A field medic raises her fist as protestors stand near a fire blocking a road along the Dakota Access Pipeline Route near the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in North Dakota.

Avery White / Oceti Sakowin Camp/CC BY-NC 2.0

A field medic raises her fist as protestors stand near a fire blocking a road along the Dakota Access Pipeline Route near the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in North Dakota.

Avery White / Oceti Sakowin Camp/CC BY-NC 2.0

Avery White / Oceti Sakowin Camp/CC BY-NC 2.0

A field medic raises her fist as protestors stand near a fire blocking a road along the Dakota Access Pipeline Route near the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in North Dakota.

Oklahoma legislators are advancing a bill that outlaws trespassing on sites containing “critical infrastructure.” Supporters say the measure will help prevent damage and disruption of energy markets, electric grids and water services, but environmental activists and civil rights groups say the bill’s real purpose is to block political protests of pipelines and similar projects.

Casey Camp-Horinek was standing and singing when police officers in riot gear and armored vehicles moved in to remove protesters camped along the Dakota Access Pipeline route near the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in North Dakota.

“Planes, snipers, sound cannons, percussion grenades, mace, pepper spray, tasers,” she says. “It was a scene out of a science fiction movie.”

As a leader of the Ponca Tribe, headquartered near Ponca City, Camp-Horinek traveled to North Dakota to deliver a resolution on behalf of her tribe: The Ponca supported the Standing Rock Sioux in opposing the federal government’s approval of the 1,200-mile pipeline designed to carry hundreds of thousands of barrels of crude daily from Canada’s Bakken Shale to refineries in Illinois.

The tribes argued the government didn’t properly assess the risk the pipeline posed to water, wildlife and the environment when it issued permits. On Oct. 27, 2016, Camp-Horinek was arrested.

“I did not have a choice there,” she says. Police marked a number on her arm, Camp-Horinek says, and the arms of more than 140 other people arrested “as if we were going to be taken to the concentration camps.”

Camp-Horinek is due back in a North Dakota courtroom this summer on misdemeanor nuisance charges. Legislation under consideration at the Oklahoma capitol could make such protests on land owned by energy companies a felony with $10,000 fines.

The Oklahoma House on Tuesday voted 70-24 to approve House Bill 1123, legislation that outlaws trespassing on “critical infrastructure.” The principal author, Scott Biggs, R-Chickasha, did not respond to interview requests. In debate on the House floor, Biggs said the measure is not intended to prevent peaceful political protests. The point, he said, is to discourage disruptive, damaging ones like Standing Rock.

“Across the country, we’ve seen time and time again these protests that have turned violent, these protests that have disrupted the infrastructure in those other states,” he said. “This is a preventative measure … to make sure that doesn’t happen here.”

Oklahoma is not currently experiencing crowded, high-profile protests, but Biggs says the state has a lot of infrastructure that disruptive activists could target — from dams, water treatment and chemical plants, to oil and gas hubs, petroleum refineries and storage facilities.

“There are a lot of things in Oklahoma right now that are drawing the attention of bad actors,” he said on the House floor.

Trespassing is already illegal in Oklahoma. In its current form, HB 1123 creates three new classes of the crime and assigns minimum penalties for people trespassing on a dozen types of critical infrastructure. The classes range from a misdemeanor, to felonies for people who damage or inhibit operations — or intend to. The minimum fines range from $1,000 to $100,000.

The bill also adds steeper penalties for groups found to have conspired with trespassers that damage or tamper with critical infrastructure, though the state already has anti-conspiracy laws on the books. Those minimum fines levied on critical infrastructure conspirators could be as high as $1 million.

In debate on the House floor, lawmakers from both parties questioned whether new classes of trespassing and conspiracy crimes were needed, and what kind of organizations and entities might be considered trespassing conspirators. Could tribes be fined for buying plane tickets for members arrested for damaging critical infrastructure during a protest?

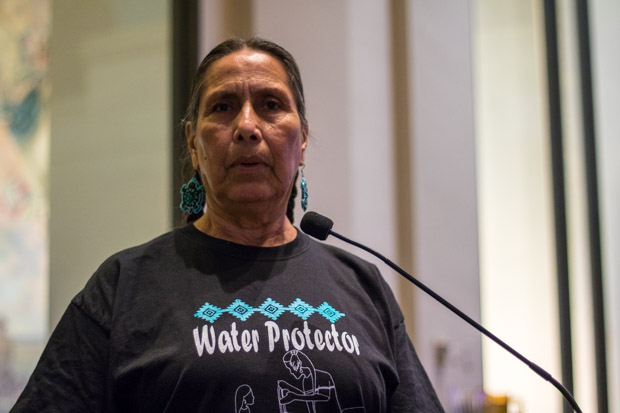

Joe Wertz / StateImpact Oklahoma

Casey Camp-Horinek, speaks out about earthquakes and injection laws at a hearing at the Oklahoma Capitol in October 2016.

University of Michigan professor Michael Heaney, who studies political protests, says state governments have historically crafted new legal tools in the wake of public protests.

“Authorities have never liked groups of people getting together in public spaces and contesting what the authorities want,” he says.

Heaney says law enforcement agencies and local governments are having a hard time responding to the scale and speed of protests organized on social media.

“Being able to create really disruptive protests has gotten easier,” he says.

Oklahoma is one of more than a dozen other Republican-led states considering new laws that could limit mass protests. Some lawmakers say legislation is needed to battle a scourge of professional protesters organized by wealthy liberal activists — an argument magnified by President Trump, though little evidence supports this claim.

Attorneys and civil rights groups like the Oklahoma chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union say HB 1123 could criminalize political protest and block free speech.

Camp-Horinek with the Ponca Tribe is convinced the Oklahoma bill was written with the oil and gas industry in mind, despite reassurance from Rep. Biggs that it is not anti-protest and only applies to critical infrastructure.

“There’s no doubt that this is a knee-jerk reaction to what went on in Standing Rock,” she says.

Camp-Horinek says steep fines, penalties and a greater likelihood of arrest won’t deter her and other tribal activists, who will continue fighting for the environment and their people.

“I don’t think we can go through life living in fear of a man-made law,” she says.