Seven miles west of Bokoshe, in McCurtain, where the ash protrudes like an iceberg from a water-soaked pit, residents have complained about dust clouds, spurring two state notices alleging violations — one in 2011; the other last year. Some residents have hidden special hunting cameras in trees to expose what they believe to be improper ash disposal. Others remember similar troubles at a pit just east of Bokoshe, where the ash has hardened into gray mounds resembling the surface of the moon.

“You choked to death,” recalls Joy Arter, who lives a half mile from that pit and, for years, did not go outside without a mask because the ash dust “was so thick and smoldering.”

The Making Money pit began accepting coal ash in the late 1990s, whipping up dissent. By 2000, when operators officially applied for a permit, 44 Bokoshe residents had petitioned state regulators, objecting to the operation. At a public hearing, they expressed concern over “fugitive dust; ground water; surface water; [and] asthma,” according to a transcript.

The company, then named Making Money Having Fun, or MMHF, LLC, vowed to contain the ash and suppress the dust. In a 2000 letter, it assured the petitioners that “disposing of [coal] ash material in a safe manner … has advanced to ‘state of the art.’”

Waste generator AES, for its part, has portrayed coal ash as harmless, likening it to dirt. “They said you could put it on your peanut butter-and-jelly sandwich,” recalls Herman Tolbert, a rancher whose family has owned nearly 1,000 acres beside the mine pit for three generations.

AES declined interview requests from the Center for Public Integrity and did not respond to written questions. In a brief statement provided to the Center, the utility cited the dismissal of the class-action lawsuit filed on behalf of Bokoshe residents against it, the pit operator and others over the disposal at the pit, which, the utility says, “did not present facts that would prove Shady Point’s practices caused injury to any of the plaintiffs.”

The plaintiffs and their attorneys say they wanted the case heard in an Oklahoma state court and chose, for tactical reasons, not to present detailed allegations of their injuries while the case was in federal court. A federal judge ruled the residents’ lawsuit did not meet the technical requirements to allow them to try their case in state court.

The utility says “the environmental practices at AES Shady Point comply with all applicable environmental regulations.”

Operators of the pit, now named Clean Hydro Reclamation, did not respond to calls and emails seeking comment.

Joe Wertz / StateImpact Oklahoma

An oxygen concentrator and bottles of oxygen in the entryway of Susan Holmes' home near Bokoshe, Oklahoma.

‘Oxygen in use’

For years, people in Bokoshe saw the gray dust from the Making Money pit coat almost every surface in town. Gardens withered and crops died, residents say. Cows grew sick; calves were stillborn. Residents say ailments among their neighbors — from migraines to nosebleeds, heart conditions and respiratory problems — seemed to become commonplace.

Bridget Wood remembers visiting Bokoshe for the first time in 2009 and wondering why so many houses bore the same sign: “OXYGEN IN USE.” Canvassing the town, she met “all these people who were very sick,” she says, hooked up to oxygen, reliant on nebulizers. Some could not speak without gasping for breath. Others endured multiple bouts of cancer. No one connected their illnesses to the ash.

Leah Culwell, a school bus driver who for 30 years lived a mile from the pit, never questioned the company line on coal ash — until a capsized truck sent the material billowing over her bus. In the throes of a respiratory attack, her eyes swelled shut. She blew black mucus for days. Only then, Culwell says, did she suspect “this stuff is something more serious than they’re telling us.”

More than a decade would pass before residents knew the extent of pollution at the pit, where operators mixed coal ash with wastewater from oil and gas wells, another “beneficial use” permitted by the state. By 2009, the operation was taking in an estimated 1 million barrels of it annually, says Bert Fisher, an Oklahoma hydrogeologist who analyzed the site for the residents’ legal case. His analysis showed a plume of contamination — oilfield brine mixed with coal ash — tainting an on-site well, a neighbor’s well and two nearby creeks.

Fisher also sampled the dust in about a dozen Bokoshe homes abutting the pit and found coal ash particles in it. The ash samples contained elevated levels of the carcinogens hexavalent chromium and arsenic, much like those collected at the Making Money pit.

