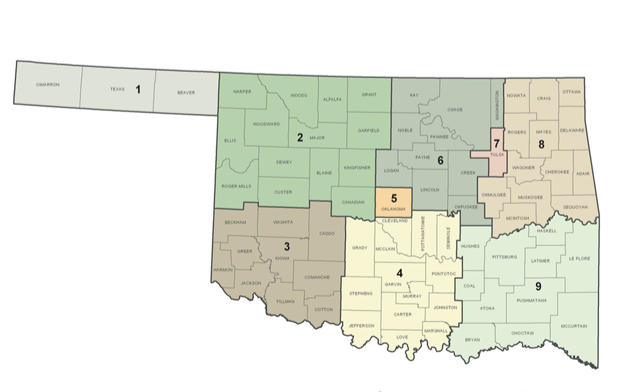

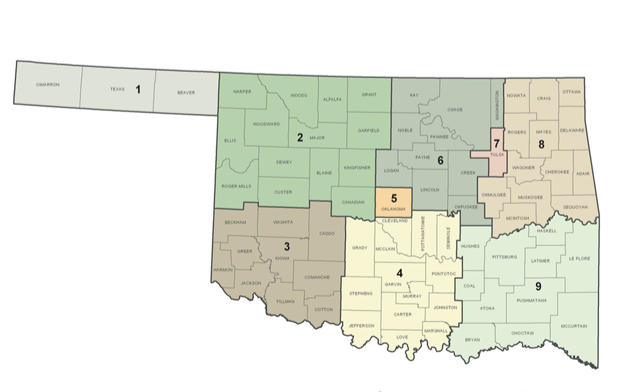

State Senator Eddie Fields' bill would create water planning districts that mirror the OWRB's membership districts.

State of Oklahoma

State Senator Eddie Fields' bill would create water planning districts that mirror the OWRB's membership districts.

State of Oklahoma

State of Oklahoma

State Senator Eddie Fields' bill would create water planning districts that mirror the OWRB's membership districts.

After 5 years of drought, Oklahoma’s dwindling water resources have the attention of state lawmakers. There are competing bills to study moving water from southeast Oklahoma to the Altus area, and to encourage self-sufficient, regionally based plans to meet future water needs.

Balancing the interests of Oklahomans who have plenty of water with those who desperately need it is a political fight, but not between Republicans and Democrats.

In southeast Oklahoma, it’s easy to find people who are passionate about water, like Chuck Hutchinson with Oklahomans for Responsible Water Policy.

“The town of Clayton lost their economic base [when Sardis Lake was built],” Hutchinson says. “Now they’ve converted over the years to a tourism base because of the lake. Now if they take the water out, they’re going to lose twice.”

And then there are the curious, like the women of the Wilburton 20th Century Club, where Hutchinson was speaking after being interviewed by StateImpact.

“Why can they not dam up some of their own land in western Oklahoma and provide their own water?” One woman asked. “Well, they don’t have any rain out there is one reason,” was the response from another club remember across the room.

Those in the know and those who want to know more seem to agree: regional panning — local water solutions using local water — is the best way to ensure there’s enough for everyone. That’s what the Oklahoma Water Resources Board’s Comprehensive Water Plan called for in 2012: breaking the state into eight regions that would set water-planning priorities. The agency’s Executive Director J.D. Strong:

Logan Layden / StateImpact Oklahoma

Oklahomans for Responsible Water Policy board member Chuck Hutchinson speaking to the Wilburton, Okla. 20th Century Club Feb. 10.

“This was the most popular recommendation that came from the public that engaged in the comprehensive water planning process,” Strong says. “They wanted to make sure that they had a voice in what happens going forward. So, once the plan is final and we get down to brass tax and start talking about priorities in developing water projects in the various regions of the state, they want to have a voice in that as well, not just have it dictated to them from Oklahoma City from the state capitol.”

Politicians generally like regional planning, too.

Four lawmakers, all Republicans, have regional planning-related bills, but just have different ideas about how regional planning should be done. Senator Eddie Fields, from Osage County in the northeast, has a bill that would do nearly everything the water board recommended. Senators Larry Boggs and Josh Brecheen, both from southeast Oklahoma, have bills to encourage the use of regional water over cross-state water transfers. Even supporters of moving water across the state see the merit in region-based planning, like Altus Senator Mike Shulz:

“If you’re not doing it, you should be doing it. Don’t wait for us to tell you to do it,” Schulz says.

The question is: Why hasn’t it happened yet? The water board’s J.D. Strong:

“The several attempts — including during the 2012 session there were at least eight bills filed to try to institute some sort of regional planning group process — all of them failed, I think out of an unfounded fear that this will set up water fiefdoms all over the state, and these will become quasi-regulatory bodies that will prevent water from being moved from where it is to where it’s needed,” Strong says.

This isn’t a partisan conflict, but a geographic one.

“Unfortunately, this has turned into an east versus west debate in our state,” Senator Brecheen says.

But that could be changing. Each of the state senators who authored regional water planning bills this session, including Eddie Fields, say their plans would not completely close the door on water transfers among different regions. They’re just worried too much water could be taken, ruining the livelihoods of their constituents. They point to Oklahoma City’s transfer of massive amounts of water from Canton Lake in 2013 and the damage it did to the tourism-based economy of the small town nearby, where boating and fishing are the community’s lifeblood.

“We’ve been doing water transfers for 75 years. That’s not going to change,” Fields says. “It’s more about getting everyone to work together. Water is a lot like politics. It’s local. And who know best about what the local needs are than those people in those particular areas of the state?”

It might not matter whether the legislature officially sanctions or encourages regional water planning at all. It’s already happening. The panhandle, southwest and northwest Oklahoma all already have grassroots regional plans in the works. Brent Kisling, who’s helping develop the Northwest Oklahoma Water Action Plan, actually opposes making regional planning law.

“I haven’t read his specific bill, but I do know that mandating water planning is probably not our best way to do it,” Kisling says. “You can encourage regional planning by tying funding for projects to projects that come through a regional planning effort.”

But developing those regional water plans is expensive. And without some kind of regional planning bill, there won’t be any state funding to help poorer parts of the state put their plans together.

You can track all the bills StateImpact Oklahoma is following by clicking here to visit StateImpact’s guide to the 2015 session.