Grading Florida Schools: Opportunities Lag for Rural Students

Jessica Pupovac / StateImpact

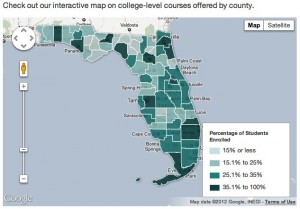

Click on the map to see which school districts have the most students taking advanced courses.

Florida high schools are being judged by the number of students enrolled in college-level classes. It’s tied to bonus money from the state.

But in Florida’s rural counties, small schools say they can’t compete with the opportunities at large urban schools.

Ashley Carr, a senior at Sneads High School in rural Jackson, Fla., is worried about how her course schedule will look to college admissions counselors.

“My senior year looks really ridiculous because I have 3 PE classes,” she said.

“But it’s not that I’m lazy, there’s just not anywhere else to put me.”

You can search for the opportunities at your school here.

Carr says she has already taken most of the classes her school offers.

That’s one reason the state started giving high schools more points for offering college-level classes, according to Jane Fletcher with the Florida Department of Education.

“To give schools incentives to make sure that all students have the option of participating in accelerated courses,” Fletcher said. “Because it’s been shown that it’s very important for college readiness.”

Fletcher says the formula is meant to protect students like Carr who go to schools with few class options.

But rural school leaders say they don’t have the resources to keep up. They say they are being wrongly branded with a low grade, and losing out on extra funding because of it.

The School Grading Formula is Tied to Extra Funding

About 20-percent of a high school’s grade comes from student performance and participation in college-level classes.

The state’s grading formula gives points to schools for participation in accelerated classes.

That can help schools reach a high grade, which may come with bonus money from the state.

Last year the bonus was $70 per student. Next year it will be $100 per student.

Sarah Gonzalez / StateImpact Florida

Rachel Belser is an Advanced Placement Chemistry teacher at Holmes County High school in Bonifay, Fla. near the Georgia border. It is one of 4 college-level courses offered at the school.

Schools are graded on a percentage of their students enrolled in college-level classes. But rural school leaders say they don’t have enough teachers to offer all the basic courses, and several different college-level courses on top of that.

Rachel Belser, an Advanced Placement Chemistry teacher at Holmes County High School, says large urban schools can offer more variety, so she says their participation numbers will always be higher.

“They have different opportunities than our kids do, but yet we’re graded the same and so it’s not a fair playing field at all,” she said.

For example, a C-grade school in an urban district, like Miami Springs Senior High in Miami-Dade County, offers more than 20 college-level classes.

Holmes County High, a C grade school in a rural district, offers 4 college-level classes.

Eddie Dixson, Holmes County High principal, says the state’s school grading formula was designed with large urban schools in mind.

“The state shot their model towards a high school with 2,000 kids in it. And my high school has 480. So I don’t fit that model,” Dixson said.

“It’s going to be hard for me to get an A when I don’t fit the model to begin with.”

The state says schools can make up the points if their students take college-classes online through Florida’s Virtual School program.

“That’s why the legislature has been really emphasizing the role of virtual schools,” Fletcher said, “to make sure that all students, no matter which schools they go to, have the opportunity to take accelerated courses.”

But in rural Florida, principals say there is just not a lot of interest.

In 5 years, Sneads High School has had two students enroll in an online college class.

Rural School Focus on Getting a Higher Grade

Rural schools say they’re focused on bringing in Advanced Placement (AP), International Baccalaureate (IB), and Dual Enrollment courses, where kids can earn actual college credit as well as high school credit.

“We’re scrambling now to figure out how to get more courses in here so kids can have access to them,” Dixson said. “It helps students that’s my first concern, but it also helps the school grade.”

Leaders say they are feeling the pressure to push students into college-level classes.

Sarah Gonzalez / StateImpact Florida

Students at Sneads High school discuss The Glass Menagerie during their college-level English class. Its called a Dual Enrollment class, where student take an actual college class in high school and earn both college and high school credit. Its one of two such college courses offered at the school.

But Laurence Pender, principal at Sneads High School near the Georgia border, says it may not be in the best interest of students.

It used to be that when one of his students wanted to take a college-level class, Pender would meet with that student.

“And based on my knowledge of that student I would sometimes recommend that they not take the class because of where they were maturity level, where they were academically.”

But then the state started giving high schools more points toward their school grade for offering college-level classes.

And Pender’s approach changed.

“They want to take the class, and I say, ‘Are you sure?’ And they say, ‘Yes sir,’ and I say, ‘Okay, go ahead.’ Because I know that that’s going to weigh on our school score.”

Pender’s high school just earned an A grade from the state for the 2011-2012.

“This year, everything worked out right,” Pender said.

But he admits his school grade was based on “a bunch of little things that I really don’t have anything to do with.”

In addition to participation and performance in accelerated courses, the state grades high schools on their graduation rates, the SAT scores of their students, and the score schools get on the state’s standardized exam—the FCAT.

Georgia Pevy, a junior at Sneads High, says small rural schools and their students should not be judged on their access to college-level classes.

She’ll be applying to colleges next year and she’s worried about competing with other students.

“They have different opportunities than our kids do, but yet we’re graded the same and so it’s not a fair playing field at all.”

– Rachel Belser, AP Chemistry teacher at Holmes County High School

“I feel like kids who are from bigger schools, who’ve take more AP classes and more Dual Enrollment are going to have a better chance of getting in,” Pevy said.

“I’ve taken honors, but we don’t have any AP classes yet, and I feel like I’m at a disadvantage because of that.”

But state data shows students who take college classes at rural schools are more likely to get college credit than students at urban schools.

Some say it may be because students are only taking one or two college classes at a time.

Last year the state gave more points for participation in accelerated classes, than it gave for performance in those classes.

Rural school leaders say its time to start focusing more on achievement and not simply counting who shows up.

“I would like to see the grading system take in our success more than our failures,” Belser said. “Instead of looking so much at where we’re lacking, let’s look at the positives too.”