NH Green Jobs Growth Picture Unclear

As the economy continues to limp along toward recovery, “green jobs” has become a buzz phrase, often tossed out as a panacea for our economic ails. But compared to the rest of the nation, New Hamphire’s share of this sector doesn’t exactly stand out.

In a study released earlier this month, researchers found that from 2003 to 2010, New Hampshire’s green jobs industry grew at an average of 3.5 percent a year, outpacing the rest of New England. But the result of that growth was lackluster. Only two percent of the state’s workforce holds down a green job, which places New Hampshire square in the middle of the national average.

Put another way: New Hampshire is less of a green economy leader than other states, and more like a student who just manages to raise their “D” grade to a “C” in the last weeks of the semester.

Defining Green Jobs

The definition of what exactly a “green job” is has been something of a moving target. But there is broad agreement that the green economy encompasses renewable energy and technology, environmentally-friendly products manufacturing, and other activities that, if they don’t directly benefit the environment, they don’t harm it.

There’s plenty of potential in the area for growth, as it only makes up two percent of jobs and more manufacturing jobs are going overseas. But which factors are most promising in stimulating growth in this industry? The record is unclear, and opinions are mixed.

Some Promise in New Segments

For the study, Brookings Institution researchers Mark Muro, Devashree Saha and Jonathan Rothwell broke the earth-friendly economy into 39 distinct segments. Among other things, they covered green building materials manufacturing, solar panel installation, organic farming, hydropower, mass transit, waste management and recycling…and the list goes on. And in this regard, at least, Rothwell says New Hampshire showed some promise.

“The fast growth is really in the new segments where companies tend to have been started in the late ‘90’s or 2000’s, and these are the areas that have a disproportionate impact on energy, whether it be energy efficiency or new energy, like biofuels and new battery technologies, solar photovoltaic all experienced great growth, both nationally and particularly in New Hampshire.”

Nobody seems to know exactly why there’s been fast growth in New Hampshire all of a sudden. That’s especially since the state hasn’t gone out of the way to craft a set of green business-friendly laws and subsidies.

Government Stimulus Cited as a Factor

State Office of Energy and Planning Director Joanne Morin says she has an idea of what’s been going on. “Stimulus is huge,” she said.

Although Morin’s office is a state agency, it’s almost entirely funded by the federal government. During normal budget years, OEP gets about $1.8 million in state funds, compared to $40 million from the federal government. Among other things, that money helps OEP to push energy efficiency in state and local government buildings and to maintain low-income weatherization programs.

But then the federal stimulus package passed, OEP got another $60 million dollars in federal money, and three years in which to spend it.

With extra help from federal officials, the Office of Energy and Planning has been focused on the green economy. Director Joanne Morin says more than a third of her office’s money — $23 million — has gone toward subsidizing weatherizing homes for low-income people. “We definitely have evidence of contractors who were construction contractors who were about to go out of business and went into weatherization and it sustained them through this recession.” Morin adds, “Our unemployment rate is below five percent…I believe the stimulus dollars had partial to do with that.”

A much smaller slice of OEP’s stimulus funding went toward what might be, in the end, a much more promising program for long-term green job growth. The Green Launching Pad is a green business incubator created at the University of New Hampshire. And it’s funded by $1.5 million in stimulus money passed down from the Office of Energy and Planning.

Eighteen months ago, University of New Hampshire Management Professor Ross Gittell helped co-found the Green Launching Pad, or GLP. Today, he also directs the program, which has launched nearly a dozen businesses over the past two years. Under the program, green startup companies throughout the state compete to become GLP companies. Once they’re accepted into the program, they get grants — up to $100,000 — and also mentorship from people at the University of New Hampshire and others involved in the project. The money can be used for marketing, manufacturing, web design, or whatever the company needs to move on to the next step in its development.

“What we have done so far is … provided not only jobs during this current period of weak performance in the general economy, but also laid the foundation. The businesses that we’re launching now will be able to provide jobs over a long period of time,” Gittell said. “At least a handful of them, probably half of those eleven, we expect, will be growing significantly over the next five to ten years.”

The poster-child for the Green Launching Pad is Sustain-X, a company specializing in compressed air storage. Besides just being able to store energy, though, Sustain-X has figured out how to generate energy from the compressed air itself, without adding any fuel. The company’s headed by Thomas Zarella, the former President of GT Solar, another New Hampshire clean energy company. Besides GLP funding, Sustain-X is rolling in tens of millions of dollars in capital support. The company’s also a media darling. Last year, it earned a spot on The Guardian’s “Global Clean Tech 100” list. Now, Sustain-X is upgrading to a bigger facility, moving from West Lebanon to Seabrook. Green Launching Pad Director Ross Gittell says the move will help Sustain-X create 25 more jobs.

So with all this success, did the Green Launching Pad money help launch Sustain-X?

Hard to say. Clearly, over the past few years, a number of investors have picked the company as a winning horse in the global renewable energy race. Whether it would have been seen as a winner without GLP funding remains a mystery.

But the Sustain-X story stands in stark contrast to that of Holase. For founder and CEO Evan Bonchemps, who has experience launching other companies outside the green sphere, GLP-funding made the difference between staying open—at least for awhile—and shuttering the company.

