The Lesser Prairie Chicken

Larry1732 / Flickr

The Lesser Prairie Chicken

Larry1732 / Flickr

Joe Wertz / StateImpact Oklahoma

A group of bird watchers at the Selman Ranch, which hosts the Lesser Prairie Chicken Festival in northwest Oklahoma.

Betsy Searight and her husband John drove from all the way from New Jersey for this opportunity: Wake up at 4 a.m., huddle against the cold, and sit silently and motionless for hours hoping to watch a Lesser Prairie Chicken peep show.

Oklahoma Department of Wildlife Conservation

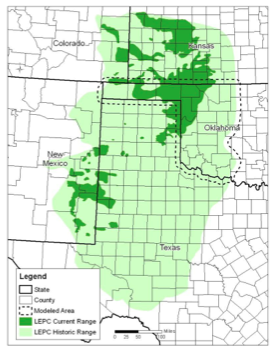

The current and historical range of the Lesser Prairie Chicken.

After a long fight between Oklahoma and the U.S. government, the Lesser Prairie Chicken goes on the federal threatened species list later this month.

To find out how the listing will affect Oklahoma and why the bird is worth protecting, we took a trip to the High Plains of northwestern Oklahoma.

“This is the prize,” Searight says. “Just seeing this thing of nature that’s so hidden from views.”

The sun won’t rise for more than an hour. A bus has just dropped a dozen of us off in the middle of a short-grass prairie near Buffalo in northwest Oklahoma.

“The males are fighting for the dominant spot, and every once and a while a female will creep up and there will be a quick mating,” Searight says. The males will go on expressing their dominance by who gets what spot.”

Lesser Prairie Chickens don’t really like to be watched while they’re mating, which is called “lekking.” To catch the show, you have to hide. This is the main event at Oklahoma’s Lesser Prairie Chicken Festival, an annual event organized by the Oklahoma Audubon Council.

We heard plenty of Lesser Prairie Chickens, but we didn’t see any lekking, which disappointed all the bird-watchers. The game birds might have been spooked by a noise we made or our silhouettes in the tents. They’re elusive, but Allan Janus with the Oklahoma Department of Wildlife says it’s harder than ever to find one of these birds.

“The species has dropped,” says. “We were down to about 34,000 birds two years ago. Then it dropped down to about 17,000 birds.”

Larry1732 / Flickr

The Lesser Prairie Chicken

That’s a big drop from the two million that used to roam in Oklahoma and four neighboring states. In Oklahoma alone, officials estimate there are only 3,000 Lesser Prairie Chickens left. The birds used to inhabit 22 counties, but are now spotted in only nine. Habitat destruction is one reason for the decline, says Janus.

Looking at the horizon from the window of the camouflage tent the Searights agreed to share with me, I can see a line of blinking red lights in the distance — It’s a wind farm. There are a lot of wind farms out here, and more are planned.

There’s also an oil boom in western Oklahoma. Rigs, pump jacks and pipeline compressor stations have moved in. Janus says it’s all helped to drive the birds out.

“These birds are native to an area that didn’t have trees,” he says. “So anytime you have these potential perches for birds of prey they avoid those areas.”

Janus described the Lesser Prairie Chicken as an “indicator species,” the health of which portends other birds, like quail. Charlie Rouse, a birder from Geneva, N.Y., who traveled to Oklahoma with his wife Lisa for the festival, agreed.

“It’s all in the web of life,” he says. “Everything that affects one species eventually affects another.”

State wildlife officials have been working to protect the bird, which, in 1995, was first petitioned to be listed as a federally threatened species.

In recent years, Oklahoma and other states have worked feverishly to prevent a federal listing. Janus with the state Wildlife Department says the federal government puts too much blame on industry, and not enough on the drought, which has decimated bird populations and led to steep annual declines.

Oklahoma joined Colorado, Kansas, New Mexico and Texas in a conservation plan by which oil, wind and other companies, as well as farmers, could pay a fee to offset the habitat destruction. Janus and other ODWC researchers also built a sophisticated interactive map to help steer developers away from prime Prairie Chicken habitats. Attorney General Scott Pruitt says the cross-state collaboration was unprecedented.

“We expended roughly $26 million dollars to try to avert the listing of the Lesser Prairie Chicken.”

But it didn’t work. In March, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service finalized its plans to list the bird as a threatened species, which goes into effect on May 12. Pruitt is now suing the federal agency, which he says settled with environmental groups and circumvented state involvement in federal rule making.

Environmental groups praised the listing, but vowed to do more. WildEarth Guardians, the Center for Biological Diversity and Defenders of Wildlife are mounting a legal challenge to the listing and pushing for a full “endangered” designation.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service endorsed the five-state Lesser Prairie Chicken conservation plan, so Janus said the federal listing will likely have little effect on day-to-day conservation efforts in Oklahoma.

But Janus says there’s another worry. Farmers and oilfield workers who have assisted state researchers might not be as cooperative with federal agents.