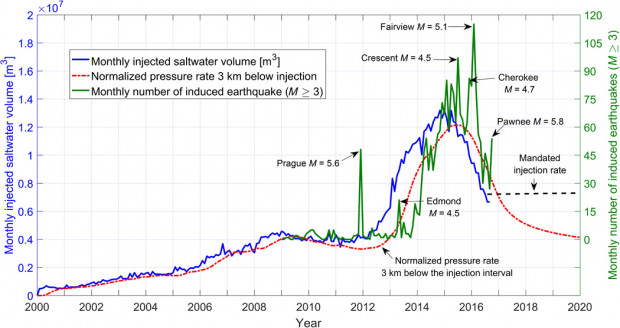

Monthly wastewater injection into disposal wells in the Arbuckle formation from 2000 to July 2016. A team of Stanford scientists found earthquake rate changes follow changes of the injection rate with a time delay of several months.

Science Advances

Monthly wastewater injection into disposal wells in the Arbuckle formation from 2000 to July 2016. A team of Stanford scientists found earthquake rate changes follow changes of the injection rate with a time delay of several months.

Science Advances

Science Advances

Monthly wastewater injection into disposal wells in the Arbuckle formation from 2000 to July 2016. A team of Stanford scientists found earthquake rate changes follow changes of the injection rate with a time delay of several months.

Scientists may have a promising seismic forecast for Oklahoma over the next few years: A lot less shaky with a smaller chance for damaging earthquakes.

Newly published research bolsters a growing body of scientific findings linking the state’s earthquake boom and the underground injection of large amounts of wastewater from oil and gas production, but suggests the shaking could taper off after 2016.

In a paper published in the journal Science Advances, Stanford University geophysicists Cornelius Langenbruch and Mark Zoback built a new statistical model that shows earthquake activity slowing as wastewater injection is reduced.

That’s good news, because Oklahoma’s injection rates started dropping significantly in early 2015 due to low oil prices and continued to slow due to efforts from state regulators to limit the amount of wastewater the energy industry pumps into disposal wells in quake-prone regions of the state, the scientists write:

On the basis of our results, the mandated saltwater injection rate reduction in 2016 was an effective step in mitigating the seismic hazard associated with the occurrence of triggered and induced earthquakes in Oklahoma…

Science Advances

Click here to read about the research by Stanford University geophysicists Cornelius Langenbruch and Mark Zoback.

The research also suggests a threshold at which the amount of injected wastewater is likely to trigger earthquakes. Langenbruch and Zoback write that it should be possible to inject a “limited amount” of wastewater into underground formations without it causing faults to slip.

The findings could help the U.S. Geological Survey fine tune the maps it creates to estimate earthquake hazards for public safety officials, building designers and the insurance industry. Until recently, that hazard program was focused on long-term risks posed by naturally occurring earthquakes, but the new research could help forecast “the evolving short-term hazard by considering future saltwater injection rates,” the Stanford team writes.

The new research doesn’t rule out the possibility of larger, damaging quakes, like the record-breaking 5.8-magnitude quake that rocked Pawnee in September 2016 or the 5.0-magnitude temblor near Cushing, which forced the temporary shutdown of one of the nation’s largest crude oil storage terminals. Langenbruch and Zoback’s research, however, makes the case that if wastewater injection rates remain low, Oklahoma could return to its relatively non-shaky state within a few years.

Consequently, earthquakes could persist in some areas irrespective of the overall rate of injection. Additional localized saltwater injection rate reductions might be required to mitigate the residual risk in these areas. Increased injection of saltwater should be prevented in all the areas in Oklahoma that have experienced increased seismicity in the past few years.