OSU researchers test water quality at Grand Lake. From left to right: Abhiram Pamula, Muwanika Jdiobe and Levi Ross.

Courtesy of Oklahoma State University

OSU researchers test water quality at Grand Lake. From left to right: Abhiram Pamula, Muwanika Jdiobe and Levi Ross.

Courtesy of Oklahoma State University

Two years ago, Muwanika Jdiobe — then a master’s student at OSU’s School of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering — was approached by his advisor to solve a problem:

How can we monitor water for harmful algal blooms efficiently and autonomously?

Oklahoma’s Grand Lake is no stranger to harmful algal blooms , which happen when colonies of algae grow out of control and can cause illness or death in animals and people. Using Grand Lake as a testing area, the researchers wanted to find a way to predict when these blooms could become an issue for the surrounding communities.

While buoys and manned boats are sometimes used to monitor algae blooms, the researchers wanted a device that could drive itself to specific GPS coordinates. They also wanted something small enough to fit into narrow streams and that didn’t need the excess fuel it takes to carry people around.

“We sat down and thought that this is a very good problem to tackle, and it would have an immediate impact to the society and the community in which we’re living,” Jdiobe said.

Within a few months, Jdiobe and a team of researchers came up with MANUEL, which stands for Mobile Autonomously Navigable USV (Unmanned Surface Vehicle) for Evaluation of Lakes. MANUEL is a self-driving boat capable of collecting water qualities, such as temperature, turbidity and certain chemical content.

Researchers David Lampert, Mark Krzmarzick and Jamey Jacob also worked and advised on the project.

While MANUEL isn’t the first device of its kind, Jdiobe said it’s substantially smaller and cheaper than other models. He hopes the accessibility of MANUEL will appeal to resource-strapped areas dealing with water quality issues, like the communities around Grand Lake — or even communities on the other side of the world.

Jdiobe, who is from Uganda, sees global potential in the project. He hopes someday he can bring MANUEL back to his home country to address water quality issues there. He said he remembers himself, friends and family suffering from typhoid, which generally comes from drinking contaminated water.

“Where I grew up, fresh water was not a guarantee for everybody,” Jdiobe said. “So I look at this platform as a very, very viable platform to help in countries like Uganda where I’m coming from.”

Courtesy of Oklahoma State University

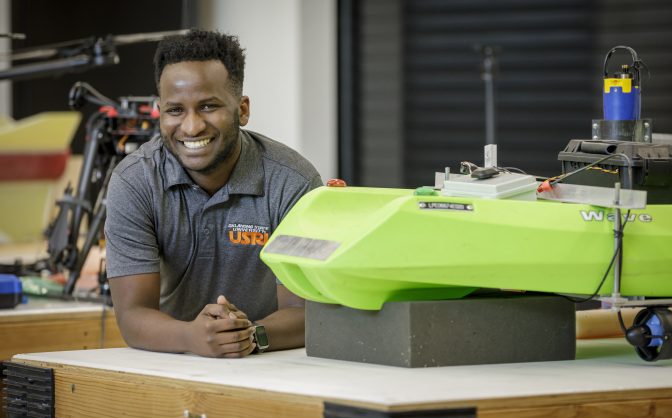

Muwanika Jdiobe works on MANUEL, an autonomous, water-sensing boat.

MANUEL works through a combination of autonomous decisions and “hints,” as Jdiobe calls them. A researcher plugs in coordinates of where it wants MANUEL to test water, and the boat uses the same autopilot system used in drones to drive itself out to these areas. He said researchers can communicate with the device via a ground station or transmitter.

“Sometimes, we have a transmitter and a receiver which you can control, like anyone playing a video game,” Jdiobe said. “When you go to the field, you don’t feel like you’re working. It feels like you’re playing video games, but you’re actually producing meaningful data that is actually going to change some lives.”

When MANUEL detects conditions in the water that can lead to harmful algal blooms, the researchers said there’s a few things that can be done: local authorities can get the word out not to swim in or drink the affected water, and chemicals or other novel methods can be used to treat the water.

Abhiram Pamula, an environmental engineer who was a civil engineering Ph.D. student during MANUEL’s development, said in addition to monitoring the water, the data can help scientists better understand the impact agriculture and other human activities have on water quality.

Pamula said fertilizer runoff is a major driver of harmful algal blooms. Nitrogen and phosphorus from fertilizer wash out into streams and reservoirs — an issue made worse with seasonal heavy rains. Summer temperatures can then activate the blooms.

But Pamula said there are still lots of unanswered questions about how these blooms form: What kinds of microbes are causing these blooms? What exactly is making them grow? What kind of cyanobacteria is affecting bloom conditions?

“It’s different from reservoir to reservoir, because upstream conditions and the land management activities are so different and vast,” Pamula said. “It’s not easy to quantify what exactly is the reason that’s happening, that’s causing these blooms.”

Pamula said algae blooms are site-specific phenomena that change from place to place based on climate and manmade interactions. Like Jdiobe, he hopes the research can be scaled up globally to get a fuller picture of how algae blooms happen all over the world.

As for where the device can go from here, Jdiobe said the technology can be expanded to detect more than just algae, but also other contaminants like heavy metals. Pamula said he wants to see a version of MANUEL that can be submerged to detect water quality beneath the surface. OSU researchers are now working on an upgraded version of MANUEL as the team continues to learn more.

Pamula said the research is just the beginning of a deeper dive into how microbes react to different environments. The possibilities, he said, could even be inter-planetary.

“I’ve just scratched the surface in understanding this,” Pamula said. “Microbes exist everywhere. It doesn’t even have to be this planet — it can be any other planet. … If you can understand how these microbial activities [are] going on in this world, this will just be a start, the beginning for me to understand a lot more in the future.”

For now, the researchers hope MANUEL can help small towns with small economies — especially those that benefit from water-based recreation in the summer. With more frequent monitoring, researchers can keep an eye on the potential blooms.

Courtesy of Oklahoma State University

Muwanika Jdiobe beside the autonomous, water-sensing boat, MANUEL.

The scientists said the project has the potential to further the world’s understanding of water conditions and eventually create opportunities for communities around the globe to keep their residents safe from contaminated water.

“I’m just hoping that the future is bigger, brighter,” Jdiobe said. “And we can have [an] impact not only on the people of Oklahoma or the United States, but have the whole world benefit from the technologies that are being developed at Oklahoma State University.”