Henry Weathers had a heart transplant 10 years ago, when he was five years old. His parents are worried he may not get another, due to bias.

Jackie Fortier / StateImpact Oklahoma

Henry Weathers had a heart transplant 10 years ago, when he was five years old. His parents are worried he may not get another, due to bias.

Jackie Fortier / StateImpact Oklahoma

Jackie Fortier / StateImpact Oklahoma

Henry Weathers had a heart transplant 10 years ago when he was five years old. His parents are worried he may not get another, due to bias.

Shiny red hearts decorate the tables at a restaurant in Moore. It looks like a Valentine’s Day party, but tonight the decor is literal: It’s the 10-year anniversary of Henry Weather’s new heart.

“You have to realize that Henry’s heart transplant was our seventh major surgery,” said Henry’s dad, Ned Weathers. “When he was born the umbilical [cord] was cut, he turned purple and off to the races we went.”

Henry was born without the lower left chamber of his heart and was just 3 days old when he had his first surgery. By the time Henry was 5 years old, he was listed for a heart transplant. His family got the call on Valentine’s Day and flew to St. Louis for the procedure.

Henry’s mom Erin Taylor says her son, now 15, is very healthy, despite undergoing more than 30 surgeries and being on two post-transplant immunosuppressant drugs that leave him vulnerable to infections.

“It’s probably still a reality that I’m going to bury my son, but when he was born a surgeon told me, ‘You should feel really lucky if he makes it to 5 or 6 years old,’” Taylor said.

Organ transplants don’t last forever. Eventually, the body rejects the organ or it becomes inefficient. As Henry gets older, his parents are starting to worry. The heart condition starved Henry’s developing brain of oxygen. The resulting damage contributed to a developmental disability with which Henry now lives.

“One of two things will happen, he will die, or he will be re-transplanted, those are the realities of our life,” Taylor said. “People began to send me stories saying hey, do you know that sometimes they deny people because of an IQ score or because of how the doctor perceives their cognitive level?”

More than 116,000 people across the U.S. are on the organ transplant list, and 20 people die each day waiting for a transplant.

Surgical teams add people to the list by considering numerous factors thought to determine an organ’s success or failure — things like a candidate’s age, ability to pay medical bills, family support, whether or not they smoke. There is also a mental assessment, but the biggest factor is how long an organ candidate has left to live.

That life-and-death decision interested David Magnus, director of the Center for Biomedical Ethics at Stanford University Medical School. He surveyed 50 pediatric transplant programs in 2008 and found that 43 percent always or usually considered developmental delays like Henry’s in deciding whether to list someone as eligible for an organ.

Magnus just finished another survey, where he found that “adult programs are even more likely to hold developmental delay into account as a contraindication than pediatric programs.”

Aside from a few restrictions under the Americans with Disabilities Act, a transplant team of doctors, nurses and psychologists have almost full autonomy to decide who gets life-saving organs. As a result, there’s a wide variation from program to program.

“Our data shows that it’s pretty clear, that in general, there is a bias, and that some individuals that should be transplanted aren’t being listed,” Magnus said. “It shows that there is a justice problem because the same kids are going to get listed at some places and not others.”

Mangus says the decision-making process needs to be more equitable. He recommends a screening tool developed at Stanford that standardizes the evaluation process.

“The real solution is not to just say, ‘You shouldn’t discriminate,’ because that doesn’t help, I think what we need better objective tools for the psychosocial assessment process so that when people are making those determinations, they are making them as evidence-based as possible,” he said.

States are increasingly adopting new policies to manage organ transplant eligibility.

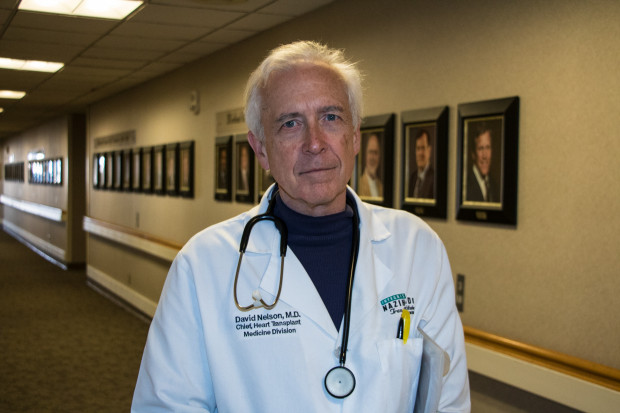

Lawmakers in Ohio are debating a bill that would make transplant discrimination illegal. In February, Kansas became the sixth state to have passed similar bipartisan legislation. No such measure is under consideration in Oklahoma. But David Nelson, chief of heart transplant medicine at INTEGRIS Baptist Medical Center in Oklahoma City, doesn’t think more government regulation is the answer.

Jackie Fortier / StateImpact Oklahoma

David Nelson, chief of heart transplant medicine at INTEGRIS Baptist Medical Center in Oklahoma City.

He says any patient’s support and home life is taken into account, no matter their IQ.

“We [surgical teams] are strongly motivated to consider any risk factor as just a risk factor because you’re expected to have volume and good outcomes,” he said. “That alone is a reason why individuals that have neurodevelopmental delay, at least in the adult community, I don’t think it’s an issue.”

Nelson says he has successfully transplanted two adults who were intellectually disabled in his career and says the team simply looked at their overall health and ability to take anti-rejection drugs.

Almost 60 percent of Oklahomans are registered organ donors, which is higher than the national average, but disability advocates are pushing for federal clarification of the Americans with Disabilities Act since so many people travel to different states to get transplants. A letter urging action was submitted to U.S. Department of Health and Human Services by 30 lawmakers in 2016. So far, nothing has changed.

“We deem them not worthy of an organ, and yet they can be organ donors,” said Henry’s mom Erin Taylor.

Henry’s parents know that someday, he’ll need a new heart. When that time comes, they want the surgical team to see Henry, not his IQ score.

“If you’re basing your entire decision on a cognitive score, on whether or not he understands Algebra and some basic concepts, you can do better and we deserve to do better for people like this,” Taylor said.