A man water-skis behind a boat on the Susquehanna River, as seen from City Island. In the foreground is the Pride of the Susquehanna boat. The state Capitol is visible across the river.

Brett Sholtis / WITF News

A man water-skis behind a boat on the Susquehanna River, as seen from City Island. In the foreground is the Pride of the Susquehanna boat. The state Capitol is visible across the river.

Brett Sholtis / WITF News

Brett Sholtis / WITF News

A man water-skis behind a boat on the Susquehanna River, as seen from City Island. In the foreground is the Pride of the Susquehanna boat. The state Capitol is visible across the river.

(Harrisburg) — An environmental advocacy group says unsafe levels of the bacteria E. coli in the Susquehanna River are putting residents at risk — and it says Harrisburg’s antiquated stormwater and sewer system is to blame.

Working with the Lower Susquehanna Riverkeeper, Environmental Integrity Project sampled water from City Island beach and at locations near the state office complex and the governor’s residence from June 15 to July 31.

It found E. coli bacteria levels along the waterfront “averaging almost three times higher than would be safe for swimming or water-contact recreation,” according to a report released today. Seven of those samples showed E. Coli levels 10 times higher than what is acceptable.

The bacteria is transmitted through food and excrement and can cause stomach cramps, bloody diarrhea and vomiting, according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It is potentially fatal.

“We found that Pennsylvania is failing to enforce the federal Clean Water Act, and allowing a major sewage contamination right in its own backyard in Harrisburg,” said Tom Pelton, spokesman at Environmental Integrity Project. Pelton said the raw sewage is also contributing to algal blooms and oxygen dead-zones that harm fish and aquatic life.

The source of the pollution is Harrisburg’s nearly century-old water system, which “combines sewage and stormwater and intentionally pipes raw human feces and urine directly into local rivers and streams” during heavy rainfall, Pelton said.

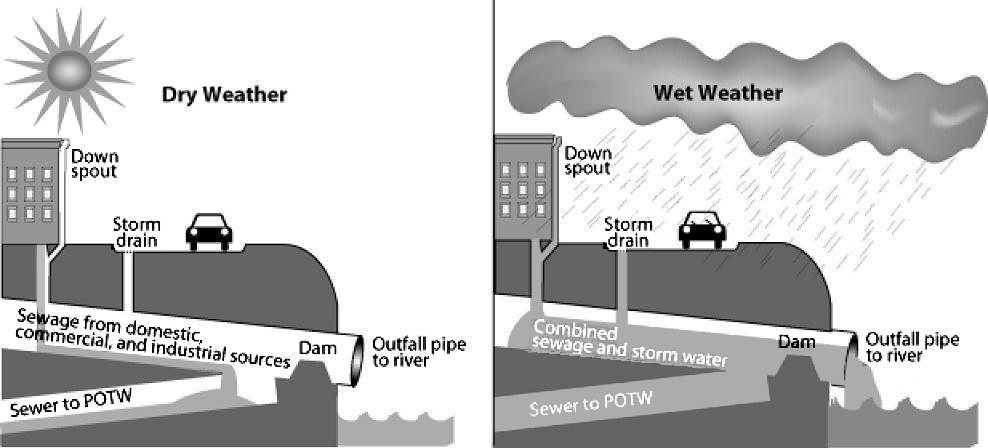

This Environmental Protection Agency illustration, used by Environmental Integrity Project in its report, shows how combined stormwater systems work. In Harrisburg, outfall pipes are below the surface of the river.

That happened on 150 days in 2018, according to Tanya Dierolf, sustainability and strategic projects manager at the city’s water authority, Capital Region Water. During that time, 1.4 billion gallons of combined stormwater and sewage flowed into the river.

This issue is not new to Harrisburg. In 2015, the Environmental Protection Agency and state Department of Environmental Protection sued the city for failing to address its combined sewer overflow problem. Capital Region Water entered into a consent decree with the regulatory agencies and developed a plan to address the issue.

In recent years, increased rainfall has been making the problem worse, Dierolf said. 2018 was the second-wettest year on record in Harrisburg.

Across the city, there are 59 “sewer sheds,” each of which can trigger the sewer overflow to the river if too much stormwater is flowing into the wastewater, Dierolf said.

It used to be more common for one or two of those sewer sheds to dump some overflow into the Susquehanna. However, that’s changing.

“…Bigger, more widespread and longer duration storms have a wider-reaching effect, and the intense soaking we received in 2018 elevated groundwater tables further aggravating the situation, as there was nowhere for water to go,” Dierolf said.

Rainfall isn’t expected to decrease, either. Climate models predict the region will experience more precipitation as temperatures continue to rise. The state’s Climate Action Plan says annual precipitation in Pennsylvania has increased by about 10 percent since the early 20th century, and is expected to increase by another 8 percent by 2050.

Brett Sholtis / WITF News

A Capital Region Water sign posted along the east bank of the Susquehanna River reads “Warning. Combined sewer overflow. Avoid contact with discharge.”

As part of Capital Region Water’s consent decree with the government, it has developed a plan to add green infrastructure and stop some of the sewer overflow. That plan is projected to cost $315 million over the next 20 years.

As expensive as that sounds, proposals to overhaul the combined stormwater overflow by doing things like adding pipes and wastewater tanks were much more expensive, Dierolf said.

“As it is we struggle with affordability issues, and we are talking about the need to spend even more,” Dierolf said, noting that the water authority is considering adding a stormwater impact fee to city residents and property owners to help pay for upgrades.

Meanwhile, the city is considering selling Capital Region Water to a private water company, a move that it has said could help to fund infrastructural improvements. A spokesman for Mayor Eric Papenfuse said he was unavailable for comment Wednesday evening.

At Environmental Integrity Project, Pelton called on the state to help shoulder the costs.

“I talked to a family playing at City Island, and the father said to me, you know, it’s unfair that this beach is closed. I used to swim right here. Why can’t my kid swim at this beach anymore? And the reason is, Pennsylvania is neglecting its responsibility to solve this sewage overflow problem.”

A spokesman for Gov. Tom Wolf said the office will review the report, which had not been made available to them as of Wednesday evening.

Wolf’s office said the governor’s Restore Pennsylvania proposal includes a provision to establish a stormwater control grant program.

That initiative would be funded by a severance tax on natural gas drilling, an idea that has been rejected by the Republican-controlled legislature.

StateImpact Pennsylvania is a collaboration among WITF, WHYY, and the Allegheny Front. Reporters Reid Frazier, Rachel McDevitt and Susan Phillips cover the commonwealth’s energy economy. Read their reports on this site, and hear them on public radio stations across Pennsylvania.

(listed by story count)

StateImpact Pennsylvania is a collaboration among WITF, WHYY, and the Allegheny Front. Reporters Reid Frazier, Rachel McDevitt and Susan Phillips cover the commonwealth’s energy economy. Read their reports on this site, and hear them on public radio stations across Pennsylvania.

Climate Solutions, a collaboration of news organizations, educational institutions and a theater company, uses engagement, education and storytelling to help central Pennsylvanians toward climate change literacy, resilience and adaptation. Our work will amplify how people are finding solutions to the challenges presented by a warming world.