Calumet Elementary School

Robby Korth / StateImpact Oklahoma

Calumet Elementary School

Robby Korth / StateImpact Oklahoma

Robby Korth / StateImpact Oklahoma

Calumet Elementary School students read together in spring 2020. Older students and younger students would team up to improve their reading, however programs like this have been scrapped because of COVID-19.

Lindy Renbarger had to reinvent everything.

The principal of Calumet Elementary is accustomed to doing it all. In her decade at the helm of the school with less than 200 students she’s taken it from a school that scored a “C” on the state report card to regularly getting an “A.”

In spring 2020, StateImpact visited Calumet Elementary for a story about that transformation in the lead up to spring assessment tests.

Renbarger led a whirlwind tour of a school where reading was an obvious priority. In the hallway at the heart of the school a group of first and sixth graders read books together.

Reading comprehension is an incredibly important part of child development and the end of year assessments.

That story was killed when the state – and ultimately the nation – opted to cancel spring assessment tests because of the coronavirus. But the tests are back on in spring 2021, though with changes.

“I do feel good about it, but I don’t know that we would pull off an A,” Renbarger said.

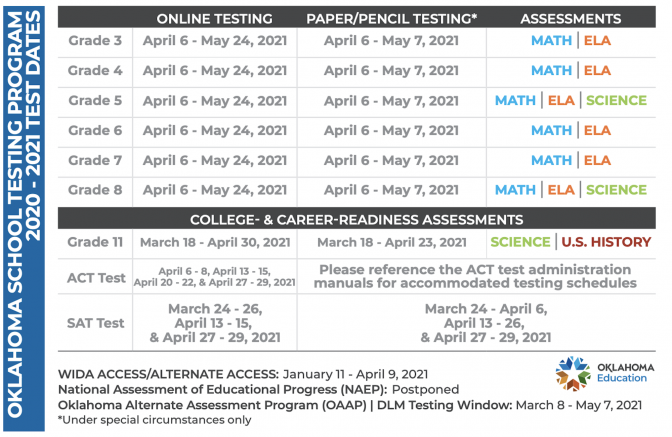

Oklahoma State Department of Education

Oklahoma’s revised spring assessment test window.

In a normal school year, districts are graded off of their students’ performance on end of year assessments in late spring. Federal law mandates states test students for English, math and science in third through eighth grades and one time in high school.

But those grades are something that schools fret over because they have real consequences. And with Oklahoma’s legislature taking action this session to make it easier for students to transfer, the grades schools receive are important. Losing enrollment equals a loss in state funding.

Grades won’t be given this year after the state board of education voted unanimously to suspend them because of the COVID-19 pandemic in December.

The test results will be used instead to set a baseline for assessments moving forward.

“This will be different from any other year so how the data will be used will be very different,” said Joy Hofmeister, Oklahoma’s State Superintendent for Public Instruction.

Districts and state leaders need to have a good understanding of where there are gaps in instruction across Oklahoma, she said.

Hofmeister said teachers and administrators in most districts probably have a good idea of how students are performing.

“But that is different than a state level view,” she said. “And it’s important that we are able to see that as a state and that we can look at these particular student groups that really are going to require additional levels of support.”

Some educators wanted to do away with the tests altogether this year. Last summer, former teacher and Tulsa Democratic State Representative John Waldron penned a letter calling for just that. The reasoning, Waldron wrote, is the tests will give leaders an inaccurate baseline of where students actually are.

“It’ll be like a baseball statistic with an asterisk,” he said.

Waldron is generally a critic of the assessment tests and school report cards. A 20-year teacher, he said they have too much of an effect on how schools operate, and the setting of that baseline can’t be from the pandemic year.

“When you measure a phenomenon, you change the phenomenon,” Waldron said. “And there is this wag the dog effect where the test becomes the driver of good instruction because it provides a clear, measurable outcome.”

State education leaders actually agree with that sentiment. But Hofmeister said there needs to be a way to measure success in schools.

Tests can’t be the end all, be all of how students and teachers operate over the course of the year, Hofmeister said.

Instead educators need to take a look at the full picture of a student to tell if they’re successful.

“Here’s another tool,” she said. “And then we use that for that final snapshot to then say, OK, now we can also continue to unlock resources for additional intervention.”

Oklahoma’s testing window is wide open and will include options for districts to test in evenings and on weekends.

For some assessments, districts will have almost two months to complete them. But some of the nuts and bolts remain unclear, and how tests are administered might vary by district.

The flexibility is welcomed and so is the lack of a grade, Renbarger said.

Teachers have been giving monthly reading assessments to track progress this year, she said. And those will go much further in predicting the success of students. For those struggling with reading, she’s taken matters into her own hands.

“I started a reading intervention group myself,” she said. “So every day I see certain kids and help them out.”

Students will take 15 minutes out of their physical education time to work on reading in Calumet if they’re behind.

Ultimately, not being graded by the state is a relief for Calumet teachers.

“It’s just a test,” Renbarger said. “Let’s just look at it that way. Let’s just take it, and move forward, we know where they’re at.”