Alexis Stephens' son created a comic book to tell the story of his mom's addiction from his perspective.

Quinton Chandler / StateImpact Oklahoma

Alexis Stephens' son created a comic book to tell the story of his mom's addiction from his perspective.

Quinton Chandler / StateImpact Oklahoma

Quinton Chandler / StateImpact Oklahoma

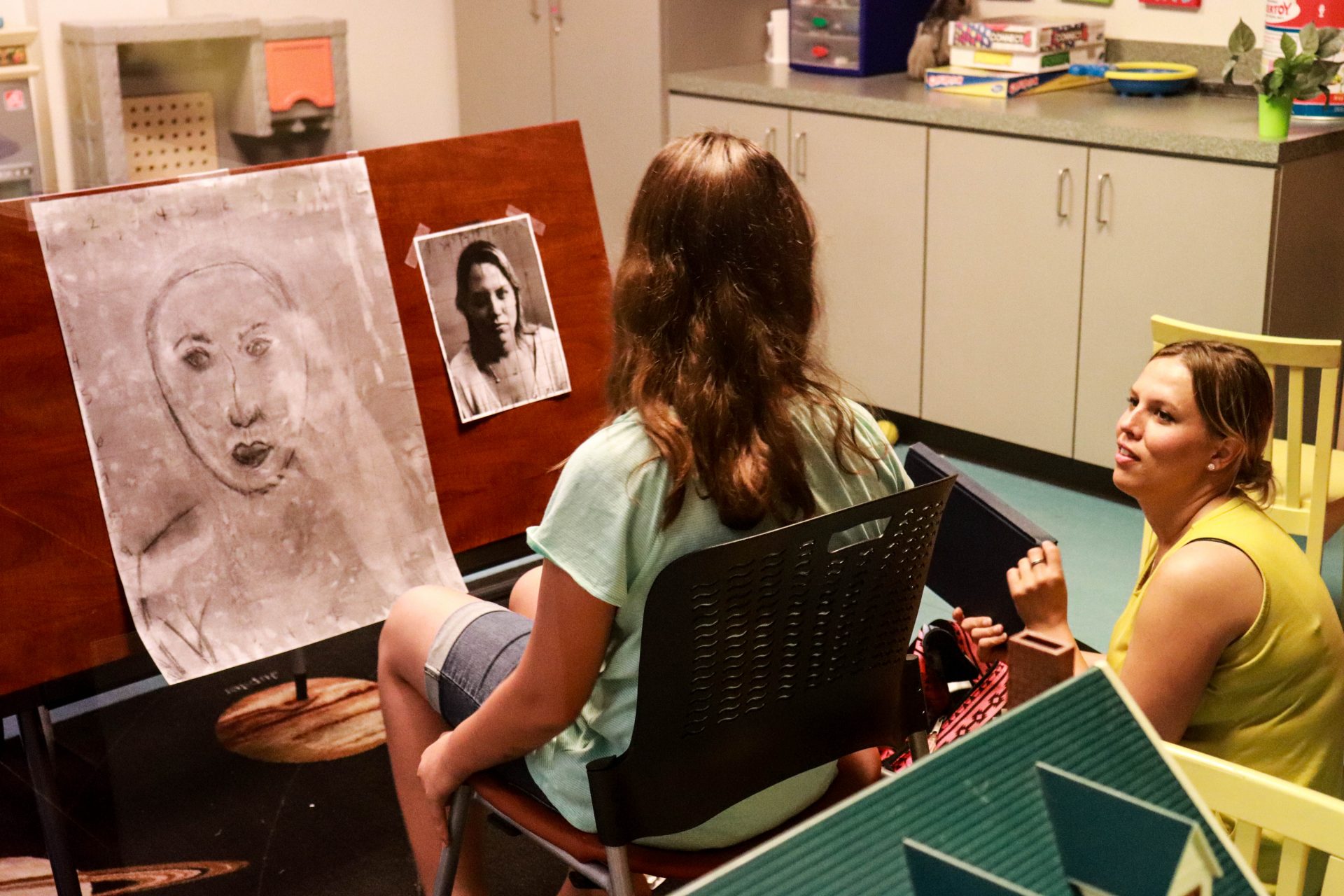

Sarah Sinkinson gets regular visits with her children while she completes the program at Women in Recovery.

It’s been three weeks since Sarah Sinkinson last saw her children and she’s ready for a visit from her daughter, Madeline. Sinkinson lights up as her daughter is escorted into a small visitation room and sits down at a desk opposite her.

Sinkinson is recovering from drug addiction. Mothers struggling with addiction often have a hard time making connections with their children. This can be especially challenging for moms facing criminal charges and the prospect of jail or prison time. Experts say rebuilding these relationships can help mothers overcome their addictions — and even steer their children off the path to prison.

