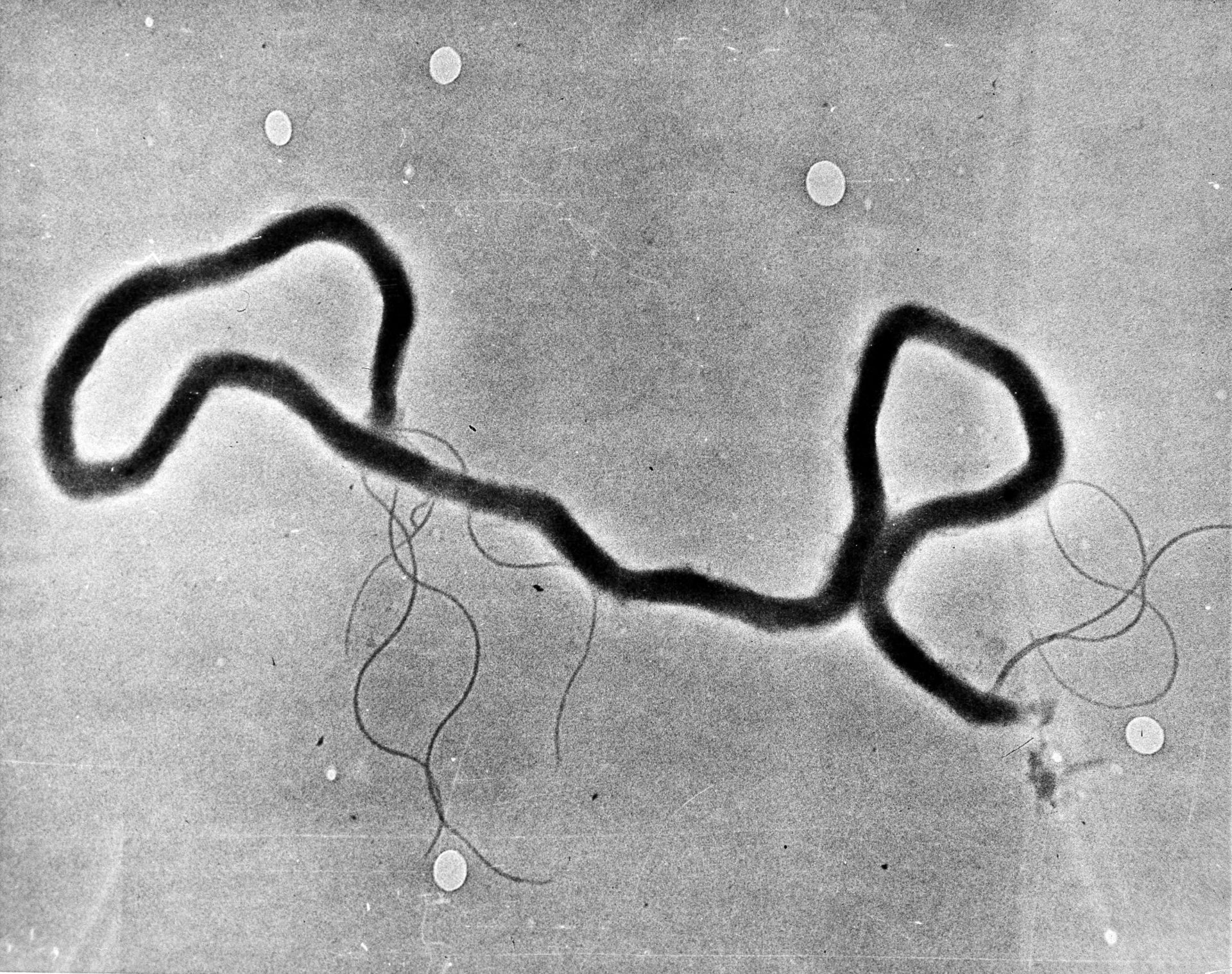

In this May 23, 1944 file photo, the organism treponema pallidum, which causes syphilis, is seen through an electron microscope. (AP Photo)