In 2009, inspectors for the state, which has primary oversight of the Making Money pit, witnessed coal ash “being blown into the air,” records show. They issued a notice of violation, alleging the operator had failed to fulfill multiple requirements, including taking “reasonable precautions” to keep dust from moving off site. Federal inspectors then detected “unauthorized” saline discharges in the two creeks near the pit, resulting in two administrative orders — one in 2009, the other the following year. The EPA accused the pit operator of leaking pollutants into “waters of the United States” and demanded it “immediately cease and desist,” which forced it to stop accepting oil and gas wastewater. The state issued its own order against the pit, banning the mixing of this wastewater with coal ash — but not the ash itself.

That same year, Bokoshe’s battle with coal ash became known at EPA headquarters. While chronicling cases of coal-ash contamination, employees of the agency’s solid-waste office contacted Susan Holmes, of the citizens’ group Bokoshe Environmental Cause, who offered testimonials and photographs detailing the ash dumping at the pit.

“Your letter, and certainly many of the photos, illustrate how a waste unit can be state-permitted as a landfill while it is actually a surface impoundment,” an EPA employee told Holmes in an email dated April 2009, likening the pit to an ash pond — the kind of wet and unlined disposal site later targeted by the agency regulation.

Heavy lobbying by industry

In the meantime, coal ash regulation had become an explosive subject in Washington. By October 2009, the EPA had forwarded a draft rule to the White House’s Office of Management and Budget for review. Under this draft, the agency essentially would have classified coal ash as “hazardous,” a distinction triggering a series of strict controls for its dumping. The EPA also proposed a crack-down on the use of recycled coal ash as structural fill for quarries, sand and gravel pits, and “large-scale” landscaping operations. It would have treated these fill applications as forms of disposal, not beneficial use, and regulated them like ash ponds or landfills.

Joe Wertz / StateImpact Oklahoma

A tractor-trailer enters the main entrance of the AES Shady Point coal-fired generation plant near Panama, Oklahoma.

The proposal set off a frenzy of lobbying by the utility industry, which has long opposed a “hazardous” label for coal ash. Records show utility companies, ash recyclers and trade organizations, such as the American Coal Ash Association and the Utility Solid Waste Activities Group launched an aggressive campaign throughout the OMB review. In 2009 and 2010, OMB analysts held more meetings on this environmental rule than any other in the office’s published history, 47 in all. Of those, 34 involved industry representatives. Environmental advocates and representatives of the public — including Bokoshe residents, like Holmes, who visited Washington twice to push for tighter coal ash controls — attended 13.

“It was such a blatant example of one-sidedness,” says Rena Steinzor, a law professor at the University of Maryland who has written extensively about the rulemaking.

Industry representatives reiterated longstanding claims about the costs of stringent environmental regulation — lost jobs, higher electricity bills. And they played down the hazards of coal ash. But as evidence of the ash’s threats mounted, the argument against federal regulation shifted. Records show utilities and ash recyclers asserting one dominant rationale for rejecting the EPA proposal: A hazardous designation would create a “stigma effect” on beneficial use, crippling the ash-recycling market. For ash recyclers, says the coal ash association’s Adams, the mere prospect of such a label could reap unintended consequences, such as dropped insurance coverage or building-code approvals.

In the end, the industry campaign had a clear effect: Post-OMB review, in June 2010, the EPA published a proposed rule featuring a weaker, less-costly alternative to its initial draft. It opted to designate coal ash “non-hazardous” and subject it to less-stringent federal requirements. OMB economists re-wrote the EPA’s cost-benefit analysis and added the hypothetical stigma effect, which they estimated would result in $233.5 billion in lost benefits. The costs, calculated over a 15-year period, dwarfed any anticipated benefits from regulation, says Maryland’s Steinzor, who has compared the EPA proposal to the OMB-edited version.

