Erika Buzzard Wright embraces a supporter during a press conference about the future of the four-day school week at the Oklahoma State Capitol.

Robby Korth / StateImpact Oklahoma

Erika Buzzard Wright embraces a supporter during a press conference about the future of the four-day school week at the Oklahoma State Capitol.

Robby Korth / StateImpact Oklahoma

Erika Buzzard Wright doesn’t hesitate to admit she doesn’t know what she’s doing.

Before today, she’s never organized a press conference or put together a media kit. That lack of experience hasn’t stopped her from trying to be a voice for rural Oklahomans who like sending their children to school four days a week instead of five.

The Noble school board member and mother of three is making her case to the media, state board of education and lawmakers at the state capitol on a blustery December day.

And the stakes couldn’t be higher.

“If our four-day districts, and there will be some, that if they are forced to go back to five days, they will have to shut their doors,” she told reporters.

The parents and teachers are reacting to new rules created by Oklahoma’s State Department of Education. Those rules say individual schools have to perform at or above state average in English and math proficiency tests. They also say a high school must have a graduation rate at or above the state average, academic achievement targets at or above the state average and post-secondary opportunities on par or better than the rest of the state.

If a school doesn’t meet one of those, then it can’t have an abbreviated week schedule. And because of logistical challenges, if one school fails then an entire district fails with it, school leaders have said in stakeholder meetings with the State Department of Education.

That means of the about 100 districts that use a four-day week, it’s likely only eight would be able to keep the schedule based on the most recently available metrics.

If a school can’t meet state averages, for the welfare of its students, the state needs to step in, said State Superintendent Joy Hofmeister.

“It’s really looking at outcomes only,” she said. “And saying you can have the innovation and flexibility. But to go so very low, below 165 days, keep in mind that’s almost less than half a year, you need to demonstrate as a safeguard for our students that they have their needs met, that they are growing.”

