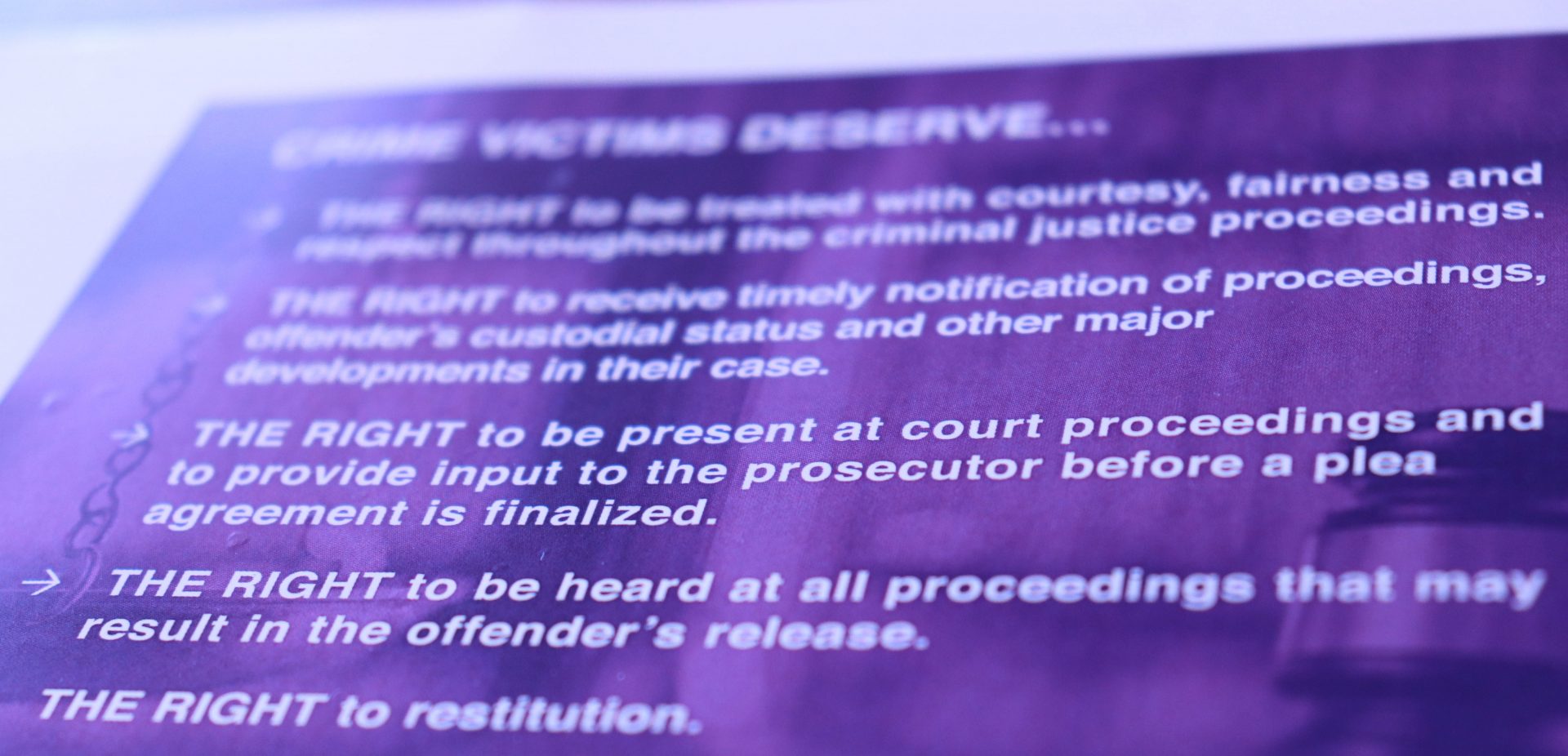

A Marsy's Law for Oklahoma handout.

Quinton Chandler / StateImpact Oklahoma

A Marsy's Law for Oklahoma handout.

