Oklahoma State Parks Director Says State Parks ‘Not on the List’ of Core Services

-

Logan Layden

Logan Layden / StateImpactOklahoma

Shaun Pelkey and his daughter Ireland Pelkey enjoy the afternoon at one of Walnut Creek State Park's beaches on Keystone Lake.

State tourism officials are considering closing or transferring four more state parks. The agency, like many, has had its budget cut over the past four years, but the decision to defund state parks is about more than money.

The Oklahoma Department of Tourism and Recreation is considering cutting Little Blue, Snowdale, and Spring River parks, all near Grand Lake, and has already decided to give up control of Walnut Creek State Park near Prue in Osage Country.

The state leases the land Walnut Creek sits on from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and in October will break the lease a year early. The park will close unless the Corps can find someone else to operate it. The Kent Dunlap with the Corps’ Tulsa District says tribal, county and local governments, as well as commercial interests, are all being considered.

“We’ve had discussions with some different groups right now. And I’d be hesitant to — I don’t want to put them on the spot. But there is some interest,” Dunlap says.

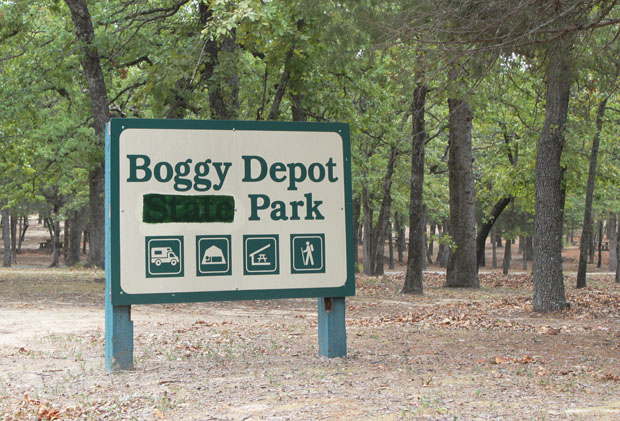

Joe Wertz / NPR StateImpact

Boggy Depot was among seven sites stripped of their state park status in 2011.

‘Part of Their Agenda’

The story was similar in 2011 when the state spun off seven state parks that were eventually all saved by local communities and tribal governments.

State officials cited budget cuts as the main reason for having to unburden itself of parks then and now, but standing on the grounds of Heavener Runestone Park, formerly Heavener Runestone State Park, Democratic Representative James Lockhart says budget cuts are just a convenient excuse to advance an agenda.

“I came into the legislature in 2010 and that was the year that Governor Fallin came in,” Lockhart says. “And Governor Fallin appointed Deby Snodgrass as the director of tourism, and two weeks into her job she starts closing state parks. So, I would just have to say that’s part of their agenda.”

Snodgrass declined StateImpact’s request for an interview, but State Parks Director Kris Marek says the government’s attitude toward state parks has changed since Gov. Fallin took office, and that attitude reflects the priorities of leaders at the state Capitol.

“What Deby Snodgrass brings to the table is a reality check,” Marek says. “There’s certain core services that are going to get the lion’s share of funds, and guess what, state parks isn’t on that list. Many people might be surprised, but those advocates are not the ones that are lobbying at the Capital. In reality it’s education, it’s corrections, it’s roads, it’s things that people see as core services. Am I happy that a core service is not state parks? No.”

Marek says many factors determine a park’s fate when budget cuts loom: size, attendance, profitability, historical significance, and ownership, among others. Money is only one part of the equation.

“Do we need more parkland in Oklahoma? Absolutely. We have a deficit. Less than 5 percent of the land in Oklahoma is public land,” Marek says. “Do we want to lose state parks? Not really. We would choose other options.”

Local Impact

Along the sandy shore of Lake Keystone at Walnut Creek State Park, Amy Coulter and her husband watch their granddaughter splash in the shallow water as they lament the state’s decision to end its lease of the wooded, 650-acre peninsula of campsites and horse trails Coulter says has the best beaches in the area.

“Honestly surprised about that because there is always a lot of people out here, and I was just kind of shocked that they were going to close it down,” Coulter says. “I think as worried as they are about tourism, maybe they should be worried about the local impact as well.”

Farther down the beach, Shawn Pelkey says locals have started a petition too keep the park open.

“I guess they needed, last I heard, was like 50,000 signatures,” Pelkey says.

Marek, the state parks director, says budgets are still getting tighter. It seems unlikely the loss of these parks will spur a greater appropriation from the state. So this might not be the last time another government or organization has to step up to save a former Oklahoma state park.