About 82,000 children in Oklahoma lack health insurance, ranking the state 48th in the nation.

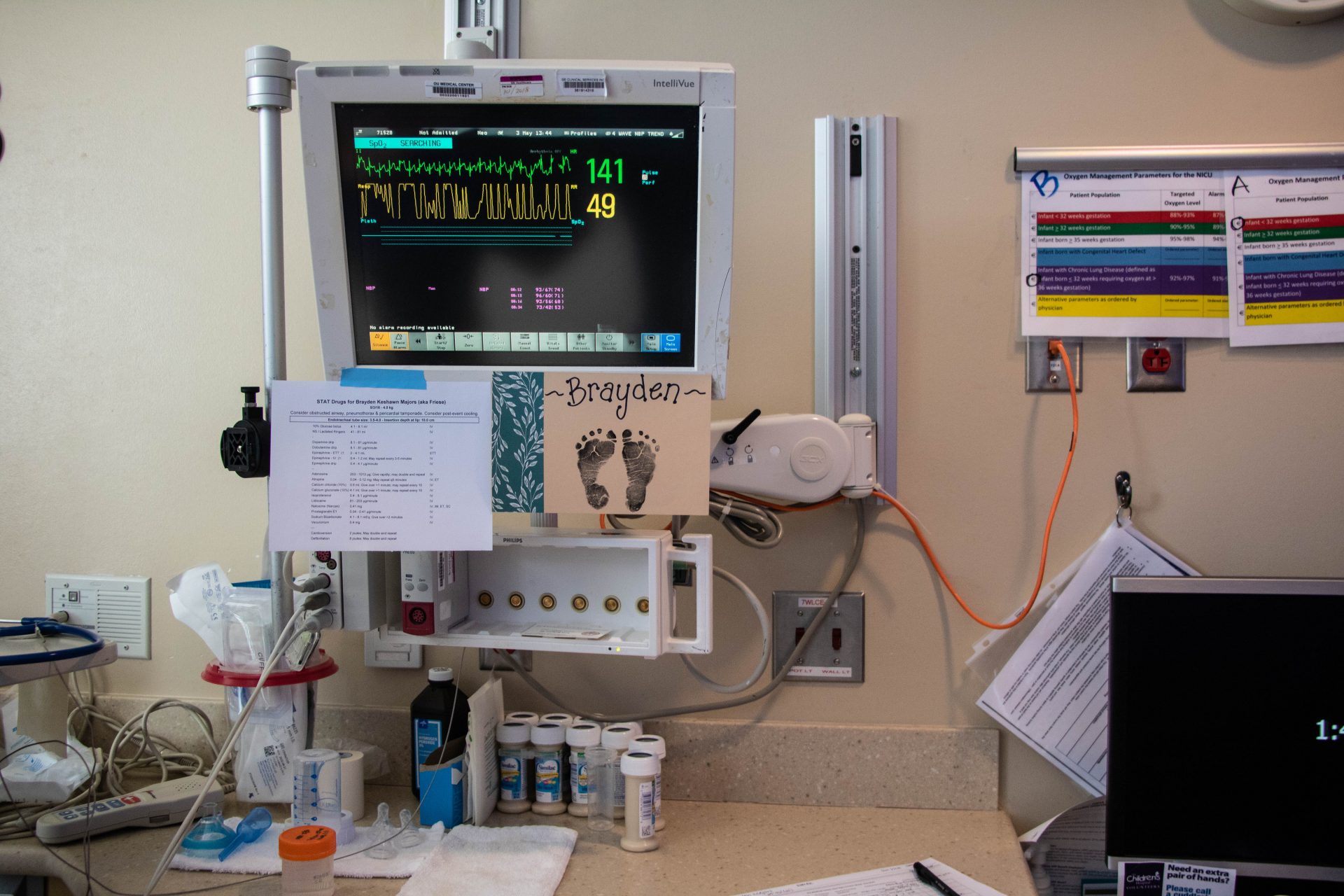

Jackie Fortier / StateImpact Oklahoma

About 82,000 children in Oklahoma lack health insurance, ranking the state 48th in the nation.