Quinton Chandler / StateImpact Oklahoma

Quinton Chandler / StateImpact Oklahoma

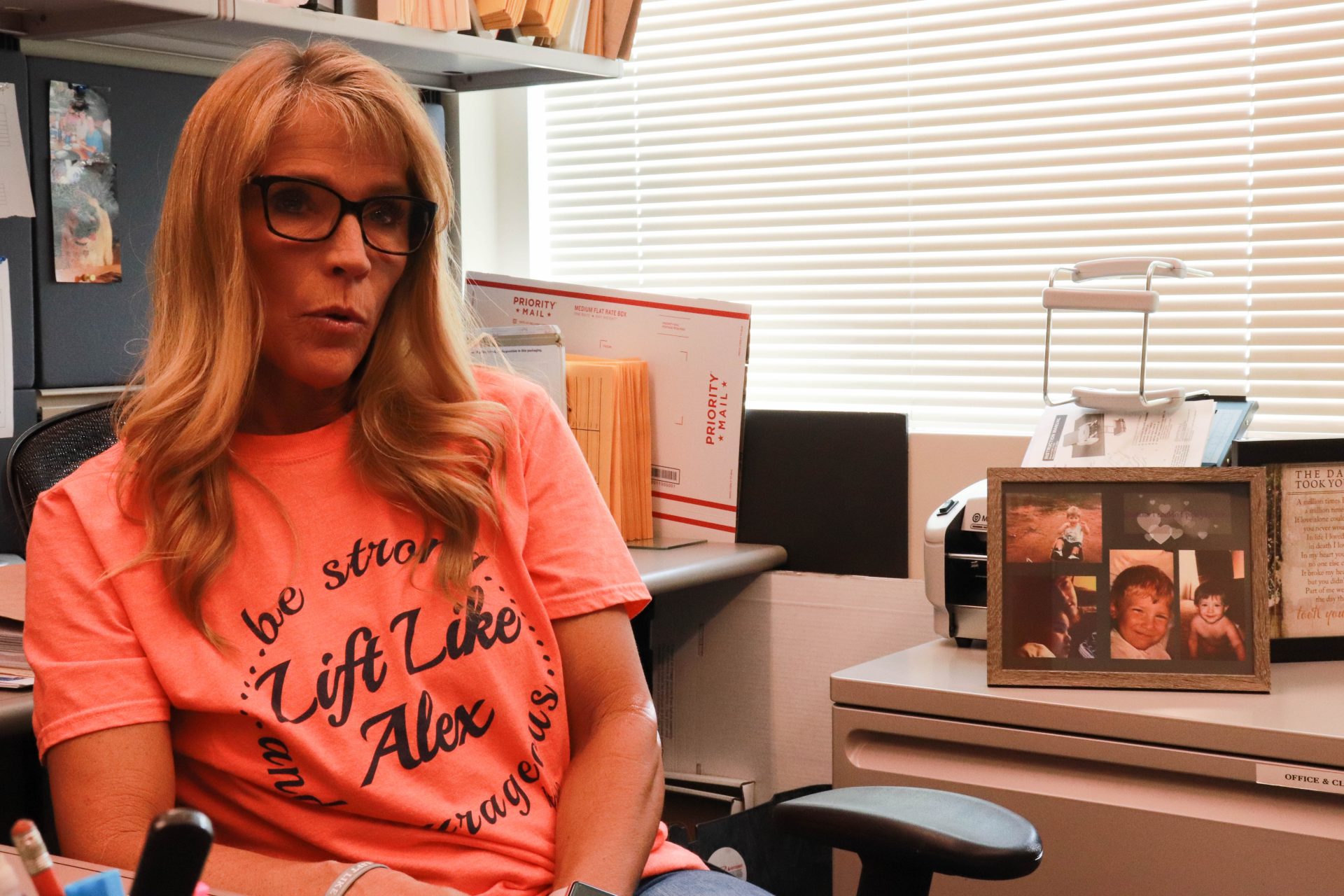

Kelly Vierling said her family found out quickly it was their responsibility to figure out what would happen next during the prosecution of her son’s killer.

Kelly Vierling said her son had a “huge heart.”

Vierling’s eyes watered as she described her 21-year-old son Alex in her office on the Oklahoma State University campus.

Alex was killed in Stillwater in 2014.