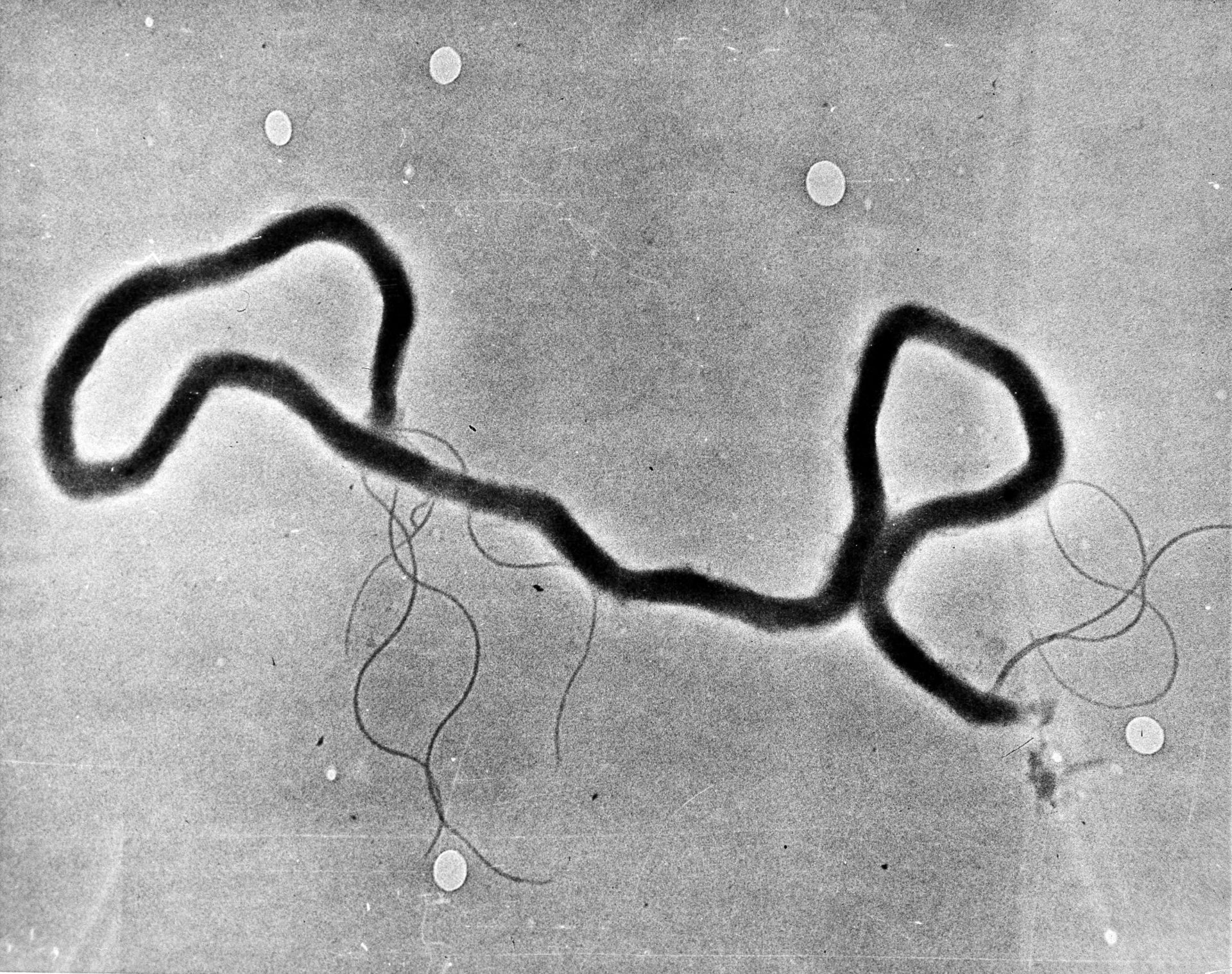

In this May 23, 1944 file photo, the organism treponema pallidum, which causes syphilis, is seen through an electron microscope. (AP Photo)

Over the past six months, we’ve gotten pretty familiar with terms we hadn’t heard regularly before, like contact tracers and infectious disease intervention specialists. But they’re not new. Before the coronavirus, many of Oklahoma’s workers in that sector had their eye on another disease: syphilis.

From 2014 to 2018, Oklahoma experienced a more than eight-fold increase in the number of syphilis cases among women. That’s according to data from the state department of health’s sexual health and harm reduction service. And Since 2014, Oklahoma has seen nearly three times more babies born with syphilis.

In Carter County, near the Texas border in central Oklahoma, public health officials began prioritizing that bacterial infection more than a year ago. Even with mitigation efforts, the county has been experiencing severe outbreaks.

“Our rate, it seems, here in Carter County compared to last year, we’re up 900 percent,” said Mendy Spohn, the state department of health’s regional administrative director for the area.