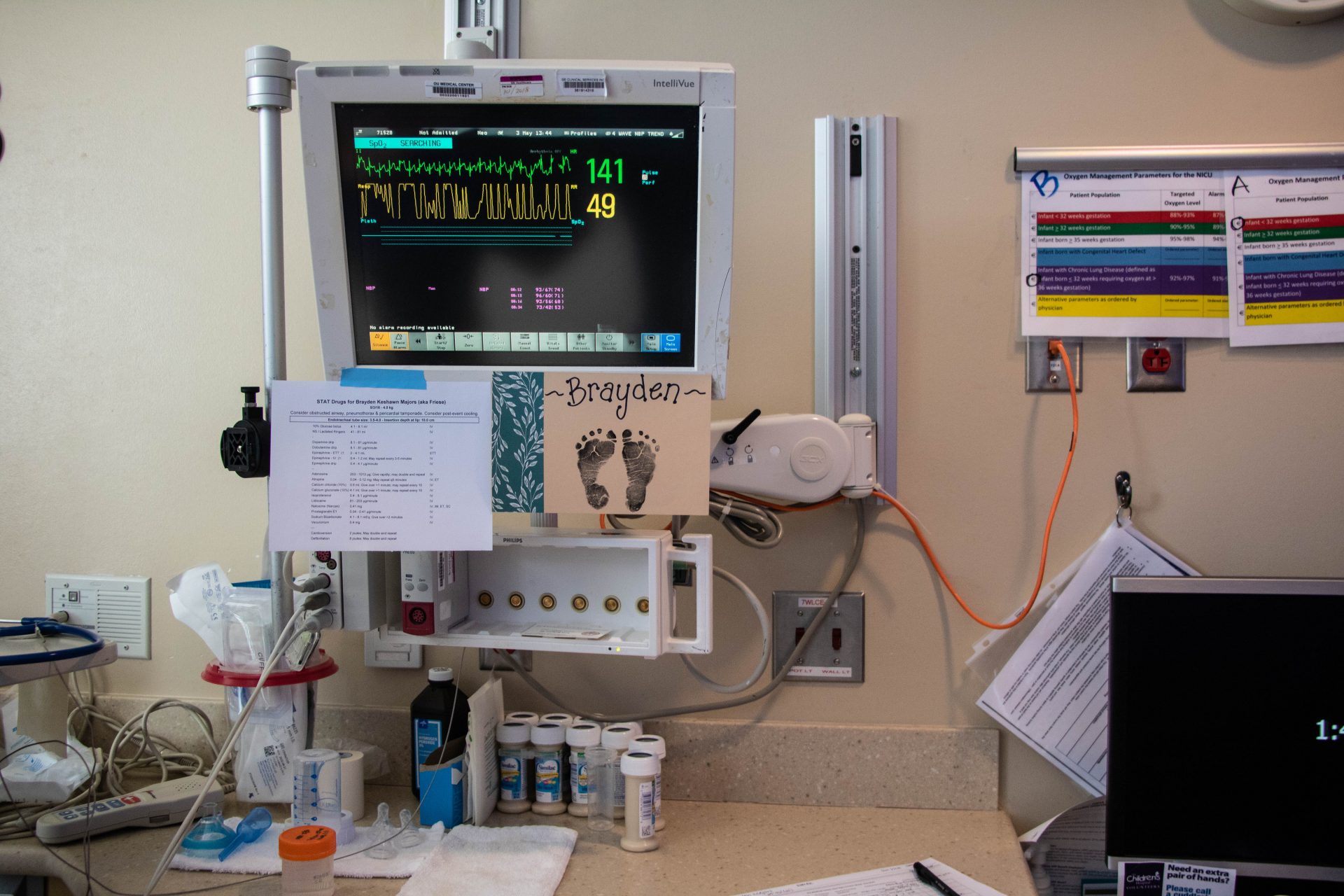

Jackie Fortier / StateImpact Oklahoma

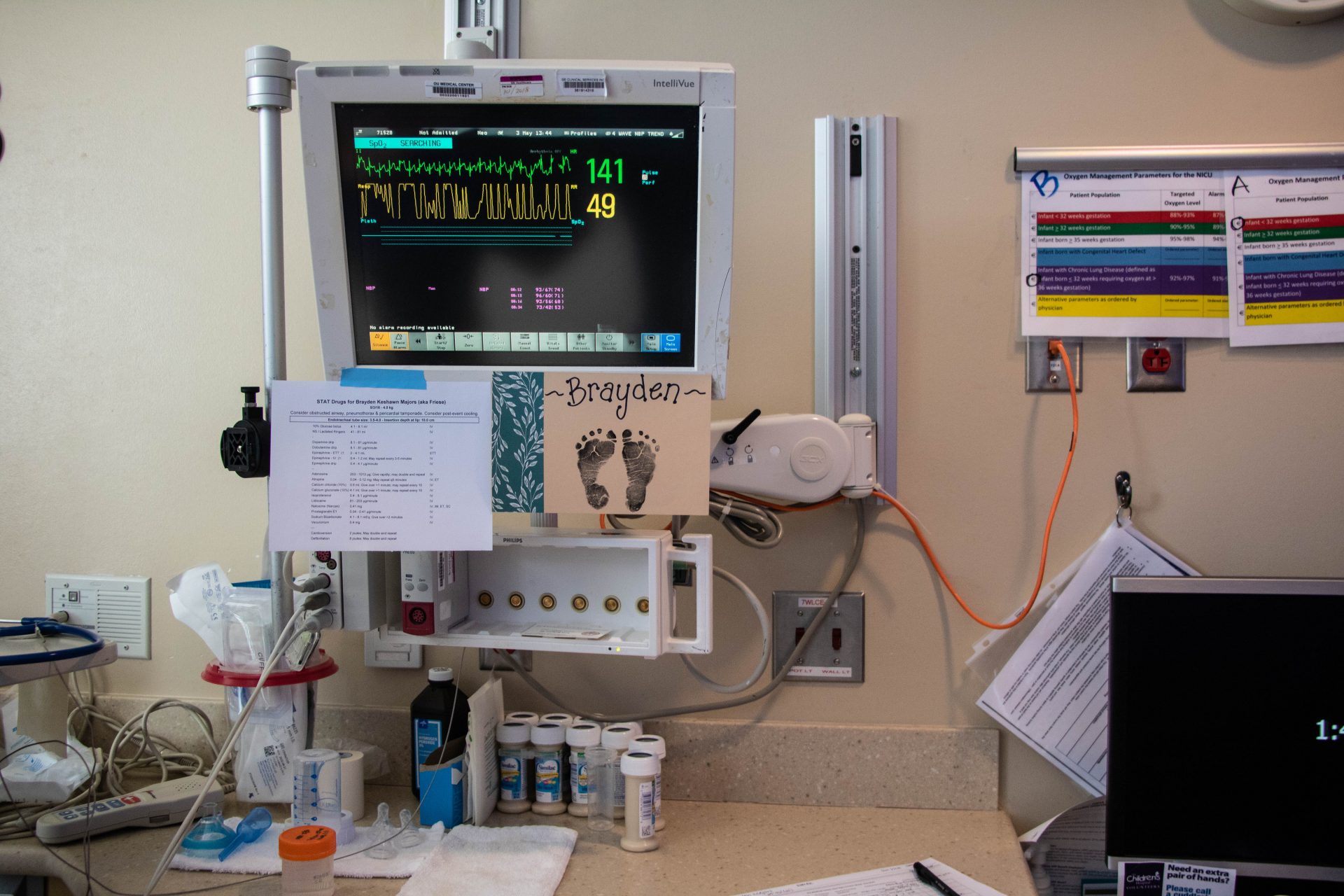

Jackie Fortier / StateImpact Oklahoma

About 82,000 children in Oklahoma lack health insurance, ranking the state 48th in the nation.

