Boats meet in the middle of Tom Steed lake in southwestern Oklahoma in May 2014. Under normal lake conditions, the rocks in the foreground would be submerged.

Joe Wertz / StateImpact Oklahoma

Boats meet in the middle of Tom Steed lake in southwestern Oklahoma in May 2014. Under normal lake conditions, the rocks in the foreground would be submerged.

Joe Wertz / StateImpact Oklahoma

Joe Wertz / StateImpact Oklahoma

Boats meet in the middle of Tom Steed lake in southwestern Oklahoma in May 2014. Under normal lake conditions, the rocks in the foreground would be submerged.

A soggy April and a slow-moving storm system that dumped record rainfall has drenched Oklahoma’s drought. The rain is welcome, but officials and experts warn the relief could be fleeting.

Western and southwestern Oklahoma suffered the most over the last five years. The 2014 wheat harvest was a bust, and evaporating reservoirs forced cities like Lawton, Altus and Duncan to ration water and hold urgent discussions about finding new public water sources.

“We hit our all-time low there around the middle of April,” says Will Archer, manager of the Mountain Park Master Conservancy District, which includes Tom Steed Lake, a reservoir that supplies water to Frederick, Snyder, Altus and a wildlife management area called Hackberry Flat.

Granite rocks marked by a bright white line surround Tom Steed and remind lake-goers of how full the reservoir used to be. “You’d think, ‘Man, we’ll never get there again,’” Archer says.

Today, the water level at Tom Steed Lake is about twice as high as it was a month ago. Archer says the rainfall had an immediate effect on the lake.

“It’s just incredible the difference. The lake looks like it has new life,” he says. With green trees and green grass out in the water, when you drive by, you can really tell what a rise we really had out in the lake.”

The period from April to mid-March was the wettest ever recorded in Oklahoma, says State Climatologist Gary McManus. The rainfall has led to “dramatic reductions” in overall drought conditions, especially in Oklahoma’s westernmost regions, he says.

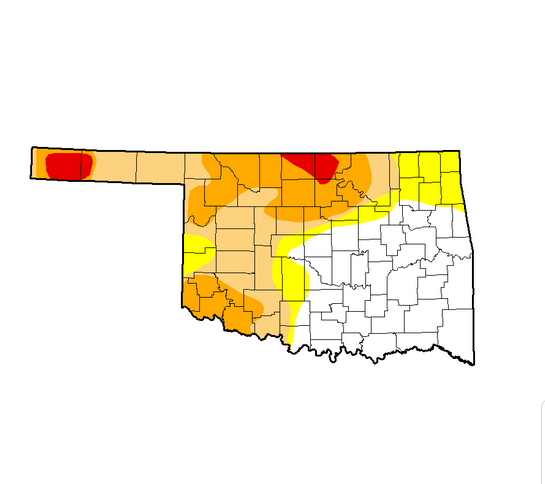

U.S. Drought Monitor

The U.S. Drought Monitor for May 12 shows improvements for Oklahoma, which has no regions under "exceptional," the most intense, drought conditions.

Updated drought maps for the United States were released this morning. The maps divide regions into six groups ranging from zero drought to “exceptional” drought. McManus says some parts of Oklahoma improved by two categories, which is rare. Currently, no region of Oklahoma is experiencing exceptional drought conditions, the most severe category.

The barrage of thunderstorms that spawned tornadoes and widespread flooding throughout Oklahoma on May 6 through May 9 was likely fueled by El Niño — an unusually warm ocean-atmosphere weather system near the equator in the Pacific Ocean. This is one of the strongest El Niños during this time of the year that has been recorded since 1950, McManus says. There are also some signs that global climate patterns tied to the Pacific Decadal Oscillation and the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation — might mean Oklahoma is poised for longer-term drought relief.

“Those are high-falutin’ terms, but it looks like we might be coming out of the worst of the oceanic configurations,” McManus says.

Logan Layden / StateImpact Oklahoma

Will Archer, manager of the Mountain Park Master Conservancy District, at the Tom Steed Reservoir dam.

Forecasting short-term weather events is hard, and predicting long-term climate patterns is exceptionally challenging. The variables are endless. One complication is that there are often short periods of wet weather that pop up in the middle of longer-term droughts. Oklahoma saw such a rainy blip from October 2011 to March 2012, McManus says. The drought then returned.

“We’re just a very hot and dry summer away from having drought conditions return where they’re now leaving,” he says. “I always urge everyone to plan for dry periods because we know they’ll return. They always return.”

Will Archer, the manager at Tom Steed Lake, says residents and local and state officials have to make sure the recent rainfall doesn’t wash away conservation efforts and long-term water planning.

The city of Altus, for example, is restoring wells that tap aquifer water across the border in Texas. Lawton is dredging Waurika Lake so the city can access more of the water stored there, and Duncan is considering new pipeline projects to increase municipal water supplies.

“In southwest Oklahoma, we’re looking at 5 and 10-year plans,” he says. “We’re not only preparing for this drought, but we’re in the mindset to prepare for the next drought.”

Archer says that while Tom Steed Lake now has twice as much water as it had a month ago, it’s less than 50 percent full. It seems that when it comes to water planning in drought-prone areas, it’s best to look at the reservoir as half-empty.