‘Something that can’t be replaced’: What a turnpike project could mean for Oklahoma wildlife

-

Beth Wallis

With a thumb wedged between a beak, WildCare Oklahoma veterinarian Dr. Kyle Abbott delicately threaded a feeding tube down the throat of an adult male bald eagle. The massive bird’s tail feathers are stained a deep rust color from the red Oklahoma dirt and bound in bubble wrap to keep it from damage while moving around in its crate.

If all goes well, the raptor will soon have a second surgery to repair the broken humerus bone that brought it to WildCare. Then it faces months of physical therapy before returning to the wild.

Beth Wallis/StateImpact Oklahoma

Animal care staff member Bryce Messer restrains an adult male bald eagle as WildCare veterinarian Dr. Kyle Abbott administers a feeding tube. A broken humerus is usually indicative of being struck by a car or flying into a telephone pole or telephone wire, Abbott said.

WildCare is a nonprofit wildlife rehabilitation facility based out of Noble, Oklahoma. It takes in over 7,000 wild animals annually, making it one of the largest facilities of its kind in the country. It also sits about half of a mile from the proposed route of a 19-mile, $650 million turnpike extension.

The ACCESS Oklahoma Turnpike project from the Oklahoma Turnpike Authority is a 15-year, $5 billion project to build several turnpike routes in central, southern and northeastern Oklahoma. There’s been a substantial public backlash against the project — an opposition group with over 8,000 members on its Facebook page, two lawsuits and multiple packed community meetings full of posterboard-wielding residents.

Among mounting concerns about the displacement of families, fair compensation for property acquisition and an intrusion on a rural lifestyle, residents who regularly see deer grazing in their yards and eagles soaring overhead are also wondering, what’s going to happen to all the wildlife and the facility that takes care of them? And how far does the law go to protect them?

Inger Giuffrida, executive director of WildCare, said the turnpike could have serious repercussions.

“Were this route to go through, we don’t know at this point whether or not the pollution, the noise, the light would make the work we do untenable. My gut instinct is yes,” Giuffrida said. “And it just again seems wrong that a few people whose role is to build turnpikes can undo the work of thousands. Let alone the displacement of thousands.”

Beth Wallis/StateImpact Oklahoma

WildCare Executive Director Inger Giuffrida stands outside of the front door of the rehabilitation facility. WildCare began as a home-based wildlife rehab in 1984 and has since grown to one of the largest centers in the country.

‘Once you put that road in, it cannot be undone.’

While walking around the outdoor enclosures at WildCare, Education and Outreach Coordinator Kristy Wicker stopped near one fenced area containing a coyote. The animal was in distress, running and pacing back and forth, mouth open and panting, with the whites of its eyes flashing.

Wicker told StateImpact that just the presence of humans in the vicinity of a wild animal can cause stress.

“You and I aren’t talking very loudly,” Wicker said. “But still, he knows we’re here, and that’s making him very nervous. And we certainly don’t want that if an animal is injured or compromised already.”

In addition to the immediate physical danger fast-moving cars present to wildlife, research suggests the noise alone from the roads trigger declines in wildlife abundance, further fragmenting the animals’ habitats. There’s a significant body of research showing the detrimental effects anthropogenic noise has on wildlife.

Beth Wallis/StateImpact Oklahoma

WildCare’s 5000th patient of the year, an injured roadrunner receives an injection of fluids by veterinarian Dr. Kyle Abbott.

Giuffrida said stress can lead to grave complications for hurt or sick animals, and that they often injure themselves trying to get away from humans.

“So that’s why you have an animal that will jump higher than it can to try to escape noises or anything that feels like a threat. You’ve heard of animals chewing their paws off in traps,” Giuffrida said. “And that’s one of the reasons that I’m so profoundly concerned about the noise that this turnpike is going to bring, because it will create a constant level of stress for the animals here.”

Giuffrida said she’s also worried about an increase in roadkill and orphaned baby animals. She said past road projects have yielded influxes of injured animals hit by cars and abandoned young, and she expected the same will happen with the new turnpike extensions.

Ultimately, Giuffrida said, WildCare may have to move. She doesn’t know where, when or how, but that it will probably cost the organization in the ballpark of $2.5-5 million. The facility is currently in need of several new enclosures and equipment, but decisions on improvements are stuck in limbo.

