Norman, Okla., well operator Scott Lewis with Well #52, one of 36 that serve Norman.

Logan Layden / StateImpact Oklahoma

Norman, Okla., well operator Scott Lewis with Well #52, one of 36 that serve Norman.

Logan Layden / StateImpact Oklahoma

Joe Wertz / StateImpact Oklahoma

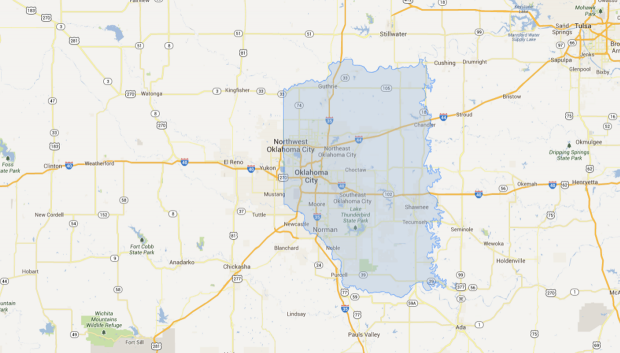

The Garber-Wellington Aquifer is part of the Central Oklahoma aquifer, which every major city in the region uses — except Oklahoma City.

Moving water from the southeast Oklahoma to Oklahoma City is highly controversial. The battle over who controls water across most of that part of the state still has the state, city and tribal governments tied up in court after more than two years.

If only there was another large source of water, near the metro, that OKC could use. Well, State Sen. Jerry Ellis, D-Valliant, says there is: The Garber-Wellington Aquifer. And he’s tired of seeing Oklahoma City take water out of his district in the far southeast corner of the state.

“They’ve got other things. They’ve got groundwater. They’ve got the Garber-Wellington Aquifer there,” Ellis says.

StateImpact had never heard of the Garber-Wellington Aquifer. Neither had any of the half-dozen or so OKC residents we asked outside the Utilities Department downtown.

Logan Layden / StateImpact Oklahoma

Norman, Okla., well operator Scott Lewis with Well No. 52, one of 36 that serve Norman.

It’s part of the larger Central Oklahoma Aquifer, an underground water supply that stretches from Guthrie to Noble, Mustang to Shawnee. And every major community in the area relies on it, at least in part — except Oklahoma City. Utilities Director Marsha Slaughter says that’s not how it used to be.

“We started out on wells. The utility started in April 1889 with one well at the stationmaster’s house — the Santa Fe Railroad stationmaster’s house. People brought their own bucket,” Slaughter says.

Relying mostly on shallow wells along the North Canadian River worked — for about 20 years.

“Until about 1910 when we went dry. And there were about 24,000 people here at the time. And there was no water to be had,” Slaughter says. “So we built Lake Overholser, and then we built Lake Hefner to capture rainfall.”

Oklahoma City stopped maintaining its last wells in the early 1990s. And there are no plans to turn back to the aquifer now, despite the intense resistance to taking more water from other parts of the state.

“So 250,000 gallons a day from a water well means you need four wells to make a million gallons,” Slaughter says. “And if you’re looking to make a peak demand of 200 million gallons a day, wells are just impractical for us, for the size of system that we operate.”

Even adding Garber-Wellington water to the mix poses problems. Just ask Ken Komiske, utilities director in Norman, where aquifer water provides about one-third of his city’s needs.

“There’s issues with the aquifer, too,” Komiske says. “It’s not from pollution. It’s not from contamination or industrial uses, but it’s a heavy metal aquifer. So, just in the rocks are a lot of minerals like arsenic, chromium, cadmium, vanadium.”

There are federal regulations that have to be adhered to and standards to meet when dealing with those potentially dangerous elements.

And any aquifer water Oklahoma City uses leaves less for surrounding communities, many of which already turn to Oklahoma City for water when their wells go dry during droughts. But Slaughter says that doesn’t stop thousands of residents — within the city limits — from living off the water grid.

“We have about 14,000 houses inside the city — particularly on large lots — who have their own water supply systems,” Slaughter says. “Lots of lovely homes on very large lots are very independent.”

But that independence might not last. The state water regulator is studying the Garber-Wellington. The Oklahoma Water Resources Board will eventually consider putting a limit on its use to keep it from being depleted, much like the recent maximum annual yield determination for the Arbuckle-Simpson Aquifer. That process that went on for 10 years.