For several years afterward, the utility industry continued to flex its muscles in the regulatory process, inundating the EPA with comments, analyses, legal opinions and technical documents. The proposal remained stuck in the bureaucracy through all of 2011, 2012 and 2013. The EPA’s rulemaking “has been tied up in knots over beneficial use,” says Lisa Evans, of the environmental law firm Earthjustice, which, on behalf of 10 advocacy groups, sued the agency in 2012 over its stalled process and, two years later, won a court order forcing it to act.

By the time the EPA issued its final rule in 2014 — five years after its initial regulatory proposal — the agency had backed down. Instead of a rule treating coal ash as hazardous, the EPA issued minimum national standards that amounted to guidelines for states — guidelines that call for treating the disposal of coal ash as if it were household trash. The EPA retreated on another front as well: beneficial use.

The rule still puts limits on fill operations like sand and gravel pits. But it exempts other fill sites involving up to 12,400 tons of coal ash — enough to stack a football field six feet high — if they meet the criteria for beneficial use. To exceed this cap, operators must show the ash will not harm the environment.

The beneficial-use provision is ambiguous. It does not specify how a company should demonstrate the ash’s safety, for example. Even industry representatives acknowledge that it seems broad enough to allow for controversial applications, such as filling up silt and clay mines.

Still, they say, industry guidelines call for protective measures such as liners and water monitoring at these sites. “I see little real damage cases from large structural fills,” says James Roewer, of the Utility Solid Waste Activities Group, which is among a dozen industry groups that sued in July 2015, challenging various provisions of the EPA’s coal ash rule in court, including the tonnage limit for beneficial use. Since the EPA drafted its coal ash proposal in 2009, the solid-waste group has spent $1.2 million lobbying on either the agency rule or congressional measures that would have gutted it, disclosure reports show.

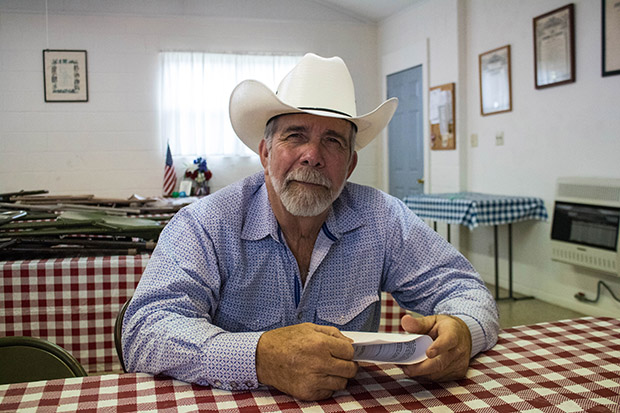

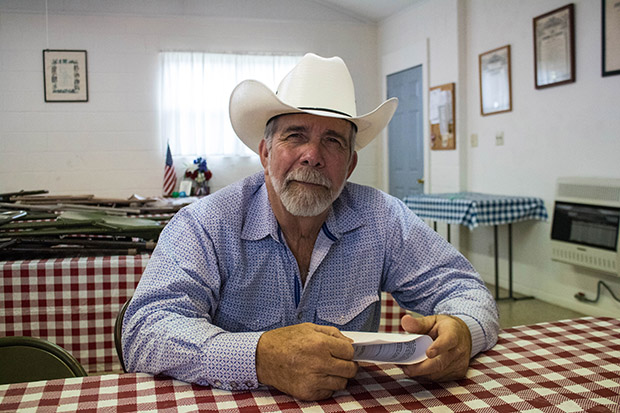

Joe Wertz / StateImpact Oklahoma

Herman "Dub" Tolbert, who lives near one of the coal ash pits, holds a health survey form from the Oklahoma State Department of Health, which is investigating cancer rates near Bokoshe.

The EPA declined interview requests from the Center, citing the pending litigation. In answer to written questions, the agency attributed its reversal on coal-ash recycling to “EPA agree[ing] with commenters that, if constructed correctly, large scale fill operations can meet all of the criteria for beneficial use.” The agency defends its coal ash rule as an effort to “distinguish between beneficial use and disposal.”

‘Nobody cares’

Back in Oklahoma, regulators do not seem as concerned with such distinctions. The state Department of Mines oversees the “coal-combustion byproducts” program authorizing the disposal of coal ash as reclamation fill for mine pits. The department’s director, Mary Ann Pritchard, did not respond to the Center’s interview requests; program officials declined to comment.