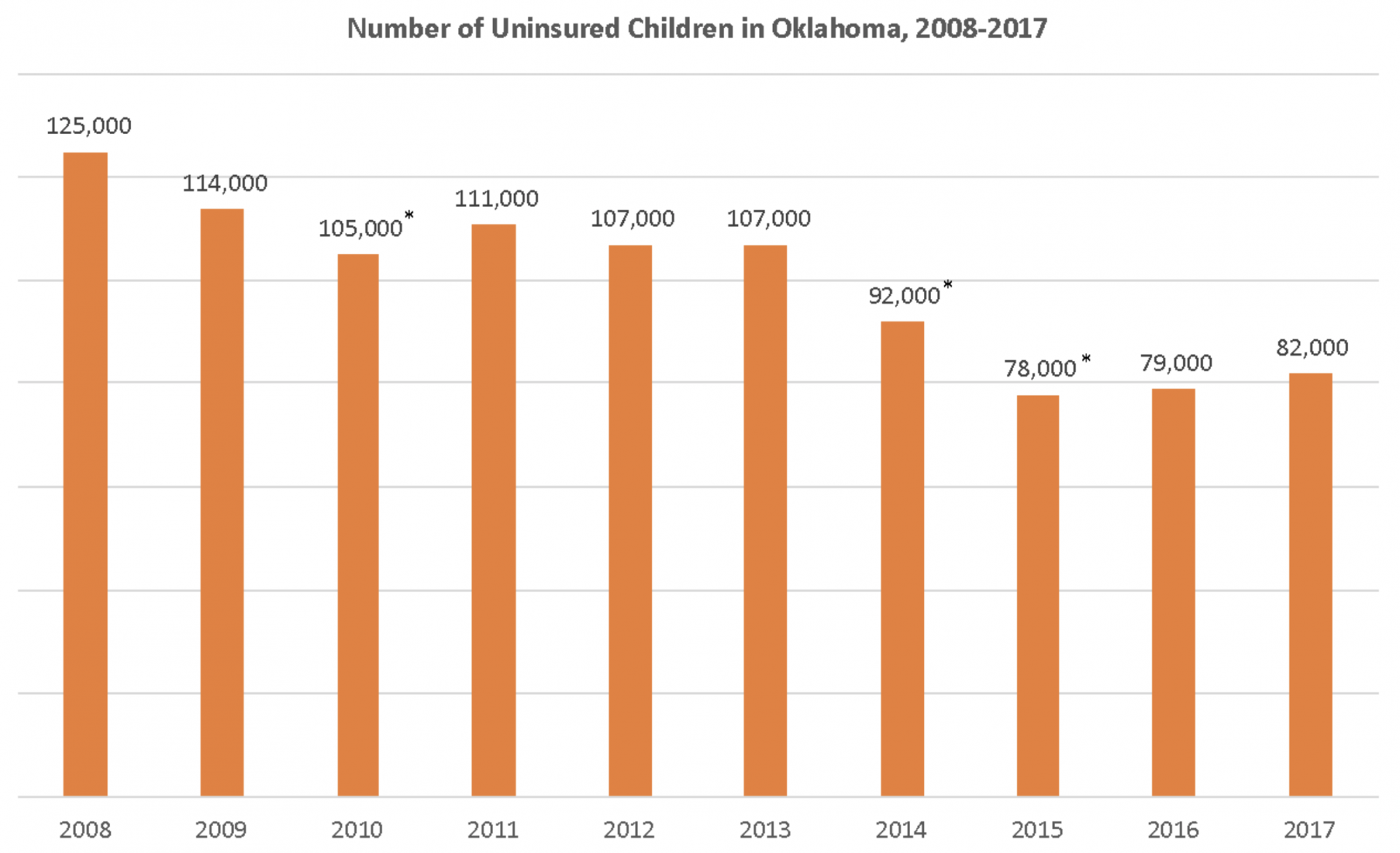

After a decade of improvement, a new study suggests the rate of uninsured children is increasing in Oklahoma.

