The U.S. Senate narrowly confirmed Scott Pruitt as administrator of the EPA in 2017. It was the latest step in a political career that has focused in large part on faith-based issues.

J. Scott Applewhite / AP

The U.S. Senate narrowly confirmed Scott Pruitt as administrator of the EPA in 2017. It was the latest step in a political career that has focused in large part on faith-based issues.

J. Scott Applewhite / AP

J. Scott Applewhite / AP

The U.S. Senate narrowly confirmed Scott Pruitt as administrator of the EPA in 2017. It was the latest step in a political career that has focused in large part on faith-based issues.

The Sunday before Scott Pruitt’s confirmation hearing to run the Environmental Protection Agency, Pruitt stood on the stage of his hometown church, bowed his head, and prayed.

“I stand on a platform today with a man of God who’s been tapped to serve our nation,” said Nick Garland, the senior pastor at First Baptist Church in Broken Arrow, Okla.

“It’s an honor for the kingdom of God to have a man of God who’s going to fill that role,” said Garland. “We wanted to pray for you today, and ask God to bless you.”

The congregation at First Baptist, which is part of the Southern Baptist Convention and has a membership of some 4,500, has counted Pruitt as a member for nearly three decades. Pruitt is also a deacon at the church.

Throughout his career, he has relied on the church for both spiritual and political strength.

While Pruitt is probably best known now for his aggressive attempts to roll back Obama-era environmental regulations — and perhaps for the increasing number of investigations into alleged ethical misconduct — much of his career has been driven by faith-based issues like abortion and religious freedom.

Pruitt and the EPA did not respond to several requests for comment over nearly two months, including a four-page list of questions from NPR. But an examination of Pruitt’s public statements and his record shows that says his faith continues to inform his views of the environment and climate change.

Pruitt is originally from Kentucky, and went to the University of Kentucky on a baseball scholarship. He played second base and, according to E&E News, his fellow players nicknamed him “The Possum.” (“I thought he looked like a possum,” the team’s shortstop, Billy White, explained.)

Pruitt later transferred to Georgetown College, a Baptist school in Georgetown, Ky., before moving to Oklahoma to attend the University Of Tulsa College Of Law.

After graduation, Pruitt got his first client, a woman named Judith Lyn Whittington.

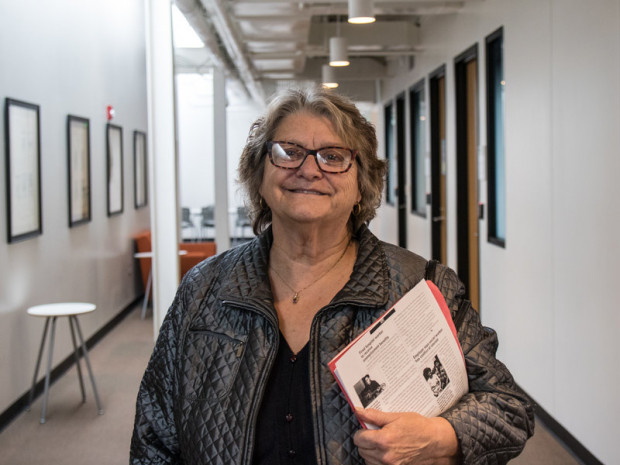

Joe Wertz / StateImpact Oklahoma

Judith Lyn Whittington was Scott Pruitt's first legal client. She sued her employer, Oklahoma's Department of Human Services, arguing that the state was infringing on her religious freedom.

In the early 1990s, Whittington sued her employer, Oklahoma’s Department Of Human Services, alleging religious discrimination. Whittington had converted to Christianity later in life, and was active in her church’s crisis pregnancy center, which counsels women not to have abortions. (In general, such centers can be controversial, and medical groups and abortion rights activists have accused some centers of misleading women.) Whittington also held a Bible study at her home.

“I was a fairly new Christian,” she says. “It was very important to me to be able to do the things that I thought God was leading me to do.”

Then came the conflict with her employer.

Whittington had become friends with a woman through her work at the crisis pregnancy center. One day, she helped the woman and her young daughter move out of their living situation.

Trouble arose, because the woman was also a client of the Department of Human Services.

Supervisors at the department disciplined Whittington, because they said she was blurring the lines between her volunteer work for the crisis pregnancy center in her off-hours, and her work for the state agency.

Whittington says she got a call from one of her supervisors, who told her, “You’re not allowed to have any contact after hours with DHS clients or potential clients.”

As a result, Whittington decided to end her Bible study, and stopped volunteering with the crisis pregnancy center.

Eventually, she got in touch with the Rutherford Institute, a conservative nonprofit, which connected her with Scott Pruitt.

“He was a young lawyer, but he was a go-getter,” says Whittington. “I mean he started working on [the case] that day. He was excited about it.”

And Pruitt’s excitement, Whittington says, came from his genuine dedication to religious freedom.

“He saw it as: This is what she truly believes and she has the right to do it,” she says.

The case ultimately resolved because of a national religious freedom law signed by President Clinton. That law prompted Oklahoma to change its employment policies, and the state settled with Whittington. She was able to resume her work with the crisis pregnancy center and restarted her Bible study.

Whittington still credits Pruitt with reaching the settlement.

“He was there, a young attorney, when I needed an attorney so badly,” she says.

The case also stuck with Pruitt. He later featured Whittington in a campaign ad, where he says the case sparked his interest in serving as Oklahoma’s attorney general.

“He was so honest, he was so kind, and he was so on fire for God’s work,” Whittington says in the ad.