Privately, department employees defend minefilling as a beneficial use, which they say helps restore thousands of acres scarred by strip mining. Minefills look like mounds of coal ash temporarily but, they insist, end up covered with soil and grass. Oklahoma regulators have touted minefills now used as grazing lands. Some have written papers and given presentations extolling the state’s minefill regulations — at times, highlighting the Making Money pit in Bokoshe. Still, officials acknowledge the practice is driven by the utility industry’s need to get rid of its ash.

“It was an afterthought to use these pits for coal ash disposal,” one says.

State regulators say their oversight of the Making Money pit has been rigorous. Inspectors from the mining department — as well as the Oklahoma Department of Environmental Quality, which regulates air emissions — have visited the site, examined citizen complaints and monitored the company’s required reports, they say. Together the agencies have issued eight notices of violation against the pit, culminating in the 2009 enforcement actions over oil and gas wastewater and fugitive dust.

In 2010, regulators negotiated a consent order with the pit operator over the dust violation, requiring a plan to contain the ash, and monitoring its compliance. In 2012, they closed the case. Now, regulators say, the company has a more contained facility, replete with water sprayers and other equipment to wet the ash.

“We consider them in compliance,” says Sarah Penn, the environmental department’s deputy general counsel. While inspectors have since responded to complaints about the ash clouds — and issued a warning letter in 2014 over “visible fugitive dust” — Penn says the agency has yet to “see something we believe is a violation.”

Of the powdery ash, she says, “It looks worse than it is.”

To residents, the regulatory response has been feeble. Records show citizens logging complaints about the ash clouds for 11 years before environmental officials finally forced the pit operator to adopt a dust-suppression plan. Much of that plan reflects what the company promised years earlier — not just to neighbors but to state regulators, who, in 1999, issued their first violation notice over the dust. The state has dismissed most alleged violations and has never imposed a fine. Even the EPA’s orders, while stopping the use of oil and gas wastewater at the pit, have yet to yield any clean-up of ash-brine contamination in the creeks.

“People don’t want to do their jobs,” Tanksley says of the enforcement efforts. He remembers one state inspector assuring residents they would never see “with the naked eye” coal ash leaving the pit. Another attributed a billowy plume to a burning brush pile.

Environmental advocates have long argued that federal standards for minefilling could help plug state regulatory shortfalls. But the Interior Department’s mining office, which declared minefilling an “acceptable practice” in 1996, dismissed the need to do anything for years — until the 2006 National Academy of Sciences report. The report recommended that the mining office work with the EPA to develop “enforceable federal standards” that would create a regulatory floor for minefilling. In response in 2007, Interior officials published an advance notice of a proposed rulemaking, suggesting minimal changes. Nine years later, they have yet to unveil a draft plan.

Now that the EPA has issued its coal ash rule — and exempted minefilling — Interior is facing renewed pressure to develop its regulation. Evans, the Earthjustice attorney, explains that she filed the 2015 petition for a federal rulemaking on behalf of her group and 13 others after “plead[ing] with the office for years.” Under the federal mining law, Interior officials must respond to a formal rulemaking request or face possible legal action.

“We’re afraid minefilling will increase,” Evans says, echoing the fear among many advocates that utilities will turn to the unregulated practice as a way to get around the EPA’s coal ash rule.

Industry representatives counter that filling up coal mines with coal ash does not yield the same profit margin as other beneficial uses. Companies rely on minefilling more for the environmental benefits, they say, such as restoring old mines. Some states justify ash disposal in underground mines to combat another pollution problem: acid mine drainage. Coal ash, being alkaline, can help neutralize this acidic waste, the theory goes.

“I’d call that a benefit,” says Roewer, of the solid-waste group, which opposes tight controls on minefills. In recent years, he says, members of his lobby group and others have met with mining officials at Interior, urging them to allow the practice to continue as a beneficial use.