Research from the Georgetown University Center for Children and Family Studies shows the state’s rate of uninsured children increased to 8.1 percent in 2017 from 7.7 percent in 2016, an amount that dropped Oklahoma to 48th in the nation.

Overall, researchers found that the number of uninsured children nationwide ticked up from 4.7 percent – a historic low – to 5 percent during the same period.

Georgetown researchers examined newly released U.S. Census data and found that three-quarters of children nationwide who lost health insurance coverage live in states like Oklahoma that have not expanded Medicaid to parents or other low-income adults.

To date, 37 states including Washington, D.C., have adopted the Medicaid expansion; Fourteen other states, including Oklahoma, have not adopted expansion.

Rates of uninsured children in non-expansion states increased at nearly triple the rates recorded in states that expanded Medicaid, researchers found.

The drop occurred during a period marked by a strong national economy and low unemployment rates, so researchers attribute the decline to changes in federal immigration policy and the Affordable Care Act, known as Obamacare.

Lead researcher Joan Alker said the Trump administration’s cuts to outreach and enrollment grants for health insurance marketplaces combined with a shorter window of time people have to sign up likely “intimidated” many parents whose children may be eligible.

“A quarter of all children living in the United States has a parent who is an immigrant,” Alker said on a press call about the new research. “For these mixed-status families, there is likely a fear of interacting with the government, and this may be deterring them from signing their children up for government-sponsored healthcare.”

The data show the percentage of Oklahoma’s children receiving employer-sponsored health insurance through their parents ticked down slightly, to 38.8 in 2017 from 39.3 percent in 2016. While it’s not statistically significant, researchers found small drops in coverage across the board.

There was a slight decrease in enrollment in government-sponsored health insurance programs like Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program known as CHIP, and in children getting coverage through the individual marketplace created by the Affordable Care Act.

