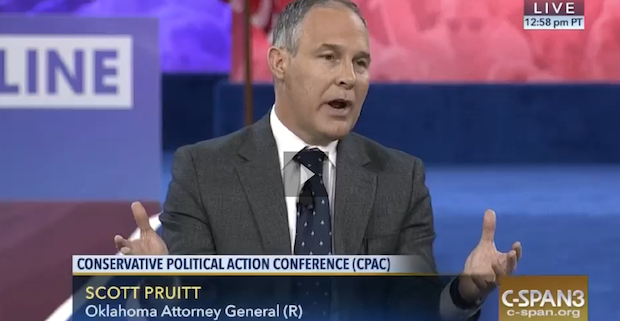

Oklahoma Attorney General Scott Pruitt speaking about energy self-sufficiency at the Conservative Political Action Conference in March 2016.

American Conservative Union / C-SPAN

Oklahoma Attorney General Scott Pruitt speaking about energy self-sufficiency at the Conservative Political Action Conference in March 2016.

American Conservative Union / C-SPAN

American Conservative Union / C-SPAN

Oklahoma Attorney General Scott Pruitt speaking about energy self-sufficiency at the Conservative Political Action Conference in March 2016.

President-elect Donald Trump’s nominee to run the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Oklahoma Attorney General Scott Pruitt, walked back a legal fight to clean up rivers polluted by chicken manure after accepting tens of thousands of dollars in campaign contributions linked to the poultry industry, campaign and court records show.

A report by the nonprofit Environmental Working Group verified by StateImpact shows at least $40,000 for Pruitt’s 2010 campaign was contributed by executives of poultry companies and lawyers of firms representing the companies named in a high-profile pollution lawsuit filed by his predecessor Drew Edmondson.

Pruitt declined requests for comment.

“Scott Pruitt’s antipathy for holding polluters accountable in his own state is a bad sign for things to come across America if he’s given the reins at the EPA,” EWG President Ken Cook said in an emailed statement. “The EPA’s job is to protect public health, not let industry off the hook for polluting our rivers and drinking water.”

The 2005 lawsuit against Tyson Foods and other poultry companies was filed to stop chicken manure from polluting the Illinois River. The runoff was linked to elevated phosphorus and nitrate levels that fueled algae blooms in ponds and waterways throughout the Illinois River watershed in Oklahoma and Arkansas.

Arguments in the lawsuit were concluded before Pruitt took over the AG’s office, but the judge has not issued a ruling. After his election as AG, Pruitt helped broker a third-party study of water quality in the Illinois River, but has not pushed for a ruling, court records show.

Residents in eastern Oklahoma tell the New York Times they’re frustrated by the lack of progress on the chicken manure lawsuit:

Phosphorus levels have declined considerably — a total of about 70 percent between 1998 and 2015 — but the largest reductions took place before Mr. Pruitt became attorney general, as wastewater treatment plants have been upgraded and more poultry farmers have shipped chicken waste for proper disposal. Still, the levels remain far above the state standard and the decline in pollution has been slower than some hoped.

“I want an attorney general — and a head of our E.P.A. — who is not averse to protecting Oklahoma’s most outstanding waterways,” said Ed Brocksmith, who is a co-founder of a group called Save the Illinois River.

The Environmental Working Group’s report comes just days before Pruitt’s confirmation hearings before the U.S. Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works. Pruitt has built much of his conservative political brand on fighting the federal government — the EPA in particular. Pruitt has filed and joined scores of lawsuits to block EPA rules on mercury, regional haze from coal-fired power plants and President Obama’s signature Clean Power Plan.

Environmental groups are stepping up opposition to Pruitt for casting doubt on the science of climate change and his close ties to the fossil fuel industry, which has contributed generously to his political campaigns. A 2014 investigation by the New York Times found that Pruitt was signing off letters to federal regulators drafted by industry lobbyists.

During his tenure in the Oklahoma AG’s office, Pruitt dismantled the office’s Environmental Protection Unit and created a new Federalism Unit dedicated to battling the federal government “when it has overreached its authority and encroached on the state’s ability to craft its own solutions as provided under the law.”

Pruitt says the AG office’s environmental enforcement continued under the authority of a different unit, though court records and state financial data suggest environmental enforcement hasn’t been a top priority for the Tulsa Republican.