About 82,000 children in Oklahoma lack health insurance, ranking the state 48th in the nation.

Jackie Fortier / StateImpact Oklahoma

About 82,000 children in Oklahoma lack health insurance, ranking the state 48th in the nation.

Jackie Fortier / StateImpact Oklahoma

Jackie Fortier / StateImpact Oklahoma

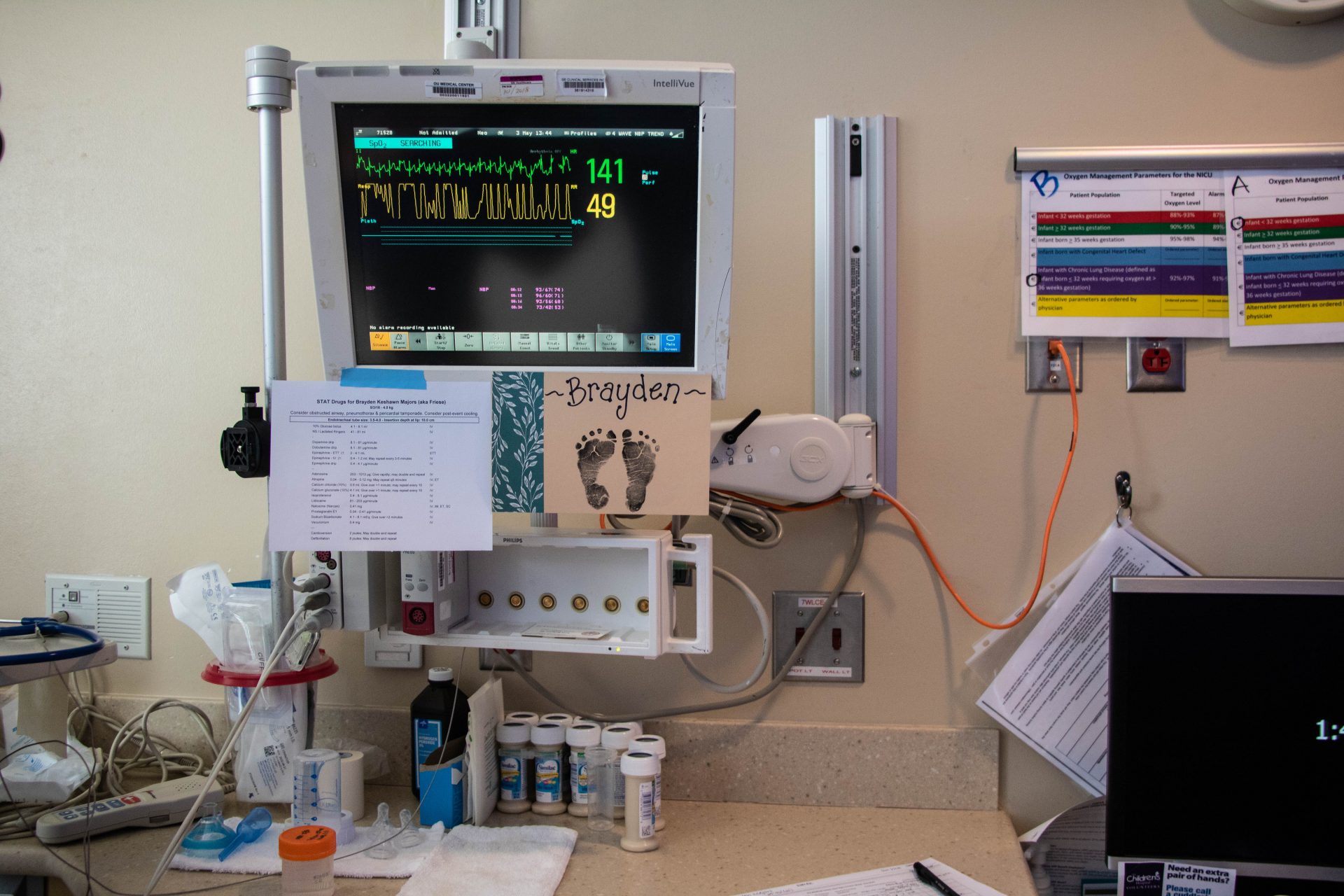

