The Cleveland County courthouse in Norman, Okla.

Jackie Fortier / StateImpact Oklahoma

The Cleveland County courthouse in Norman, Okla.

Jackie Fortier / StateImpact Oklahoma

Jackie Fortier / StateImpact

Narcan, also known as Naloxone is an opiate overdose antidote.

The ongoing court case against opioid manufacturer Johnson & Johnson highlighted the role that doctors, and the medical boards who regulate them, have played in the continuing public health crisis.

The state is asking a court to order the opioid manufacturer to pay more than $17 billion to ‘abate the opioid crisis’ in Oklahoma. During the seven-week trial, which wrapped up in July, attorneys for the state claimed that Johnson & Johnson along with other drug giants, waged an aggressive marketing campaign beginning in the 1990s to convince patients and doctors that pain was a vast, undertreated problem – and that the solution was more opioids.

Lawyers for Johnson & Johnson argued instead that the state has failed to regulate physician’s opioid prescribing practices properly.

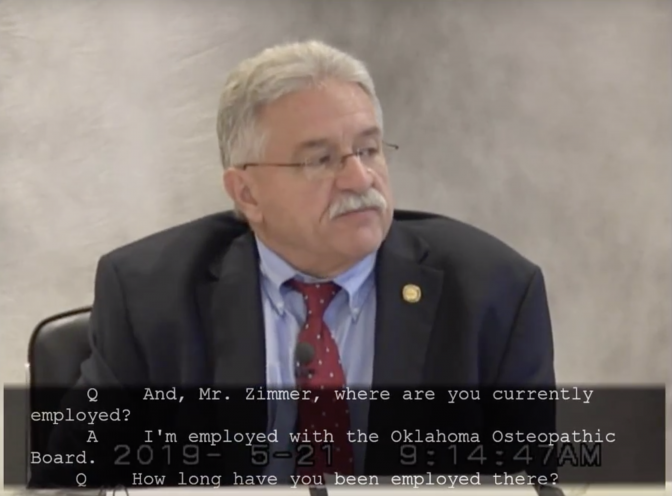

The court heard video testimony from Richard Zimmer, chief investigator for the Oklahoma State Board of Osteopathic Examiners. The board is responsible for licensing and disciplining 2,500 Oklahoma doctors.

Zimmer said that there were no written guidelines or common standards for handling an improper opioid prescribing complaint against a doctor.

“Every case is different. So there’s a different set of circumstances in every case, and each one of those is looked at by that case review committee,” Zimmer said.

He told the court that the board is ‘complaint-driven’ and that complaints must be sent by mail. Zimmer said he then looks through them to see if any are an emergency situation, and if not, sends them on to the review committee, which he also sits on.

Jackie Fortier / StateImpact Oklahoma

Video testimony of Richard Zimmer, chief investigator at the Oklahoma State Board of Osteopathic Examiners played during the state’s lawsuit against opioid manufacturer Johnson & Johnson.

Zimmer also testified that there was no standard form of communication between the state osteopathic board and other agencies that do criminal investigations. Zimmer told the court that sometimes he finds out about doctors that the board oversees being arrested in the newspaper.

The Oklahoma Osteopathic Board did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

“I mean, it just seems a little more ad hoc then might be appropriate for a board that is supposed to be protecting the public,” said Corey Davis, a lawyer and deputy director at the Network for Public Health Law.

In the U.S., there isn’t much federal oversight of doctors, leaving complaint-driven state medical boards in charge of licensing and disciplining.

“The [United States Drug Enforcement Administration] can take away a person’s ability to prescribe controlled substances but they can’t take away your ability to practice medicine, only the state can do that,” Davis said.

Over the years, some Oklahoma doctors have been charged and found criminally liable for extreme opioid prescribing. But the lack of communication between agencies means that state medical boards across the country are relying on patients to complain, in order to know that there’s a problem.

“There needs to be some process other than just waiting for somebody to complain,” Davis said. “Because you’ve got to imagine that by that time, it’s probably too late.”

Doctors have become more aware of their role in overprescribing opioids, said Stefan Kertesz, addiction specialist professor of medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

“The simplest solution for a doctor concerned about their career is to take everybody’s dose down across the board or to announce that they will not care for anybody who is already receiving opioids, and that’s about 10 million Americans,” Kertesz said.

That can leave patients without a doctor at all. Rather than cracking down, Kertesz says that medical boards should support and counsel doctors who exhibit opioid prescribing red flags, but who aren’t breaking the law.

“Health is actually a more complicated thing, and protecting people is a more complicated thing than whether the pills are just too much or too little and we need to escape that paradigm,” he said.

But sending a trained health professional to help a physician change their entrenched prescribing practices would be very expensive. Oklahoma’s two medical boards get very little state funding, though that could change if the judge in the Johnson & Johnson case sides with the state.

The judge is expected to announce a verdict in the case in August.

Editor’s Note: A previous version of this story misspelled Stefan Kertesz’s name. The story has been corrected to reflect the correct spelling.