13th Grade: Older, Returning Students Strain Florida’s Community and State Colleges

Sagette Van Embden / Florida Center for Investigative Reporting

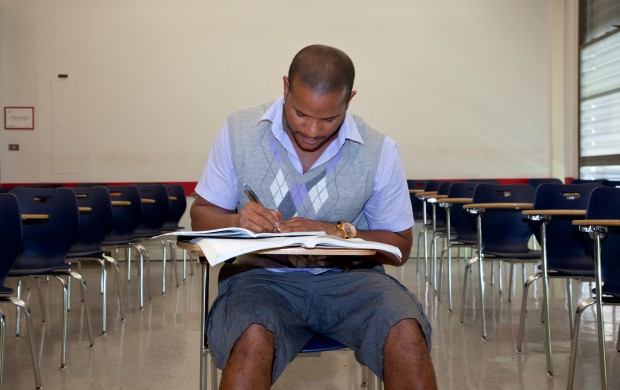

Chad Carroll, 36, needed to take remedial math classes when he enrolled in Miami Dade College. He isn’t alone. For Florida college students age 35 and older, 90 percent must take remedial math courses before they can begin college-level studies. “I didn’t accept it at first, but you have to embrace it,” Carroll said of remedial education.

Pepper Harth has always loved music. After high school, she studied voice and acting in New York. Her life took several turns. She married, had three children, divorced and sold real estate in New Jersey. She moved with her children to Seminole, Fla., in 2007. Work was not as plentiful in Florida as she had expected. She got by singing at nightclubs and weddings.

Last year, at 49, the single mom decided she wanted to do something more with her musical talents. Harth applied for federal financial aid and enrolled in the music degree program at St. Petersburg College in Seminole. Now 50, she aspires to use her future degree to practice music therapy in the health care industry.

Harth’s plans were set back, however, when she took the placement test that all Florida students must take before entering community college. She failed the math section. She wasn’t surprised: Math was never an easy subject for Harth in school, and that was more than 30 years ago.

Failing the math section didn’t mean she couldn’t go back to school. But it did mean that she had to take two remedial math courses before she could move on to college-level algebra. Actually, that turned into three semesters of remedial classes — she had to repeat one course.

Because the remedial courses don’t count for credit toward her music degree, Harth’s educational journey will take longer than she expected. It’s increasing her student loan debt — three-hour courses cost in-state residents between $300 and $350 at St. Petersburg College. And it’s costing Florida taxpayers who subsidize higher ed, as well as federal taxpayers who support her Pell Grant.

There are a lot of people in Florida going through what Pepper Harth is going through. Remedial classes in math, reading and writing are seeing a surge of students at Florida’s 28 community and state colleges — schools where all students are welcome as long as they have a high school diploma or G.E.D. From 2004 to 2011, Florida’s remedial education costs for both students and schools ballooned from $118 million to $168 million.

Part 1: Why one in two students taking a college placement exam wind up in remedial classes

Sidebar: Adding up the cost of remedial education

Part 2: What’s causing the rising need for remedial classes

Part 3: Why math is a persistent problem

Part 4: How the economy and financial aid are contributing to the need for remedial classes

Part 5: What educators are doing to help students in remedial courses finish their studies

Part 6: How new common education standards could make sure graduates are ready for college

These stories are the result of a reporting partnership between StateImpact Florida and the Florida Center for Investigative Reporting

The vast majority of students in these “developmental courses” are in some stage of going back to school after a break. An analysis by the Florida Center for Investigative Reporting and StateImpact Florida found that in the 2010-11 school year, 85 percent of students taking remedial classes were age 20 or older.

The trend with older students has been building for some time, but was accelerated by the Great Recession. Laid-off workers and those like Harth, who want to train for new lines of work or bolster their résumés, have been flooding onto college campuses. It isn’t just the weak job market that has been encouraging them to do this. The federal government is providing record amounts of financial aid.

When they get to campus, however, many find that their basic skills in math, reading and writing have deteriorated to the point that they are too rusty to take college-level courses. That’s especially true with math. According to the 2011 Florida College Readiness report, four of every five first-year, full-time students over 20 had to take remedial math courses. For those age 35 and older, the rate increased to 90 percent.

Hunter R. Boylan, director of the National Center for Developmental Education, says older students’ need for remedial math is natural. “You read every day, but when was the last time someone said, ‘Excuse me, Can you help me solve a polynomial equation?’ ” Boylan said. “It’s a skill that atrophies quickly and because it is not used regularly, it goes away.”