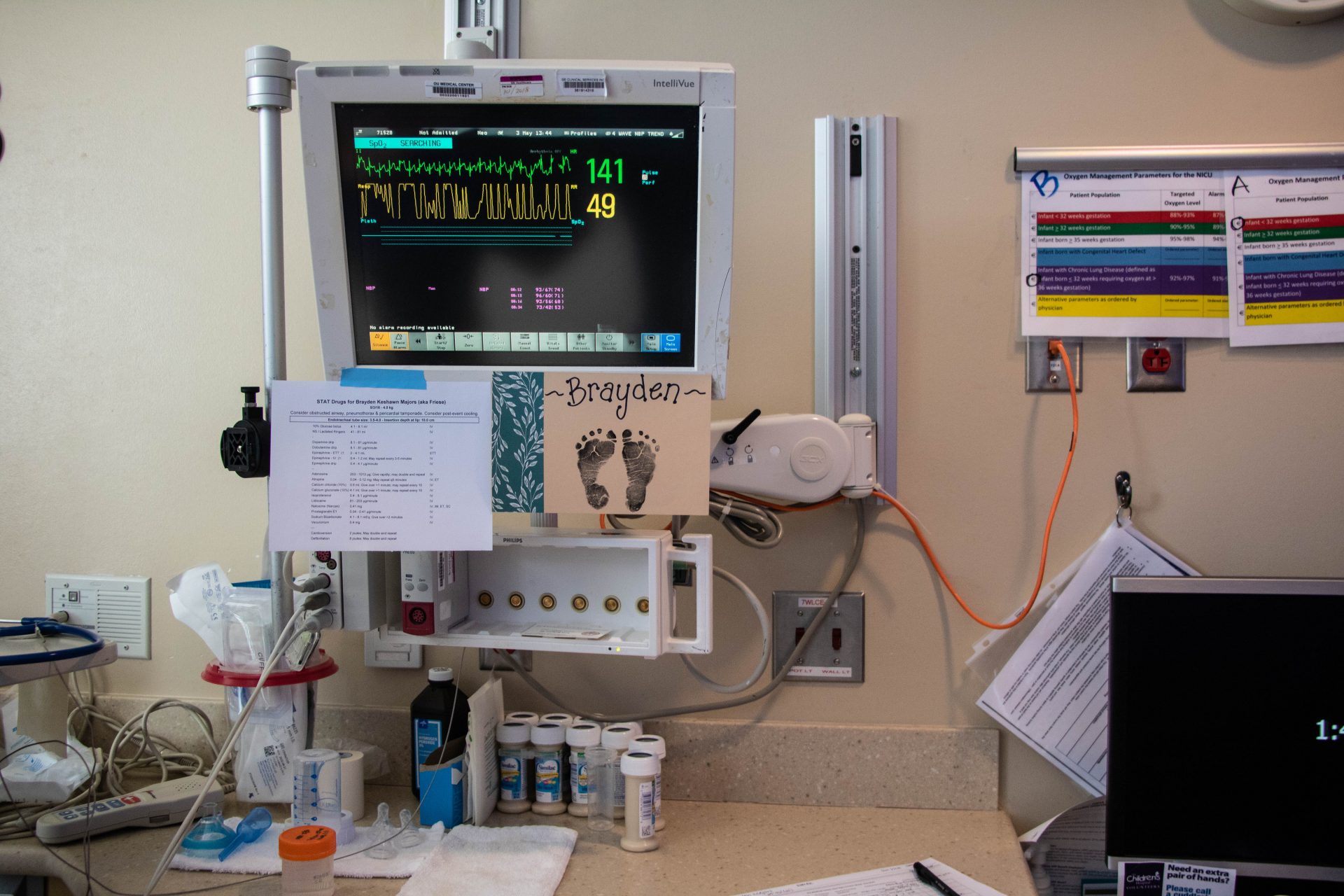

Tabitha Majors holds her son Brayden, at the neonatal intensive care unit.

Babies who begin life with a long hospital stay are especially vulnerable to secondhand smoke. That’s galvanized health officials at one children’s hospital to focus on laying aside stigma when they ask parents a simple question: ‘Do you smoke?’