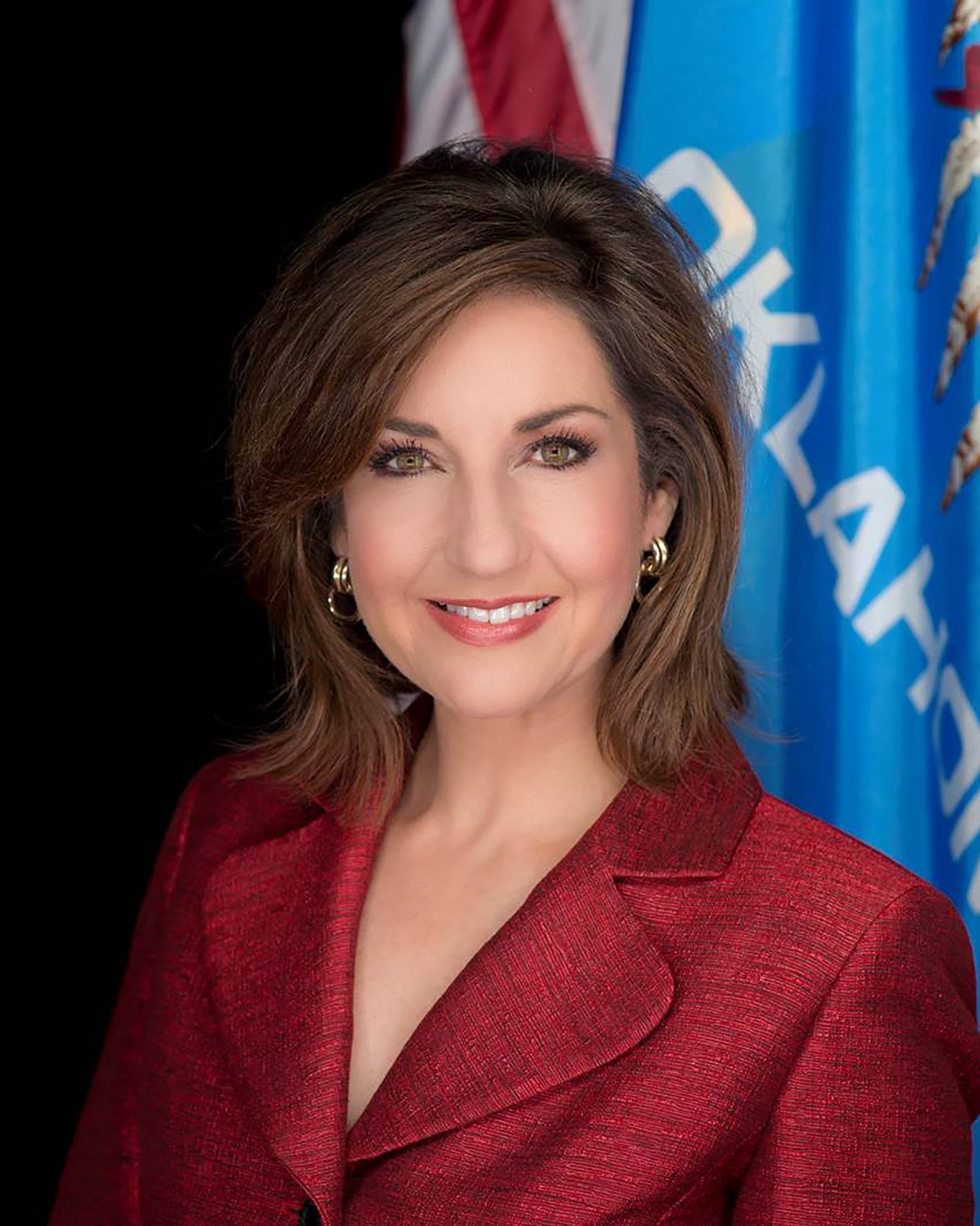

Oklahoma State Department of Education

Joy Hofmeister, State Superintendent of Education

This is just the latest round in a battle between legislators, state officials and local school districts over school calendars.

At the beginning of the decade, Oklahoma lawmakers altered state rules for school year length. Inclement weather had forced students to keep going to school late into the summer because of a requirement that they be in class for 180 days. The rules were changed to 1,080 hours so extra time could be tacked onto fewer days.

School districts began to take advantage. Leaders in rural districts touted an abbreviated week as an opportunity to cut costs in the midst of a budget crisis, though the relatively few studies of the issue show little evidence of significant savings for districts.

The four-day school week advocates argue that the shorter week is helping retain qualified teachers who like the shortened schedule, reducing absences for school and athletics activities on Fridays and the schedule doesn’t seem to have much of an impact on instruction.

Of Oklahoma’s more than 500 school districts, about 20 percent have four-day school weeks.

In the last decade, the abbreviated school weeks have exploded across the western U.S. Most are concentrated in Colorado, Montana, Oregon and Oklahoma. Because they’re a recent phenomenon, any benefits or drawbacks are mostly unstudied. Quinn says because of the lack of general information on four-day school weeks, it’s probably best for children to stay in school five days.

With an increase in funding last year, legislators decided to take a fresh look at four-day school weeks.

“It is time to look at, are we giving our students enough of an opportunity to learn for the long run? And that is not something that happens by just lengthening the school day to get through those 1,080 hours that are required,” Hofmeister said.

Robby Korth / StateImpact Oklahoma

Noble school board member and mother of three Erika Buzzard Wright makes public comments about the four-day school week to the Oklahoma State Department of Education in December.

The change was led by Sen. Marty Quinn, R-Claremore. He said it was important to look at how schools are spending their days because of taxpayer investment.

“We have to show the parents, we have to show the community that the millions of dollars that we’re spending on education, that there is a return on those efforts,” Quinn said. “And we want to spend as efficiently as possible.”

In early 2019, Oklahoma lawmakers debated the fate of four-day school weeks, eventually passing a law to have schools apply for a waiver if they planned to go to school less than 165 days. In early 2020, the issue is likely to come up again. That’s thanks to the group of parents and teachers united to save the abbreviated school week.

They’ll be asking the State Board of Education to alter the rules, which will likely be considered in January. Then, if the rules the board passes aren’t satisfactory, advocates said, they’ll ask the state legislature not to approve the rules before they go into effect in fall 2021. And they’ll have a simple message for lawmakers along the way, Wright of Noble said.

“If you don’t reject these rules in the spring, we are going to reject you at the ballot boxes across Oklahoma in November,” Wright said.