Unlike Sustain-X, Holase doesn’t offer a possible long-term solution to the current energy crisis. Bonchemps says he was inspired to create a portable battery and solar-powered traffic light system after witnessing the aftermath of a bad car accident on a highway.

The idea came to him in 2005, and within a few years, he had a working prototype. But Bonchemps’ had a hard time grabbing market share. “Raising enough operating capital has been very difficult in NH, so the Green Launching Pad money was a godsend for us, because it allows us to complete our manufacturing.”

Matt Stiles / NPR

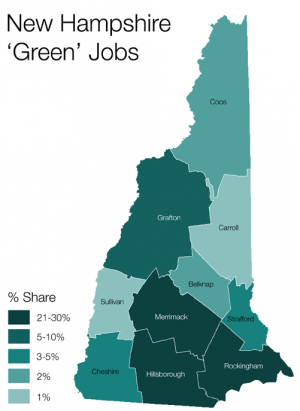

Southern counties have a larger percentage of the state's green jobs industry, according to a Brookings Institution study.

But even with the GLP money, it’s going to be a tough slog.

“The investment community itself in NH is just dried-up…I think since the economic downturn, it has gotten even worse in NH. Everyone is on the sideline just looking…Today, even as I’m talking with you, even though we have purchase orders from the State of NH, from bona fide customers, I was not able to get loans from any banks, even though we have valid purchase orders.”

So some companies have been able to get started, and remain open, with help from the Green Launching Pad, and the GLP was itself launched with federal stimulus dollars.

But is the stimulus really responsible for the uptick in NH green job growth? Gittell says he can’t be certain, because he hasn’t started tracking it. And since the stimulus doesn’t run out until next April, it’s tough to get a handle on final results. But, Gittell says, “Without stimulus money, we wouldn’t have been able to launch these eleven companies. I really can’t speak more broadly than that.”

Once stimulus funds run out at the end of April, Gittell hopes to have enough private funds in place to keep the program going.

Private Money to Grow Green Economy?

Using private money to accomplish something for the public good isn’t unusual in NH. In fact, it tends to be the preferred way to run things, as opposed to large-scale government intervention. Even so, this was a particularly brutal budget year for New Hampshire. The Legislature cut deeply into core health care services, and reduced the University System’s funding by 45 percent.

Republican Senate Majority Leader Jeb Bradley says given the cuts the state’s made to services, he’s not convinced Green Launching Pad would merit state funding.

“I mean, you talk of a hundred jobs created out of, probably roughly 720,000 jobs in New Hampshire right now. While the hundred jobs are important, in the overall scheme of things, it’s pretty small,” Bradley said.

The way Bradley sees it, the state’s already doing a good job of attracting all kinds of business—including green businesses. Rather than creating new policies, and dumping new money into subsidizing green tech, Bradley thinks the legislature needs to tweak the renewable portfolio standard law that’s already on the books, requiring utilities to purchase a certain amount of renewable energy, and in turn, creating a market for renewable resources.

“The advantages, right now in the law, go to anyone who creates new power. Well, what we’re seeing right now is that, in particular, the wood plants are barely hanging on, so they should be given the same incentives that new developers would get. And I think that would help them in the longer run be able to survive.”

Green Job Growth Gap

Within this emerging industry is a notable growth disparity. Eight out of 10 of New Hampshire’s green jobs are in Rockingham, Merrimack and Hillsborough counties. That southeastern part of the state dominates both clean tech and the overall green economy. Granted, that’s where most of the state’s population lives. But still, the gap is extreme.

According to the Brookings report, while Merrimack County saw 13 percent growth in green jobs between 2003 and 2010 during the same period, Coos County only saw 2 percent growth. And with the North Country’s expansive forests and strong history with paper mills and other wood products work, using government policy to encourage existing biofuel plants might be a good, low-cost way to jump-start that lagging economy.

It’s a philosophical question: Where can the government put its money to get the highest economic return—and the most jobs?

Bradley lays his feelings—and those of his party—down clearly, “Government doesn’t need to get overly involved in picking winners and losers.”

But Evan Bonchemps, who heads the struggling startup Holase, says that’s exactly what the government’s doing, anyway, by offering tax breaks to established companies who face higher tax burdens. “As an early-stage company, we cannot take advantage of these things, because we have no revenue, we have no products, and we have no income, so these tax breaks that they’re talking about that will help grow businesses, for us, it’s an invalid statement,” Bonchemps said. “I think they could use the funds they claim they’re providing and…create a fund for early-stage companies. That would help.”

The questions swirling around New Hampshire’s fledgling green economy point to a much larger, national problem, says Brookings Institution Senior Researcher Jonathan Rothwell.

“There are 2.7 million [green] jobs nationally, but a much smaller number in these new, dynamic clean tech segments. And partly, that’s because we’re not getting the project financing, the late-stage financing right. And China has really overtaken us in this stage in recent years. And they have plants that employ thousands of workers in making these sorts of technologies. And that’s partly because the labor costs are so much cheaper, but that’s also partly because they’ve managed to solve these financial problems.”