates don’t run for office because of political trends.

A focus on politics rather than students’ needs could be a concern for future elections, Oklahoma City Board of Education Chair Paula Lewis said.

“If you had a big push of money and financing come in and you could switch the nature of our board, you could really undo things that we’ve really worked hard to get accomplished for kids,” Lewis said. “I do worry about that because contentious board meetings are disruptive to people’s belief in their district.”

Instead, Abdo said, she wants her fellow school board members to keep the children they’re supposed to serve in mind as they make decisions. Luckily, many of those who she knows in Oklahoma are doing just that.

“It’s the people who are there for the right reasons, and that’s exactly who you want to be there,” she said.

This story is a collaboration between The Oklahoman and StateImpact Oklahoma.