Baby Jacob weighs 7.14 pounds - some infants aren't as lucky.

Jackie Fortier / StateImpact

Baby Jacob weighs 7.14 pounds - some infants aren't as lucky.

Jackie Fortier / StateImpact

Jacob is just a few hours old when registered nurse Amy Burnett begins one of the simplest measurements to tell if a newborn is healthy — their weight.

“You want to make sure that they are naked, they have no diaper, and you bring him to the scale,” she says as she removes his tiny Pampers.

She gently picks him up, confidently balancing his body on her forearm like a football. Her purple gloved fingers encircle his neck as she hits a button on the scale, which beeps loudly, zeroing it out.

He squirms as she places his head toward the top of the plastic rim.

“Now you let it think,” she says gazing at the newborn.

This data are key. Unlike height, a baby’s weight can impact their future. Think of birth weight like Goldilocks. Not too big: That can cause health problems; not too small: Babies should weigh more than 5 and a half pounds.

A few seconds later, the scale makes another loud beep. His weight displays in red digits: 7.14 pounds.

Baby Jacob is just right.

“He’s doing great,” Burnett says.

Why pay such close attention to how much babies weigh at birth?

Sharyl Kinney, an assistant professor at the University of Oklahoma’s College of Public Health, says babies born at less than 5 and a half pounds have a higher risk of death and are more likely to have developmental disabilities later in life.

”They’re more likely to have psychomotor problems, to have failure in school and to have health problems,” she says.

About 7.8 percent of babies born in Oklahoma are low birth weight, which translates to roughly 4,000 of 50,000 annual births, Kinney says.

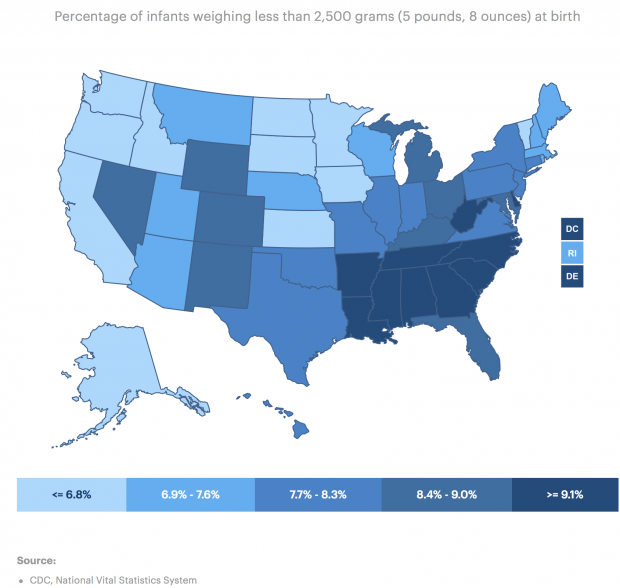

CDC, Center For Vital Statistics

More than 7 percent of babies are born at a low birth weight in Oklahoma in 2017.

Many of those low-weight births are considered preventable; the babies don’t have a significant health problem, so their weights could have been improved by outside factors, like money.

“Birth outcomes, including low birth weight, is a health indicator that is very sensitive to poverty,” says Kelli Komro, a professor at the Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University in Atlanta.

Komro is one of the authors of a study published in the American Journal of Public Health that looked at how changing the minimum wage in different states over three decades affected birth weights.

“Our estimate is that if a state would increase the minimum wage by $1 above the federal minimum wage, that would lead to one to 2 percent fewer low-birth-weight births,” she says.

That means if Oklahoma were to raise its minimum wage by $1, up to $8.25 per hour, as many as 80 babies a year could weigh more at birth. That would decrease the likelihood that they would need special education in school or grow up with other health issues — both of which could save the state a lot of money down the road.

Changing the minimum wage affects women the most. That’s because, in Oklahoma and many other states, women make up two-thirds of minimum wage earners.

Komro says other researchers have found that increasing the minimum wage leads to “increased access to prenatal care and reduced smoking among mothers. It could also reduce a mother’s stress, and we know that reducing stress would be beneficial for birth outcomes.”

Legislators in some states are starting to address the link between wages and newborn health outcomes. Komro says a few policymakers have requested data from her team, wanting to know how exactly raising the minimum wage would help kids in their state. Oklahoma officials have not requested data.

“Our hope is that policymakers will take the health effects of these policies into consideration in their debates,” she says.

In 2011, the Oklahoma state health department launched programs to increase the number of full-term pregnancies, and Oklahoma’s birth weights are improving. But health officials are reluctant to push for more. They say advocating for a change to the minimum wage — even if research says it might help — isn’t their job: That’s up to the Legislature.