The mining office declined to comment, except to confirm that it intends to publish a proposed rule this year. In March, its director, Joseph Pizarchik, sent Evans a letter denying the Earthjustice petition as “moot” because the office “has already determined that a [minefill] rulemaking … is warranted.”

The jockeying for position in Washington seems worlds away to people in Bokoshe, including Tim and Sharon Tanksley and Susan Holmes. Their citizens group has relied on standard strategies to call attention to their plight — lobbying politicians, dogging regulators — as well as unorthodox ones. They have chased down ash trucks, scooped up ash samples, and staked out the pit at night. Once, they erected a billboard on the outskirts of town that announced: “WELCOME TO BOKOSHE, THE [COAL] ASH CAPITAL OF THE WORLD.”

In 2011, the Tanksleys, Holmes and three other residents sued AES, the pit operator and a dozen coal-ash haulers in Oklahoma district court, accusing the companies of “abnormally dangerous transport and disposal activities … pollution and contamination,” among other claims. Filed as a class action, the lawsuit sought remedy for those living within a three-mile radius of the Making Money pit — approximately 1,500 people — for “contamination of the environment in which they live, work and recreate and … the real and immediate threat of injuries.”

Joe Wertz / StateImpact Oklahoma

Bokoshe residents use creative methods to deal with airborne fly ash dust, such as this makeshift purifier made by taping an air filter to a box fan.

Viewed by Holmes as a “last-ditch effort” to shutter and clean up the pit, the lawsuit proceeded for a year before being removed to federal court, where it stalled and ultimately was dismissed. The residents’ attorneys argued the case belonged in state court, and filed multiple motions in federal court to move it back. Because of rulings there and in an appellate court that found the residents did not meet technical requirements enabling them to try the case in state court as a class, they are now left to pursue individual claims.

For many, the sense of powerlessness runs deep.

“Nobody cares,” Holmes says, alluding to state and federal regulators. “Everybody says, ‘It’s not up to us.’ It’s never anybody’s fault, and it’s always somebody else’s problem.”

Today, people in Bokoshe seem resigned to the dust in the air — and the destruction on the ground. Some have fled the town. Others have grown sick. In 2009, residents did an informal survey of the households located within a mile-and-a-half radius of the Making Money pit. Of 20 homes, 14 families had a relative who developed — and, in some instances, died of — cancer. A new survey is under way; organizers hope it will goad state health authorities to conduct an epidemiological study. An official with the Oklahoma State Department of Health says the state’s Central Cancer Registry plans to begin a preliminary study of cancer rates in Bokoshe this summer and should report its findings in the fall.

It all sounds familiar to Kristina Zierold, an epidemiologist at the University of Louisville who has researched the effects of coal ash on human health. In 2012, she explored the prevalence of disease in communities abutting ash dumps in that city. Residents had long complained that the billowing dust was making them sick, she says, “but there wasn’t any data.” In a year-long pilot study, she compared medical diagnoses and symptoms of 231 adults and children in what she calls “exposed” neighborhoods to 170 of their “non-exposed” counterparts, revealing a significant disparity. Of the two groups, the first had higher rates of illnesses, such as asthma, emphysema and cancer.

“We can definitely say that there’s this statistical difference,” says Zierold, who is now studying neurobehavioral symptoms among children exposed to the ash. Backed by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, part of the National Institutes of Health, this five-year study is the only federally funded research exploring a possible link between coal ash and poor health. The study is in its earliest stages, but based on her work so far, Zierold says this much is clear: “Coal ash does play a role in people’s health.”

In the past 11 years, Holmes has lost her sister and mother to cancer — lung and pancreatic, respectively — which she believes was tied to the coal ash. Her family lived along the pit’s haul route and breathed in the dust daily. Now living in her mother’s old house, Holmes says she promised her family she would stay until the dump closed. But her health is worsening. Her childhood asthma has returned, requiring an inhaler, a nebulizer, oxygen, and two medications. Recently, she was diagnosed with heart disease.

“We’re just a little Podunk town in the backwaters of nowhere,” Holmes says, explaining why so many residents believe the coal ash dumping has been allowed to continue. “We are considered throwaway people.”