Researchers may have found deep, previously unmapped faults that could be a source of Oklahoma’s earthquake uptick

-

Joe Wertz

Previously unmapped faults in Oklahoma could be contributing to an intense uptick in earthquakes triggered by oil-field wastewater disposal, a new study suggests.

Scientists have linked thousands of earthquakes to the energy industry practice of pumping oil-field waste fluid into underground disposal wells in recent years, but the new research helps explain why much of the shaking doesn’t line up with maps of known faults, most of which detail fault formations within a mile of the surface.

“The problem is the earthquakes are happening from about 1 mile down to about 5 miles down,” said U.S. Geological Survey research geophysicist Anaja Shah, who led the research.

Oklahoma fault maps are built primarily with data describing surface and sedimentary rock layers that paint an incomplete picture of fault formations in a deep layer of granite, known among geologists and oil drillers as “basement rock.”

This granite rock, which also underlies oil and natural gas deposits, has long been scrutinized as a breeding ground for earthquakes. Oklahoma’s first regulatory response to the quake boom included directing oil and gas companies ensure disposal wells weren’t drilled into granite, where scientists warned wastewater could agitate faults and trigger shaking.

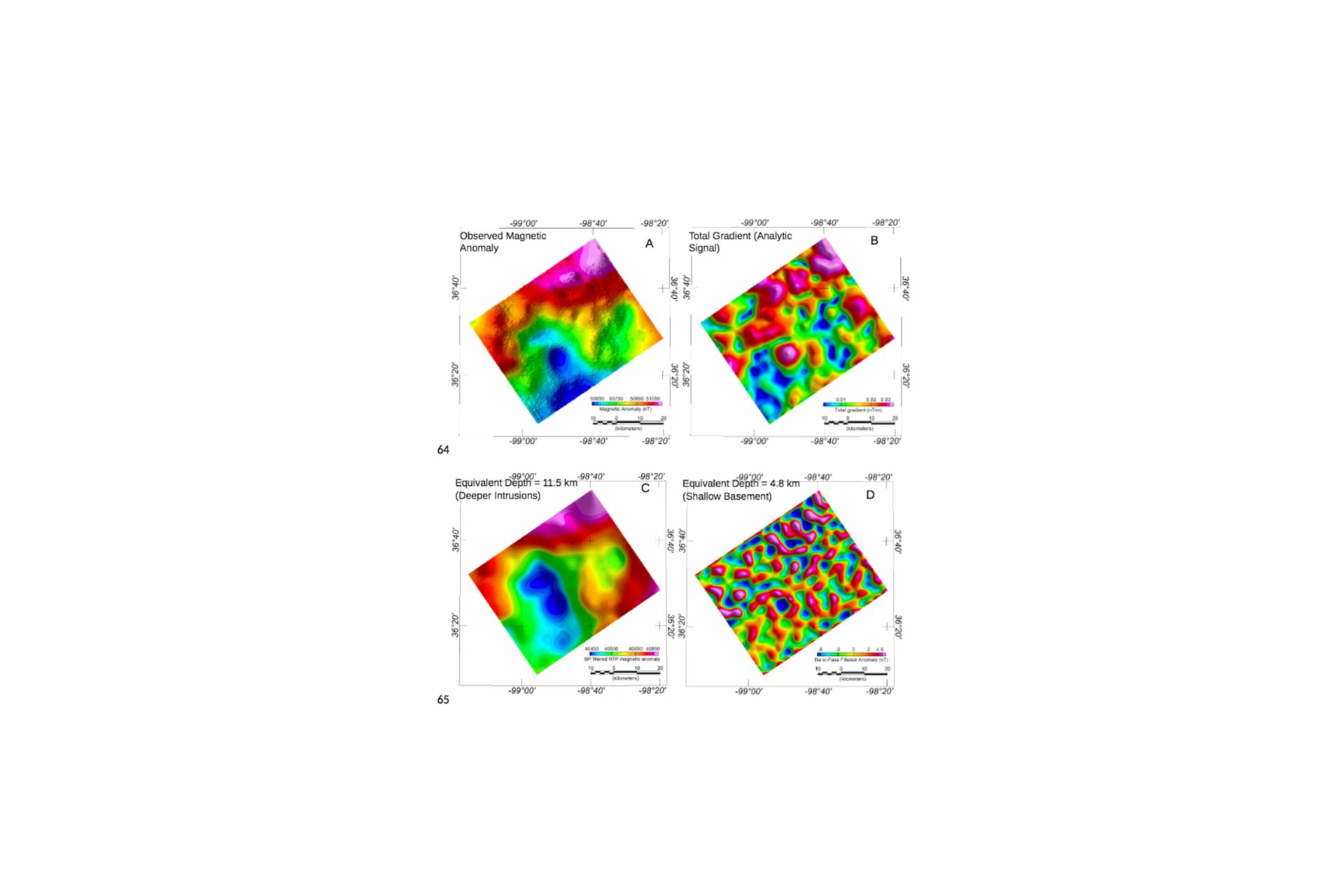

The new research, published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, is based on data collected in 2017 during a three-month aerial survey using planes outfitted with magnetic sensors.

Researchers used the data to identify possible faults in granite basement rock and to determine whether the findings corresponded with earthquake locations and known faults in shallower rock formations. The new data also suggest most faults in the deep granite layer are aligned in a particular direction — similar to wood grain.

“What’s especially interesting, which we didn’t know, is that that grain is actually different from the grain of the shallow rocks,” Shah said.

Researchers have to confirm the potentially new fault discoveries with other data, but Shaw says the orientation of faults in the deep granite layer also appears to be particularly well suited for slipping.

“When you add a bit of fluid injection, that’s probably what’s pushing it right over the edge,” she said.