National Center for Developmental Education

Hunter Boylan, director of the National Center for Developmental Education, says older students frequently need to brush up on math.

Back to school

Historically, college enrollment by older students peaks during economic downturns. This recession is no different — except the spike is higher and more federal financial aid is available.

The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 created the biggest boost in federal student financial aid since the G.I. Bill. Federal funding for grants and student loans has continued to climb under President Obama, who has promoted easier access to education for the underprivileged and minorities. Funds available for the Federal Pell Grant Program, the largest form of federal aid that students do not have to repay, grew by more than $15 billion.

In Florida, students gladly took up the offer of more generous financial aid. As college enrollments shot up, so did the number of students requiring remedial classes. In 2007, the number of students who received federal financial aid and also required remedial work was about 48,000. By 2011, that number had more than doubled, to 97,000. Indirectly and inadvertently, the new federal dollars placed a greater demand for remediation courses on Florida’s community colleges.

Older students taking remedial courses said the availability of financial aid was a determining factor in deciding to go to college.

José Ramos is one of them. Ramos is a phlebotomist – that’s the person who takes blood samples for health tests. A Pell Grant enabled Ramos, 46, to pursue a nursing degree at St. Petersburg College. “Being the only provider in a household and for what I make, you can’t survive and go to school,” said Ramos, a father of four. “Normally, right now, I wouldn’t be in school. I’d be working two jobs supporting my family and not able to see my son grow up like I did my daughter.”

Ramos says he can earn more with a nursing degree and spend more time with his family.

Financial aid allowed Ramos to reduce his hours at work and concentrate on his studies. But his education has also taken longer than he anticipated due to his need for remedial math. Ramos didn’t score high enough in math on the entrance exam to take college-level algebra. Like Harth, he had to take remedial math courses and repeated one. He spent hours studying in the college’s learning lab in order to pass.

“I was disappointed and I hated to repeat math,” Ramos said of learning that he had to take the remedial courses. “But I guess it’s part of any job because no matter what you go into you are going to be using math. I just don’t think you will be using X’s and Y’s unless you are in something like engineering.”

Burning out

St. Petersburg College reading instructor Patricia Smith oversees the campus learning lab where Harth and Ramos have regularly studied and received tutoring. Smith considers them success stories – they’ve persevered through the remedial classes and continued on with their studies. That’s not the case with many older students who have to take developmental classes.

Statistics on the drop-out rate of older students who require remedial courses are not available. In 2007, Florida’s Office of Program Policy Analysis & Government Accountability reported that 48 percent of all remedial students don’t complete all of their college prep courses, let alone graduate. Anecdotally, instructors say the rate is higher among older students.

Older students have any number of reasons for dropping out. That can cloud the picture when it comes to determining whether all the taxpayer dollars and class time spent on remediation is worth it.

Some laid-off workers find new jobs and no longer have the time or inclination to stay in school. Older students also typically deal with outside stresses such as childcare and work. In recent years of recession and war, Smith said, she has taught homeless students, war veterans suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, and single parents fighting eviction from their homes.

As Smith sees it, even though many students don’t complete their programs, the ones who do make the added expense and instruction worthwhile. “A lot of them are diamonds in the rough and could go on to do better things,” she said. “We might be the last people our students ever see who encourage them to keep them going or turn them off from education. We have a huge amount of pressure on ourselves to turn out students who are learning more, and not just making passing grades, but to make it in the work force because if you can’t read properly how are you ever going to make it as a nurse?”

Even though older students often have greater needs for remediation, Smith and other instructors said they typically are more focused and determined to succeed than younger students. “They know it’s their last shot at something,” Smith said. ‘They will be more focused and they will help bring up the younger students in the class and actually act as nurturers and be great role models for younger students.”

Never Too Late

Harth said she’s more driven in her studies now than when she was younger. Returning to school later in life has been hard. “I tell everyone go to school while you are young because it is really difficult when you are a single mom and have had many, many years out of school and there is so much other stuff in your head.”

She’s utilized all of St. Petersburg College’s resources — the instructors, the advisors, the learning lab, the tutors and study groups – to help her get through her courses, particularly math. “The support here is unbelievable. But you have to work at it. You really have to be self-disciplined.”

Although it’s not required, she sees an academic advisor every semester to make sure she is on the right path with her courses.

Now that she’s completed her remedial math coursework, she’s tutoring students in other subjects and expects graduate in 2013. “I used to think I was too old to go back to school, but now I say never give up. It’s never too late.”