Carter County is home to Ardmore, one of the state’s worst hit areas in the opioid epidemic. Public officials began ringing alarm bells about a year ago about a burgeoning influx of heroin, which many attributed to a crackdown on opioids. Heroin and opioids are chemically similar, and if someone addicted to opioids can’t find a supply, heroin can stand in.

Rebecca Burton is a public health nurse, who has been serving that area for 26 years. She said that surge in drug use has likely caused the county’s syphilis diagnoses to skyrocket, as dealers accept sex in lieu of cash payments.

She also said syphilis poses a particularly difficult public health challenge.

“It’s not just straight-out disease like (when) you have gonorrhea — throw two pills and the shot at somebody, boom, it’s done,” she said.

First, she said it’s hard to identify, mostly because it can lie dormant or present differently in different people. The infection has gotten nicknames for how sneaky it can be. Then, it behaves differently at different points of infection, so you have to be able to identify which phase it’s in and how to treat that.

But syphilis poses problems not just in individual treatment. The department has to raise awareness about it within the community.

“The general public seems to think that syphilis quit existing many years ago,” Burton said. “When, as you know, it’s actually more of an issue than ever before at this point.”

Spohn said that although health providers aren’t mistaken about the existence of disease, it might not be top of mind for them. So public health officials are working with their partners in care facilities, too.

“We’re having to do a huge provider push to make sure that our emergency rooms, OBGYNs and our other providers are caught up the medical presentation of syphilis and how to diagnose,” she said.

Responding to a syphilis outbreak also takes a resource we’ve been hearing about a lot lately: contact tracers. Infection specialists and the contact tracers track infections in communities. They talk with people who have contracted diseases to investigate who else might have been exposed, then get in touch with those people to explain their risk. Needless to say, those specialists and contract tracers have been busy since the coronavirus struck oklahoma.

“The fact that the spike started right as covid started, I think that contributed to our ability to stay on top of it,” Spohn said. “Because the State of Oklahoma kind of repurposed our disease infection specialists to help us with contact tracing for COVID. That took priority at the time. And I think that you can see that that had some impact. I can’t say that that’s the complete answer as to why that happened. But I do feel like it shows the importance of your disease and intervention specialists and especially with sexual health. And how important they are.”

The coronavirus is just one of the strains that Carter County’s health department and the ones around the state are facing.

It’s October, which means flu season. In a normal year, without a global viral outbreak and a local bacterial outbreak, flu season means busy season.

“Flu vaccine is usually a surge for public health anyway,” Spohn said. “It’s a time when we don’t really take off, during our flu vaccine surge time. We prepare ourselves for that. So adding a flu surge on top of a syphilis outbreak on top of a pandemic, it’s hard to describe.”

It is hard to describe, but she did a pretty good job when she offered this visual.

“Right now, we have a line of cars behind our building waiting for testing. Tonight, we will have a line of cars waiting for their flu vaccine. In the middle of that, we have a family planning clinic. We’re doing phone-based WIC (Women, Infants and Children nutrition assistance) interviews. Becky (Burton) and a couple of other nurses are running two hour syphilis or STD visits for some of these people. Because that’s how long we interview and some of the process can take.”

It’s not just the coronavirus and the syphilis outbreak and the dawn flu season. The last strain is a little bit unexpected and a little bit less obvious.

In early 2018, the Oklahoma State Department of Health was embroiled in a financial scandal, which resulted in hundreds of layoffs across the state. In this sector, it’s common to use the term reduction in force, or RIF, instead of layoff. Needless to say, many in the public health sector were upset.

“My district was down forty two people, and not just because of RIFs,” she said. “Some people were like, ‘We’re done, we’re gone.’ Some retired.”

Despite the shallow bench and competition with other infectious diseases, Carter County has kept some of its focus on the syphilis outbreak.

“When we found out about the syphilis outbreak, it wasn’t like, ‘Oh, we can’t do that,’” Spohn said. “It was, ‘All right, how are we going to make this happen?’ And, you know, we assigned Becky to be that lead for that.”

“It is a juggling act,” Burton said with a laugh. “I won’t lie.”

In addition to letting people know syphilis still exists, Becky said the most important message she wants to share is that seeking help from a local health department is safe.

“I want people to be comfortable and free to come to us, to be tested, to be treated,” she said. “I want them to know we are not here to judge them and we do not report them to the police with their drug use.”