On one end of the wall are four bricks, one for each member of the Pruitt family.

Joe Wertz / StateImpact Oklahoma

A brick wall at First Baptist Church in Broken Arrow, Okla., is inscribed with the names of people who donated to the church's relocation. Among the names is Scott Pruitt.

Over the years, Pruitt and Garland have spent a lot of time together, though Pruitt has had fewer opportunities now that he’s in Washington. Garland says Pruitt will still call or text him when he’s got a big meeting and will ask Garland to pray for him. Garland told Mother Jones that he recently went to a private reception at the EPA with Pruitt.

Soon after Pruitt came to Oklahoma and around the time of the lawsuit he joined First Baptist Church in Broken Arrow, a suburb just outside Tulsa.

Pastor Nick Garland describes Pruitt as an active and faithful member of the church, who has been involved in Sunday school teaching and eventually became a deacon.

Outside the church’s worship center, where roughly 2,500 people gather each Sunday, there’s a brick wall inscribed with the names of people important to that church and who donated to the church’s relocation.

Pruitt is also a former trustee with the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary and he says his faith forms the foundation of his politics.

“A Christian worldview means that God has answers to our problems,” said Pruitt, according to the seminary’s website. “And part of our responsibility is to convey to those in society that the answers that he has, as represented in Scripture, are important and should be followed, because they lead to freedom and liberty.”

The Southern Baptist Convention, as well as Garland and Pruitt, oppose same-sex marriage, abortion rights and transgender rights.

In one 2016 sermon, Garland criticized the Obama administration’s guidance on transgender students and bathrooms.

“In this generation, where people are trying to decide what they believe about sex,” he said, “it’s because we’ve forgotten the one who made them male and female. In a generation, where we’re not sure if God created, because we’ve propagandized evolution, we’ve forgotten that in the beginning, God.”

(Pruitt also sued the Obama administration over that guidance, calling it “Obama’s Transgender Power Play” in The Wall Street Journal.)

On the environment, Garland is also skeptical of the scientific consensus, which has argued for urgent action to prevent the potentially disastrous consequences of climate change.

Joe Wertz / StateImpact Oklahoma

A brick wall at First Baptist Church in Broken Arrow, Okla., is inscribed with the names of people who donated to the church's relocation. Among the names is Scott Pruitt.

“Let’s be a little more cautious,” Garland says. “Let’s not overreact on supposition.”

On climate change, Pruitt has argued for a government-sponsored debate on climate science and the potential effects of greenhouse gases. And he recently told the Christian Broadcasting Network that he believes God blessed humanity with natural resources like coal and oil so that people may use them.

“The biblical world view with respect to these issues,” he said, “is that we have a responsibility to manage and cultivate, harvest the natural resources that we’ve been blessed with to truly bless our fellow mankind.”

Pruitt was elected to the Oklahoma State Senate in 1998, and an NPR review of legislation he sponsored shows a strong focus on faith-based issues.

Early on, he sponsored a state Religious Freedom Act. He also sponsored legislation to provide state funding to faith-based organizations working in juvenile justice.

Most years he was in the state Senate, he also sponsored legislation to restrict abortion, including what’s known as an “informed consent” bill. Such bills mandate language that doctors have to use before performing an abortion.

“[Women] need to know that there’s a link with breast cancer,” Pruitt said in 2003. “They need to know that there’s a risk with infertility, they need to know that there are emotional risks attendant with abortion procedures.”

Leading medical groups say all of those claims are either false or misleading.

While voting for another abortion restriction measure in the Oklahoma Senate, Pruitt said, “I’m voting to say that an unborn child from the moment of conception should be considered a legal person under the 14th Amendment.”

Such a move would effectively criminalize abortion.

Around this time, according to filings NPR obtained from the Oklahoma Ethics Commission, Pruitt served on the board of a crisis pregnancy center in Tulsa.

Pruitt also supported a bill called the Teacher Protection Act, which would have required textbooks in Oklahoma to add a 251-word disclaimer about Darwin’s theory of evolution. That disclaimer included this line: “any statement about life’s origins should be considered as theory, not fact.”

In a 2005 radio interview first unearthed by Politico, Pruitt said, “there aren’t sufficient scientific facts to establish the theory of evolution.”

When Pruitt became Oklahoma’s attorney general after the 2010 election, he continued to pursue many of these priorities. He fought a move by Oklahoma’s Supreme Court to remove a public display of the Ten Commandments at the state Capitol, and he joined a lawsuit against the federal government over the Affordable Care Act’s contraception mandate.

“Our Founding Fathers established a system to protect us from this type of coercive federal infringement on religious liberty,” Pruitt argued.

The increasing number of ethics investigations into Pruitt’s actions as EPA administrator have raised speculation that President Trump may fire him.

In the last century, no presidential Cabinet has seen more turnover in its first year than this administration.

Pruitt has argued that the criticism is partisan, and says that his opponents will “resort to anything” to stop his regulatory rollback at the EPA.

On Tuesday, the agency confirmed that two high-level EPA employees — Albert Kelly and Pasquale Perrotta — had left the agency.

Whatever happens, it has been widely reported that Pruitt has ambitions for other positions, whether senator or governor of Oklahoma, or even U.S. attorney general.

His record on faith-based issues suggests he would continue to pursue those priorities in other offices.

For now, Pruitt joins a weekly Bible study with other members of the Trump Cabinet. He recently told CBN News, “it’s such a wonderful thing” to pray with “a friend, a colleague, a person who has a faith [and] focus on how we do our job.”

Tom Dreisbach is a producer with NPR’s Embedded