Michael Payne sorts through boxes of donated food at the end of the 2019 school year at Northeastern State University.

Michael Payne sorts through boxes of donated food at the end of the 2019 school year at Northeastern State University.

Oklahoma has slashed funding for higher education by over 25 percent since 2008. In response, each public university has raised tuition, but the cuts have had a disproportionate effect on the state’s 11 regional institutions and the students they serve.

At Northeastern State University in Tahlequah, the cost of a bachelor’s degree has gone up significantly in the last decade. The school has raised tuition and fees by 75 percent since 2008. At the same time, real household incomes have actually decreased in much of the NSU’s service area according to an analysis from the U.S. Census Bureau.

“With the disinvestment by the state, we’ve had to cover some of those costs with other revenue, and we’ve had to cut expenses significantly. We want to remain affordable but also have to meet the bottom line,” explained Dr. Steve Turner, who has served as NSU’s president since 2012.

“I think anytime you have a tuition increase it is an impediment for someone, and we do serve a lot of students that are quite poor,” Turner said.

While NSU’s administration slowed hiring and reduced class offerings, students tried to ease the burden of paying for school in other ways. In 2014 they started a food pantry that has since expanded into Rowdy’s Resource Room. It’s a place where any student can get free food, clothing, toiletries, school supplies and more.

“A lot of students struggle to pay for everything,” said Michael Payne, who oversees Rowdy’s Resource Room. “The Resource Room allows that spending that students were going to be doing on food to go to other things, most likely their tuition.”

The Most ‘Vulnerable’ Institutions

Dr. Turner believes the cuts to state funding have had a unique impact on regional universities like NSU because, unlike the University of Oklahoma and Oklahoma State University, they don’t have large endowments to fall back on.

Dr. Sandy Baum, a higher education researcher at the Urban Institute in Washington D.C., agrees.

“It’s true that those institutions are more vulnerable,” Baum said. “One piece of it is endowments, but also the flagship universities are much more likely to have the possibility of attracting students from out of state or international students who pay higher tuition. That can compensate to some extent for the loss of state funding.”

Baum also says regional universities tend to serve more “at-risk” students, who are more likely to fail or dropout. One of the factors that determines the likelihood of graduation is income. Low-income students graduate at lower rates.

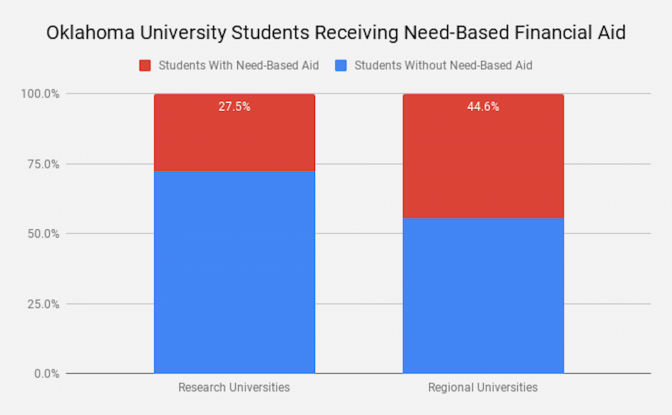

Nearly half of Oklahoma’s university students attend regional institutions. Data from the Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Education shows that compared to those attending OU and OSU, regional university students are far more likely to receive need-based financial aid, and they graduate at much lower rates. In 2018 the average six-year graduation rate for regional universities was 28 percent lower than the flagship universities. That graduation gap has persisted for the last ten years.

Data from the Oklahoma State Board of Regents show about 27 percent of students at research universities receive need-based financial aid versus over 44 percent at regional universities as of May 2019.

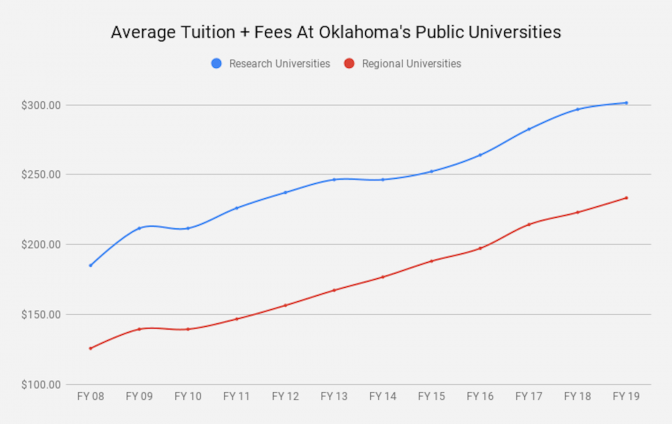

Regional university students have also faced the steepest tuition hikes over time. Tuition at those schools has increased by an average of 86 percent since 2008, compared to about 63 percent at OU and OSU.

Data from the Oklahoma University of Regents show that while regional universities remain less expensive than research universities, tuition and fees at regional universities have increased at a higher average rate over the last decade.

Reinvesting in Higher Education

There are good reasons for states to spend on higher education. Research shows people with bachelor’s degrees earn far more on average than those with just a high school diploma, and the future economy demands and more highly-educated workforce. In Oklahoma specifically, it is predicted that up to 70 percent of jobs will require education beyond high school by 2025.

As college costs have risen nationwide following the Great Recession, Baum believes policy discussions have focused too narrowly on price, especially when it comes to low-income students.

“We do know that at lower prices more low income students are going to enroll in college,” Baum said. The question of whether they’ll graduate is less clear.

“There is a lot of evidence that just giving people a thousand dollars off the price can have much less impact on their success, particularly for low-income students, than giving the money to the institution to provide them with better support services to succeed academically, to graduate and then to get a good job.”

Baum referenced a 2017 paper by Dr. David J. Deming of Harvard University and UC Berkeley’s Christopher R. Walters. The two researchers found that each additional dollar given to post-secondary institutions had a greater positive effect on degree attainment than price cuts.

Oklahoma lawmakers increased higher education funding this year by $28 million or roughly 3 percent– the largest appropriation increase in ten years–but that money is restricted to faculty salaries and research, so it cannot be used for support services. To put that figure in perspective, Northeastern State University alone receives $13 million less annually than it did a decade ago.