“That’s something we’re trying to determine right now as an organization.” Giuffrida said. “Part of me is just furious that I have to spend our time, that our staff has to go through that stress, that our board has to go through these considerations, rather than focusing on the important work that we do, day in and day out.”

Beth Wallis/StateImpact Oklahoma

A WildCare staff member feeds a baby squirrel. For the last three years, the center has taken in over 7,200 animals yearly.

Kirsten McCullough, the environmental manager for the ACCESS program, acknowledged WildCare’s concerns about having to relocate.

“[WildCare is] not sure right now if their facility is going to be able to stay based on the location of the [turnpike] alignment and whether the noise and other things are going to be too much of an impact,” McCullough said. “And that’s really a decision that they’re going to need to make.”

Beth Wallis/StateImpact Oklahoma

A WildCare staff member holds a baby Eastern Red Bat. The bat was brought to the rehab center with several of its siblings.

McCullough said the OTA is committed to work with WildCare on impact mitigation strategies, and the agency is considering tactics such as wildlife crossings to facilitate access to resources like Lake Thunderbird and creating additional habitat near the lake.

But Giuffrida said cutting off wildlife from cover, food and water will have devastating effects on the local ecosystem, and she’d rather see no turnpike at all than have to weigh mitigation strategies.

“This is not a feel-good issue. Wildlife is important. It’s intrinsically important,” Giuffrida said. “We rely on wildlife more than we recognize for so many different things. (…) That we as a state do not value the wildlife and the wild habitat that they rely on is, I think, one of the greatest tragedies of our leadership right now. Once you put that road in, it cannot be undone.”

How far does wildlife protection law go?

Some animals in the path of the turnpike are protected by federal law, such as eagles and whooping cranes. But those protections only go so far when confronted with the interests of industry.

The bald eagles that frequent Lake Thunderbird are protected by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act and the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act. But built into these protection laws are mechanisms that allow industry to still develop in wildlife habitats, mainly in the form of incidental take permits. “Take” refers to actions or attempts to “harass, harm, pursue, hunt, shoot, wound, kill, trap, capture, or collect” an animal.

Tulsa-based U.S. Fish and Wildlife biologist Kevin Stubbs said legal routes exist to continue developing around protected animals like eagles, but that every effort should be made to avoid impact.

“You can apply for a permit if there is no way to avoid impacting the nest, but we recommend looking at options through modifications of the route or timing of construction to avoid impacts to the nest tree or nesting eagles,” Stubbs wrote in an email to StateImpact. “We work with ODOT and OTA on all their projects to minimize impacts and get permits if needed.”

McCullough said the OTA would only acquire a take permit to move nests as a last resort, and that the agency would “make all effort” to avoid needing to remove nests or nesting trees.

Lena Larsson is the executive director at the Sutton Avian Research Center in Bartlesville. The nonprofit maps eagle nests across the state and is often consulted by ODOT on whether these nests will interfere with road construction. The center depends on data collected by citizen scientists.

“I don’t have perfect data,” Larsson said. “So we really depend on the public to inform us of their observations. So they can go on our website and say, ‘Hey, there’s an eagle nest here,’ and [the Sutton Center] can go and check it out and verify that it is indeed an eagle nest and if it’s active or not. And then we can have our volunteers start monitoring that nest.”

Larsson said though residents around the southeast Norman area frequently see bald eagles, the raptors are likely just using the Thunderbird area to hunt, rather than nest. Currently, Larsson only has one nest mapped near the lake.

