The Nittany 1 Solar Farm, seen here from outside protective fencing in Lurgan Township, Franklin County on Nov. 24, 2020.

Rachel McDevitt / StateImpact Pennsylvania

The Nittany 1 Solar Farm, seen here from outside protective fencing in Lurgan Township, Franklin County on Nov. 24, 2020.

Rachel McDevitt / StateImpact Pennsylvania

Rachel McDevitt / StateImpact Pennsylvania

The Nittany 1 Solar Farm, seen here from outside protective fencing in Lurgan Township, Franklin County on Nov. 24, 2020.

About a year ago, Dan Brockett’s phone started ringing with calls from people asking for advice on solar developers who wanted to lease their land.

At first, the Penn State Extension educator thought it might be a scam. He wondered if Pennsylvania even gets enough sun to make solar energy worth it.

Brockett soon discovered energy companies are willing to bet that it is. There are more than 350 solar projects proposed for the commonwealth pending before the region’s electric grid operator, PJM.

Now, Brockett is fielding different calls.

“In some communities, these projects seem to go through without a cricket chirp,” Brockett said.

But in other places, municipal leaders and neighbors are alarmed at the prospect of living next to hundreds of acres of solar panels and want to know if they can do anything to stop it.

Some communities have already begun to fight. In Mount Joy Township, Adams County, a group of 60 people hired a lawyer to contest a conditional use permit for a 75-megawatt solar field. Hearings have been ongoing for months, and are scheduled through January 2021.

With Pennsylvania on the cusp of a solar development boom, this fight could repeat in other municipalities who find themselves unprepared.

Listen:

The Brookview Solar project that Florida-based NextEra Energy Resources plans to build along Baltimore Pike, southeast of Gettysburg, has been in the works for a few years. The company is leasing 1,000 acres and plans to build on about half the area. Some of the 18 landowners leasing to the project signed contracts in 2017.

But it came as a shock to some who didn’t sign leases.

Todd McCauslin said the “nightmare hit” when he and his family came back from a vacation in Florida last December to find a note on their garage door.

“That’s how we found out initially that this was even going on. We had no clue,” he said.

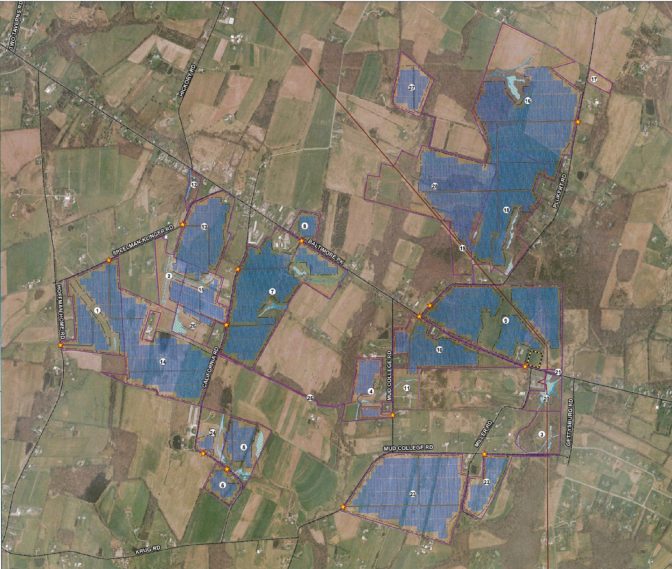

The proposed Brookview solar plant would sit on farmland near Route 97, which leads to Gettysburg. This plan submitted to Mount Joy Township, Adams County shows the project spanning 1,000 acres across 26 parcels of land. Panels are represented by the shaded areas.

McCauslin said he’s since spent at least 1,000 hours researching and organizing against the project.

One of his biggest complaints is a lack of transparency around the project, from NextEra and the township, which updated zoning laws in 2016 to accommodate solar.

NextEra spokeswoman Lisa Paul said the company has gone to “great lengths to share information,” including creation of a public website and Facebook page about this project, a mailer sent to residents and multiple advertisements about the project in the Gettysburg Times.

Messages left at the township office and emails to township supervisors were not returned.

McCauslin and other opponents say they’re concerned about the solar plant’s impact on property values and local wildlife. They fear it will cause problems with stormwater runoff. One person whose home would be surrounded by the project said it would be like living “in a prison;” another compared it to a concentration camp.

“I personally feel that it’s a desecration of what happened here.” — Tom Newhart, Mount Joy Township business owner

Paul said NextEra will continue to address any questions through the conditional use hearings.

“Once the Conditional Use process is complete, we can focus on the design and work with the Township and residents to design a project that addresses any questions,” Paul said in an email.

Some of the arguments flying around against this project — and others across the United States — echo disinformation put out by self-titled experts and think tanks that appear to be neutral but are tied to fossil fuel interests and climate science deniers.

But while these claims can contain a grain of truth, they are often exaggerated or don’t include needed context. For example, while solar cells could be considered “toxic” because they contain the heavy metal cadmium, scientists at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory say there’s no evidence panels contaminate the environment while in use.

Many opponents say they aren’t “against solar” but don’t think Mount Joy is the right place for it.

Rachel McDevitt / StateImpact Pennsylvania

One of the many signs protesting a proposed solar project in Mount Joy Township, Adams County is seen here in front of the Iron Horse Inn on Nov. 24, 2020. Owner Tom Newhart said the project could hurt the tourism industry in the area, just outside Gettysburg.