One of those parents is Tabitha Majors, who has had a tough three weeks. She’s sitting in the neonatal intensive care unit at Children’s Hospital at the University of Oklahoma Medical Center in Oklahoma City, where her newborn son Brayden is recovering from surgery.

“He was close to dying at home. We had him home for 36 hours and he turned purple three times,” she said.

Brayden was born with a genetic condition that affects his jaw and hinders his breathing. Seeing her newborn on the medevac helicopter, headed from Elk City to the Children’s Hospital trauma center pushed her over the edge. She went back to her coping mechanism – cigarettes.

“He got on the helicopter, and I told my friend, ‘Give me a cigarette.’ I probably shouldn’t have, but I did,” Majors said.

She and other parents at the hospital are asked to fill out a form on tobacco use and if they’d like help from the Oklahoma tobacco quit line. Majors, who’s smoked since she was a teenager, answered yes.

That’s where hospital councilor Cheri Tennery comes in.

Babies that are born prematurely or have major surgery can spend weeks or even months at the hospital. The fragile infants may have underdeveloped lungs, or suppressed immune systems – issues aggravated by second-hand smoke. Tennery sets up consultations with parents who use tobacco and is careful not to lay blame or use scare tactics.

In a room off the main NICU, Tennery sits across the table from Majors and smiles encouragingly.

“I see that you filled out that you’re interested in a referral to the quit line, which is great – so tell me, what are your thoughts on quitting?”

“What made me want to quit is my son, he has breathing issues and all his respiratory stuff,” Majors said. “I know when I smoke it’s not good for him, it stays on my clothes and my hair, and it’s not good for him.

Majors tried quitting before, right after her son was born, but the stress of having a child in the NICU was too much, and she started smoking.

Jackie Fortier / StateImpact Oklahoma

Hospital councilor Cheri Tennery sets up consultations with parents who use tobacco and is careful not to lay blame or use scare tactics.

She’s not alone. A Centers for Disease Control report found that about 1 out of 10 expectant mothers in Oklahoma smoke. That’s a little worse than average. But focusing on mothers alone isn’t the answer, says Thomas Northrup, the associate director of the Behavioral Health and Addiction Research Program at the University of Texas Health Sciences Center in Houston.

“Particulate matter can actually stay on your breath for about 90 seconds after you finish a cigarette,” Northrup said. “So if you take your last drag and then immediately walk inside, you’re still exhaling what you drew into your lungs for the next minute and a half.”

He’s done numerous studies on tobacco use and NICU families. He says healthcare workers need to understand the stigma associated with smoking to get parents to open up.

“When we can communicate to them that hey, we understand you may not want to quit, but there are ways that you may be able to smoke that is less harmful to your child, I think parents are more receptive to that message,” Northrup said.

He says that most doctors offices may only ask about smoking and hand over a pamphlet. The Oklahoma program’s focus on conversations and screening makes a big difference.

“When we put caregivers in that position to read the information, that may inadvertently convey to them that it is less important than the topics we’ve discussed one-on-one or face to face,” he added.

The three-year-old program, funded by the Tobacco Settlement Endowment Trust seems to be working. More parents are filling out the form, and referrals to the tobacco quit line are up.

“There were mixed feelings about talking to families while they have a baby in the NICU because it is a high-stress time,” Cheri Tennery said. “What our data has shown, is that families are just as open at this point as they are at any other time.”

Oklahoma still has a high smoking rate — more than 20 percent — but that’s falling year by year.

But another form of nicotine is getting more popular. Ten percent of Oklahomans vape — the highest in the nation. Health experts worry young people might be more likely to grab an e-cigarette that tastes like bubblegum or crème brulee than a traditional cigarette.

Vaping could get even more popular. In July, the cost of cigarettes and little cigars will increase by $1 a pack in Oklahoma. Health officials worry people will choose cheaper e-cigarettes that don’t have a special tax.

The infant intensive care unit program is adapting. Hospital officials recently added vaping to the list of nicotine products they ask parents about.

Majors looks down at her son Brayden, who lies in a plastic bassinet at the NICU. She gently picks him up and holds him. The family is headed home soon, and the tobacco quit line will reach out within a week with counseling and free nicotine replacements.

Majors is adamant that this time, she’s going to quit.

“I refuse to watch my son struggle to breathe because I want to smoke a cigarette,” she said.