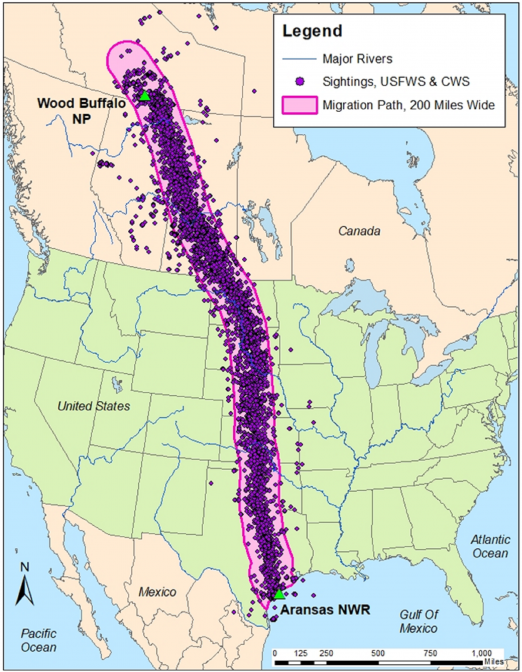

Whooping cranes are another protected animal residents have spotted in the southeast Norman area. These cranes are protected by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act and the Endangered Species Act.

Stubbs said the cranes’ only protected critical habitat in Oklahoma is at the Salt Plains. While whooping cranes have been observed stopping around Lake Thunderbird during migration, McCullough said that doesn’t prevent development from happening in the area when the birds aren’t around.

Courtesy of US Fish and Wildlife

A map showing the migratory route of the endangered whooping crane.

“If whooping cranes are spotted within even a mile of the construction site, we stop and make sure that they’re not harassed or bothered until they depart the area,” McCullough said. “And that’s a pretty standard note, because the whooping cranes are a protected species that we put in all of our construction projects.”

Julia Reynolds chairs the Red Earth Group, which is the Norman chapter of the Sierra Club. She said the organization is especially concerned about whether the whooping crane will still be able to hunt around Lake Thunderbird during migration season.

“If the wetlands are too disturbed by roads and humans, then [whooping cranes] can’t really go there,” Reynolds said. “And it makes fewer places available for them to feed along their migratory route all the way down to the Gulf of Mexico, around Texas and Louisiana. (…) This turnpike could be a really major setback as they rebound from the brink of extinction.”

The OTA will also be conducting environmental impact surveys, which McCullough said will be completed prior to any property acquisition — except in instances where residents have already approached the OTA about buyouts.

McCullough said there will be several studies in each construction area, including: a threatened and endangered species habitat assessment and surveys focused on cultural resources, archeology and historic property. Each survey takes a few months, and she said the agency plans to have all of them completed within a year.

‘Something that can’t be replaced.’

Brigitte Kersten-Gates has lived in a house tucked away in the quiet woods around southeast Norman for 24 years. She frequently calls the land her and her husband’s “paradise.”

“It’s a lot more peaceful,” Kersten-Gates said. “You’re not in the city. You don’t hear sirens constantly going off. You don’t hear your neighbors screaming and yelling at each other. You’re out here, you’ve got nature. Nature calms you.”

Courtesy of Brigitte Kersten-Gates

Brigitte Kersten-Gates says she has thousands of pictures collected over the years from her mounted wildlife cam.

Kersten-Gates previously suffered a heart attack that left her heart working at about 35% capacity. Hearing nothing but the wildlife and the wind through the trees doesn’t just help her health, but she said it’s also “good for the soul.”

But soon, the tapping of woodpeckers and hoots of owls could be drowned out by the proposed turnpike extension, which is set to run through the middle of her property. She often quotes a song from Counting Crows:

“Don’t pave paradise and put up a parking lot.”

Kersten-Gates is full of stories about interactions with local wildlife. From the occasional roar of a mountain lion to mischievous racoons, from hungry bobcats to watching a deer give birth to twins in her driveway, she cherishes the flora and fauna that surround her home.

She’s even made her property a Certified Wildlife Habitat through the National Wildlife Federation. Though the designation doesn’t come with legal protections, it recognizes the area as having adequate food, water, cover, places to raise young and sustainable practices to support the local wildlife.

Beth Wallis/StateImpact Oklahoma

Brigitte Kersten-Gates stands next to a sign designating her land as a Certified Wildlife Habitat from the National Wildlife Federation.

To Kersten-Gates, this ecosystem deserves to be protected.

“I want to be able to build a garden if I want, to watch the wildlife, watch the birth of a baby deer,” Kersten-Gates said. “I mean, and the baby squirrels and stuff like that, even though they tear up your plants. I’m ok with that! I get to see all that. And to me, that means a lot. I mean, this is life. Something that can’t be replaced.”