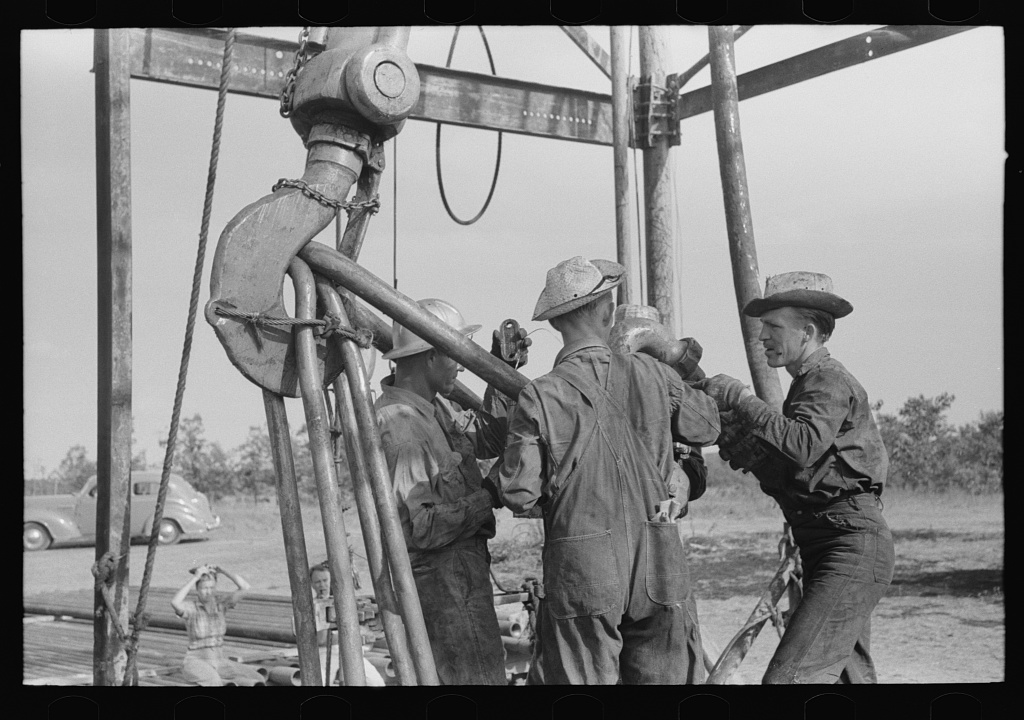

Workers in an oil field near Seminole, Okla., in 1939.

Russell Lee / Library of Congress

Workers in an oil field near Seminole, Okla., in 1939.

Russell Lee / Library of Congress

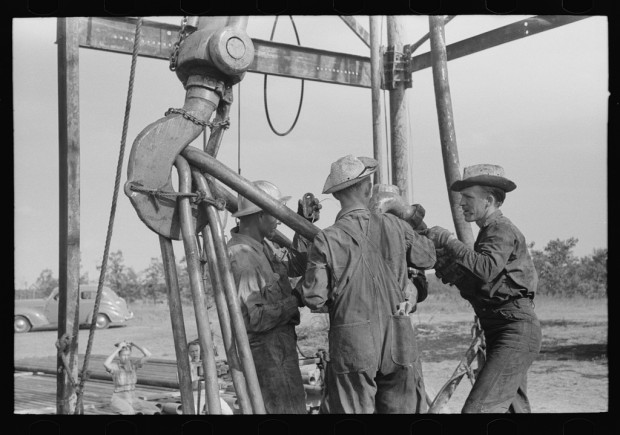

Russell Lee / Library of Congress

Workers in an oil field near Seminole, Okla., in 1939.

An upsurge of earthquakes linked to the oil and gas industry continues to rattle Oklahoma, but new research suggests most of the significant earthquakes recorded in the state over the last century also were likely triggered by drilling activity.

The findings, published today in the Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, link many historical Oklahoma earthquakes presumed to be natural in origin to oil and gas operations where wastewater and other fluids were pumped underground — a phenomenon known as induced seismicity.

“There’s a very, very, very small chance that it was just a fluke that these earthquakes happened to pop off where these wells were going in,” says U.S. Geological Survey seismologist Susan Hough, who co-authored the peer-reviewed paper.

The research is based on data of 3.5-magnitude or greater earthquakes and a comprehensive catalog of well sites that Hough and co-author Morgan Page of the USGS built with information extracted from archives of often-handwritten county oil and gas records.

Click here to read "A Century of Induced Earthquakes in Oklahoma?" by U.S. Geological Survey seismologists Susan Hough and Morgan Page. The paper was published by the Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America.

The research suggests links between earthquakes and oil and gas operations dating back to the 1920s, including wastewater injection into disposal wells — the activity scientists think is fueling the state’s recent earthquake uptick — and another process known as “enhanced oil recovery,” where fluid is pumped underground to boost oil production.

The data suggest two high-profile Oklahoma earthquakes in the 1950s likely were induced: the 5.7-magnitude El Reno temblor that toppled chimneys and smokestacks and left a 50-foot crack in the state Capitol in 1952, and a 3.9-magnitude quake that shook Tulsa County in 1956.

All but one of the earthquakes recorded that decade were located “close to an injection well that was permitted prior to the earthquakes,” Hough says. The new research suggests Oklahoma’s naturally occurring earthquakes are concentrated in the southeastern part of the state near the Ouachita structural belt, where an estimated 4.8-magnitude temblor occurred in 1882.

Despite scores of scientific evidence from university and government researchers, oil and gas companies and officials in Oklahoma have been reluctant to link earthquakes to the industry, which drives the state’s economy and supports one in five jobs.

In public meetings, state Capitol hearings and interviews with StateImpact, oil industry representatives, state seismologists, lawmakers and public officials all pointed to earthquakes like the 1952 El Reno event as evidence of the state’s history of significant, but naturally occurring earthquakes.

“That’s actually what motivated the study in the first place,” Hough says. “There’s been the assertion that you have clusters of activity normally.

In April 2015, the Oklahoma Geological Survey formally acknowledged the connection; Gov. Mary Fallin followed suit, publicly, in August.

The Oklahoma Corporation Commission’s initial reaction was passive compared to other states experiencing industry-linked earthquakes. But the response from Oklahoma’s oil and gas regulator has evolved to include rule changes, permit scrutiny and broad directives demanding oil and gas companies shut down disposal wells or slash the amount of waste fluid they’re pumping underground.

The new research suggests that Oklahomans have lived with man-made, oil and gas earthquakes since statehood. “They’re not some new boogeyman that’s emerged since 2009,” Hough says.

While the study suggests oil and gas-linked shaking is nothing new, Hough says the intensity of the recent earthquake boom, which started in 2009, far surpasses any seismic activity recorded before in Oklahoma.

“Things have ramped up,” she says. “These earthquakes might not be new, but the rate and hazard has certainly increased.”