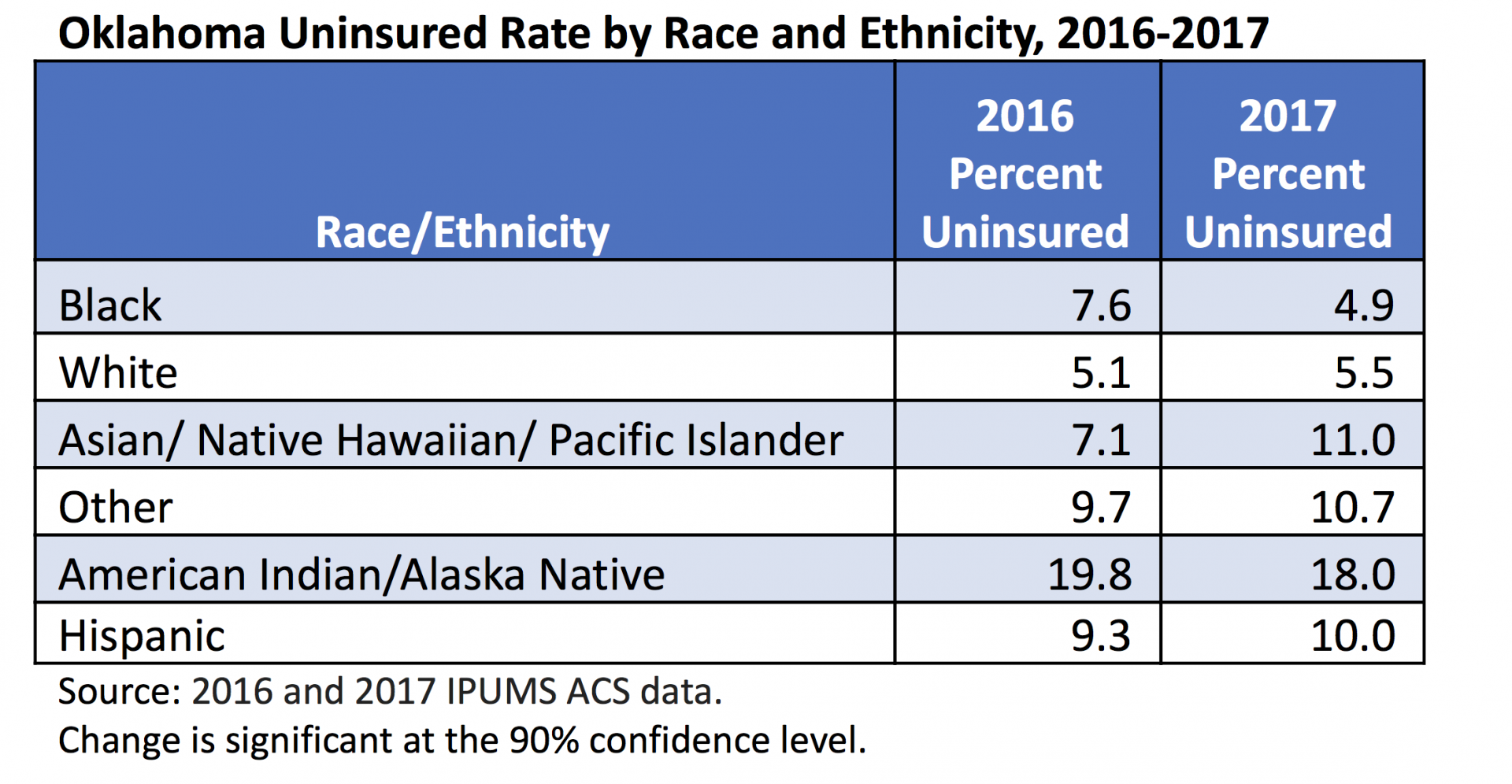

When the data are broken down by race and ethnicity, Native American and Alaskan Native children showed the highest uninsured rates nationally and in Oklahoma. Alker said many people are confused by the role of the Indian Health Service, which the U.S. Census Bureau does not count as health insurance.

“The IHS is not a health insurance program; it’s a provider,” Alker said. “While some of these children may be getting services from the IHS, that’s not the same thing as having insurance. If they have to get services outside of IHS, they will incur costs, and that’s what insurance is about, it protects families from medical costs.”

Health insurance rates for black children in Oklahoma improved 2.7 percent from 2016 to 2017, while rates for Asian, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander children worsened by 3.9 percent, the data show.

“We’re seeing clustering in really two groups, one is states that have not expanded Medicaid to parents and other adults, and the second is states that have large populations of Native American and Alaskan Native populations,” Alker said.

Alker expects more children to lose health insurance coverage if another proposal takes effect.

Earlier this year, the Trump administration began pursuing rule changes that would make it harder for immigrants to get a visa if the federal government determines they’re likely to use certain public benefits, including health, nutrition and other non-cash programs.

The proposal is open for public comment until Dec. 10.

Alker and other experts think the proposed rules are likely to cause a chilling effect; immigrant families could drop out of programs like Medicaid, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program and other initiatives fearing it could negatively impact their legal status, even if their children are citizens.

“The the majority of uninsured children are eligible for Medicaid or CHIP but aren’t currently enrolled,” Alker said.

U.S. Census Bureau

Change is significant at the 90% confidence level. Significance is relative to the prior year. The Census began collecting ACS data for the health insurance series in 2008, therefore there is no statistical significance available for 2008.

Oklahoma already has the second-highest uninsured rate in the country — more than 14 percent of adults in Oklahoma don’t have health insurance.

If Oklahoma’s application for a Medicaid waiver to impose a work requirement on very low-income adults, including parents who receive health coverage through Medicaid, is approved, Alker expects the child uninsured health rate also to increase.

Under the proposal, able-bodied adult beneficiaries would have to document that they are working at least 20 hours a week or participating in job-training or volunteer activities to maintain their SoonerCare coverage.

If it’s approved, Oklahoma would be the only non-expansion state to have work requirements.