Vierling said her son carried a gun to protect himself. He had it with him when he went to a friend’s party the day he died.

Alex showed the gun to several people, according to court records. An 18-year-old woman took the gun and pointed it at Alex. She told police she didn’t think it was a real gun, and recalled hearing a loud pop and seeing Alex lean over. She told police she didn’t remember pulling the trigger.

The woman was convicted of second-degree manslaughter. After the shooting, Kelly Vierling said she was left in the dark for a month.

“We assumed there would be charges pressed. Nothing was happening,” Vierling said.

State Question 794, which would give crime victims new rights under the state constitution, goes before voters on Nov. 6. Oklahoma already has a bill of rights for crime victims that includes many of the provisions the ballot initiative provides, but advocates like Vierling say the changes will help future crime victims navigate a confusing criminal justice system.

After her son’s death, Vierling said no one kept her family updated on police actions and the months of court dates that followed. She said no one told her family when a warrant was issued for the shooter, or when the shooter was arrested and released on bond.

“If you want to know what the next court date is, you better be at the one prior,” Vierling said.

Vierling is still upset about a twist to the shooter’s 8-month sentence. She said no one from the state told her that the shooter received a special status that cut the sentence in half. The shooter was scheduled for release three weeks after Vierling discovered the change.

“Is it too much to ask to know that a warrant has been issued,” Vierling asked. “Is it too much to ask to sit in a bond hearing?”

If voters approve SQ 794, Vierling thinks other victims and families won’t run into the same problems.

The ballot initiative is part of a national campaign called Marsy’s Law, which has convinced six states to change state constitutions to give victims and their families constitutional rights similar to criminal defendants. Montana courts repealed Marsy’s Law late last year because it conflicted with the state constitution.

Erin Sheley, a professor at the University of Oklahoma’s College of Law, said SQ 794 would have a limited effect on criminal law in Oklahoma. Oklahoma already has a detailed list of rights for crime victims, which includes a requirement that victims and families are informed about important court dates.

Tulsa County Public Defender Corbin Brewster said SQ 794 would damage Oklahoma’s court system.

Brewster doesn’t like that SQ 794 requires crime victims be given a voice at important parts of a trial, like a defendant’s bond and plea hearing. He said victims have a different set of interests than prosecutors and defense attorneys. Brewster worries victims could block plea agreements, which are used to settle most felony cases.

Sheley doesn’t think that victims speaking at these hearings will disrupt most criminal trials, but she said it could slow down and add costs to Oklahoma’s already inefficient court system.

“I am not a fan of having this at every single part of the process,” Sheley said. “Whenever the criminal justice system costs money and time, usually criminal defendants suffer.”

Sheley said victims should have a voice at sentencing and later parole hearings, which state law currently allows.

Brewster is also afraid SQ 794 will complicate trials if attorneys try to interview victims and families, or ask them to produce evidence.

Sheley doubts that would be a problem.

“Maybe the victim wouldn’t have to respond directly to requests for things, but the prosecution will always have to,” Sheley said, adding that judges would still be able to order victims to cooperate.

Another concern, Brewster said, is that SQ 794 could allow victims, their families or attorneys to disrupt trials by demanding the court enforce their rights.

Sheley is sympathetic. She said disruptions are possible, but argued there are times when courts should hear from victims and families, like when a defendant could be released on bond.

“The victim does have something to say about the ongoing dangerousness of the accused,” Sheley said.

Sheley said her biggest concern is that SQ 794 attempts to make crime victims’ rights equal to the defendants’ in court. She said defendants’ rights stem from the U.S. Constitution and she’s wary of creating situations where victims’ rights could be pitted against defendants’ rights in court.

“That’s inviting some problems,” Sheley said.

Sheley does not think SQ 794 will directly challenge defendants’ constitutional rights. If a judge embraced state law over federal law, Sheley said the decision would be quickly addressed in federal court.

Kelly Vierling glances at framed pictures of her son that she keeps on a file cabinet behind her desk. At the very least, she said SQ 794 would guarantee crime victims and their families have access to the information they need.

She said the state question is a crucial and necessary step toward helping people like her.

“Knowledge is power for a victim,” she said.