Today, Sinkinson is helping her daughter with a charcoal drawing for art class. Her daughter says she hasn’t used charcoal before, so Sinkinson reassures her that it’s fun, but admits that she’s not very good at drawing eyes.

For years, Sinkinson came in and out of her children’s’ lives, abusing alcohol, marijuana, prescription pills and meth. Now, she’s part of Women in Recovery, a program managed by a Tulsa nonprofit that provides behavioral health and family services. Sinkinson usually visits with her three kids every two weeks.

Women in Recovery is a treatment and rehabilitation option Tulsa courts give some women arrested for crimes stemming from drug abuse. If Sinkinson graduates the program, she won’t have to go to prison. Sinkinson faces charges for possession of meth and paraphernalia, possession of a stolen vehicle, public intoxication and violating a protective order.

Women in Recovery is one of just a few non-government programs Oklahoma courts partner with to give women struggling with addiction an alternative to prison.

Oklahoma has the country’s highest female incarceration rate and state prisons are severely overcrowded. Eighty-five percent of women in Oklahoma prisons who responded to a 2014 study said they were mothers. Those numbers are a concern because experts and officials say children with parents in prison are overwhelmingly more likely to spend time in prison than other children.

Quinton Chandler / StateImpact Oklahoma

Amanda Gaddy is supervisor of Parenting and Children’s Services at Women in Recovery.

Amanda Gaddy is head of parenting and children’s services at Women in Recovery. She supervises Sinkinson and her daughter’s interaction from behind a two-way mirror in an adjacent room.

Children are often traumatized when they’re separated from mothers serving jail or prison time, Gaddy said. She hopes the recovery program helps prevent a generational cycle of incarceration by teaching struggling mothers to be parents.

Most of the women in the Tulsa program have been abusing drugs for 10 to 15 years, Gaddy said. “Most of them have never parented their children sober before,” she said, adding that many of the women didn’t get healthy parenting as children either, so they don’t have a model to use with their kids.

Gaddy and her staff teach the mothers parenting skills and concepts like the differences between discipline and punishment, appropriate activities for kids — and how mothers can meet their children’s emotional needs.

The visitation room is a space for the mothers like Alexis Stephens to put those lessons into practice before they begin actively parenting on their own. Inside a downtown studio apartment that’s a five-minute drive from Women in Recovery, Stephen’s 9-year-old son Carson is asleep in the living room after getting home from camp. Addison, her 2-year-old, is watching television.

“She loves cartoons,” Stephens said. “She loves to sing-along, she loves to sing.”

Stephens is a Women in Recovery graduate. She has a job and full custody of both her children. Before the program, she couldn’t have imagined this life. In 2016, Stephens was homeless. Her son was living with his grandmother, and she gave birth to her daughter in jail. She says Women in Recovery was her only chance to stay out of prison.

“We took a lot of classes on recognizing our addiction, our triggers,” Stephens said.

Quinton Chandler / StateImpact Oklahoma

Alexis Stephens earned full custody of her two children after graduating from Women in Recovery.

When her parental visits started, Stephens had to deal with her son’s anger for the first time. He was angry because, for years, Stephens says she neglected him. He was happy living with his grandmother and didn’t want to leave.

Stephens’ son went through therapy with the same nonprofit that manages Women in Recovery. He learned to cope with his anger and even created a comic book about a character named Firestrike — a hero born into a superhero family.

Stephens has a professionally bound copy of the comic the staff at Women in Recovery gave her as a graduation present. She flips through the pages and explains how the story relates to real life.

Her son is Firestrike. Firestrike’s mom, Flamer, is a superhero who loses her powers when a thief named Addiction steals them. The mother recovers and teams up with Firestrike to fight Icy Waters, a villain who represents the negative emotions Carson struggled with in real life. The hero learns that he is stronger when he fights with his mom.

“He talks about the healing powers of his mom,” Stephens said, her eyes watering and voice shaking. “There’s a page that says, ‘I got you,’ because that’s what I always tell him.”

In the end, Firestrike and Flamer make headlines in the news for beating the bad guy together.

It turns out eyes aren’t the only hard thing to draw with charcoal. Sarah Sinkinson is showing her daughter a trick to learning how to draw feet.

Sinkinson is working toward becoming her own superhero. She says battling personal villains on the way to recovery has been hard, but getting to see her kids gives her motivation to keep fighting. No matter what happens in the future, she plans to be honest with her kids about her problems and struggles.

“You have to keep the kids safe first, but longterm it’s so damaging for a kid to just stop talking to their mom,” Sinkinson said.