Tom Newhart, who owns a farm and a bed and breakfast that would border the proposed project, is concerned about the impact on his business and tourism.

But more important to him is that solar panels could go up on historic Civil War farmland. He said soldiers wounded in the battle of Gettysburg were cared for in homes in Mount Joy.

“I personally feel that it’s a desecration of what happened here,” he said.

The ferocity of this opposition took Clayton Wood by surprise. His family was among the first to lease land to the project — in their case, more than 150 acres.

Wood is the fourth generation to own his family’s farm in Adams County. Though he now lives in New York, where he manages a dairy, he thinks of Mount Joy as home. His parents still live on the land and he wants to be able to pass it on to the fifth generation.

“I can’t imagine what they could think of that would be negative.” — Glenn Dice, Franklin County landowner

Over the years, the family has been approached by other developers. One even wanted to put in a waterpark.

Wood said it’s important to his family that the land provide a “purposeful and relevant” use.

For a long time, that was agriculture, but now the economics of a small dairy farm don’t make sense for the Woods. Solar does. Wood’s lease doesn’t allow him to disclose how much he’s making, but Dan Brockett, with Penn State Extension, said the range in Pennsylvania is between $300 and $2,000 an acre per year.

Wood said, on top of that financial stability, it feels good to be a small part of addressing climate change.

“I still feel like we’re harvesting something, and being stewards of our land resources, which is essentially what farming is,” he said.

The fight in Mount Joy stands in contrast to how industry watchers say most projects have been developed in Pennsylvania so far. Early projects were small, and they went up without a fuss.

Even a 70-megawatt project for Philadelphia planned in Straban Township, northeast of Gettysburg, won’t need a public hearing. The developer is working with the township on permit conditions.

In neighboring Franklin County, Lightsource BP built a 70-megawatt plant spread across three townships. It is already supplying power to Penn State.

One of the project’s landowners, Glenn Dice, said it took nine years from initial lease to construction. Lurgan Township officials said that’s because the developer was waiting for a buyer, not because there was opposition.

“I can’t imagine what they could think of that would be negative,” Dice said. “Because it’s planet Earth, we want to preserve it for future generations. And I think this is definitely in that direction.”

Solar is a legal use in Pennsylvania, so municipalities have to allow it, but they can restrict things like size and where it can be built. There are more than 2,500 municipalities in the commonwealth, and solar requirements could look different in each one.

Mohamed Rali Badissy, a law professor at Penn State Dickinson Law who spent years working on energy matters at the U.S. Department of Commerce, said there’s no set guidance for how communities should zone solar.

“Internationally, domestically — there are no standards in this segment yet,” he said.

Badissy and a team are reviewing 2,000 zoning laws from Pennsylvania municipalities to see how they’re handling solar. They’re about halfway through, and so far, only about 9 percent mention solar. About 5 percent have regulations for utility-scale projects.

Badissy says that means solar development is still a largely undefined activity in the state.

Of the 368 solar plants in service and planned for Pennsylvania in the regional electric grid’s New Services Queue, more than 200 were added this year. About half of those have been added since September.

More than 200 of the projects in line would supply 20 megawatts of power or more. It can take between 5 and 10 acres worth of solar panels to produce 1 mw of power, according to the Solar Energy Industries Association. SEIA says 1 mw can power about 190 homes.

Only a fraction of those projects might reach the finish line.

Colin Smith, a solar analyst with energy research firm Wood Mackenzie, said it makes sense for multi-million-dollar solar companies, like NextEra, to place a few early bets in a state like Pennsylvania.

He said the recent uptick in proposed projects is driven by two things: The price of solar panels has fallen and developers are getting strong signals from big companies and governments that the world is moving to clean energy.

He said more than 20 percent of projects in development across the country have some sort of corporate buyer. That’s grown from about 10 percent in 2016.

Developers will lean toward areas with clear regulations to avoid potential lawsuits and save money, said Badissy, the law professor. So, for townships with a lot of open space, there is some urgency to figure out how to write a regulation that protects the community while lowering development costs.

“So at the end of the day, cheap power is produced, which is what everybody really wants from this,” he said.

Solar’s growth reminds Badissy of Pennsylvania’s shale gas boom. It started with land agents securing leases with private landowners, and then suddenly a big new thing was happening in people’s backyards.

If the state government decides it’s too important economically or for decarbonization goals to leave up to municipalities, a greater local-versus-state debate could emerge.

“A lot of us are watching this wondering which direction it’s going to go. We just don’t know,” Badissy said.

For now, solar’s direction is being decided mainly by rural townships, many of which haven’t traditionally hosted energy projects.

Each one will soon have to choose whether, and how, solar fits with its vision of the future.

StateImpact Pennsylvania is a collaboration among WITF, WHYY, and the Allegheny Front. Reporters Reid Frazier, Rachel McDevitt and Susan Phillips cover the commonwealth’s energy economy. Read their reports on this site, and hear them on public radio stations across Pennsylvania.

(listed by story count)

StateImpact Pennsylvania is a collaboration among WITF, WHYY, and the Allegheny Front. Reporters Reid Frazier, Rachel McDevitt and Susan Phillips cover the commonwealth’s energy economy. Read their reports on this site, and hear them on public radio stations across Pennsylvania.

Climate Solutions, a collaboration of news organizations, educational institutions and a theater company, uses engagement, education and storytelling to help central Pennsylvanians toward climate change literacy, resilience and adaptation. Our work will amplify how people are finding solutions to the challenges presented by a warming world.