Data trove offers new details on complaints to DEP during shale boom

-

Susan Phillips -

Jon Hurdle

Susan Phillips/ StateImpact Pennsylvania

Kim McEvoy is one of more than 4,000 residents who contacted DEP after noticing changes to water quality she believed may have been connected to nearby gas drilling. DEP concluded drilling did not impact her water. She has since moved away to live in an area connected to a municipal water supply.

Pennsylvania’s Department of Environmental Protection received 9,442 public complaints about environmental problems in areas where unconventional natural gas development occurred from 2004 to the end of November 2016, an investigation reported, unveiling a trove of documents from the state’s natural gas boom.

The three-year investigation conducted by the Pittsburgh-based Public Herald watch-dog website, said 4,108 of the complaints were prompted by water-quality problems while others were driven by concerns including air-quality, spills of drilling materials, property damage, and leaking gas.

The data cache was obtained by Public Herald from requests filed under the state’s Right to Know law. It may fuel the longstanding public debate over whether fracking and other gas-development activities hurt water and air quality. At the very least it provides a wealth of new data for researchers.

Complaints to DEP are summarized in a spreadsheet under headings such as “muddy stream,” “gas well rupture” and “bad odor in house.” Each complaint is identified by county and municipality, and records the dates when it was received, responded to, and “resolved.” Complainants’ names and addresses are redacted. A map created by Public Herald with help from another nonprofit organization, the environmental group FracTracker, includes the geographical data points, which allow the user to view DEP’s investigation reports and water tests for each complaint.

Of the water-quality complaints, only 284 were found by the DEP to have been related to oil and gas development, a number that has not changed over the last year, according to DEP spokesman Neil Shader. That number increased from 248 reported by DEP for the first time in 2014. The confirmed cases represent just about seven percent of the total complaints investigated by DEP.

The data show that complaints rose as gas activity across the state increased. The complaints include both unconventional wells, where producers drill deep into tight shale formations and use hydraulic fracturing to release gas, as well as conventional wells that tap more shallow oil and gas formations. It’s not clear how many of the complaints are related to wells tapping the Marcellus Shale formation.

The DEP’s Shader confirmed the numbers of overall complaints and water-quality cases released by Public Herald, and argued that the department responds to all complaints. “As the data provided to Public Herald shows (but is not prominently reported), the majority of complaints are responded to and resolved quickly,” Shader wrote in an email.

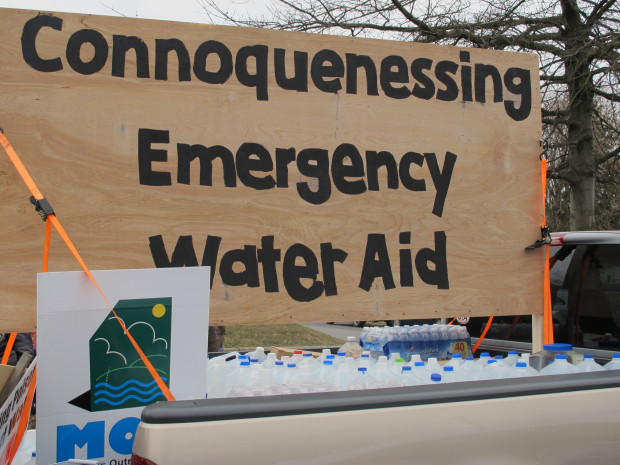

Susan Phillips / StateImpact Pennsylvania

Residents of Connoquenessing Township, Butler County began complaining of water issues in 2011. DEP investigated but did not find that gas drilling was to blame. Residents are still relying on donated drinking water.

Public Herald co-founder Joshua Pribanic said the now publicly accessible database, along with the detailed water investigation reports, took three years to compile. Pribanic says he and others drove all over the state to DEP’s regional office to do file reviews.

“All of this was to answer one question,” Pribanic told StateImpact, “How many cases of water contamination from fracking have been reported, and what happened?'”

Fracking, which for oil and gas producers refers to a specific part of the production process, did not necessarily occur in every case, either because it was a shallow gas well that did not utilize the technology, or because residents noticed changes to their water before hydraulic fracturing occurred.

Researchers and water quality experts say a number of factors contribute to the disparity between the total number of complaints and cases of confirmed water contamination by DEP.

Pennsylvania’s unregulated water wells

Pennsylvania is one of only two states where private well water is not regulated. So water issues are common, regardless of nearby gas drilling. There are no statewide construction standards for the residential water wells, which provide drinking water to about 3.5 million people in rural areas.

“This opens up the door for [water quality] issues because that means you don’t need to have a good seal on the well,” said David Yoxtheimer, a hydrogeologist with Penn State’s Marcellus Center for Outreach and Research. “Other states have standards and inspectors. In Pennsylvania there’s not even that mechanism. As with any industry there are people who do a great job, and others who don’t.”

The DEP has no jurisdiction over private wells, and unless a pollution incident creates a complaint, the agency will not test the water. Once an investigator concludes drilling activity did not impact the water well, the agency considers the case closed and it’s up to the well owner to take further action.

Connecting the dots is not very easy

Rob Jackson is a Stanford University earth sciences professor who researches the impact of oil and gas production on water supplies. Jackson has conducted research in Pennsylvania that resulted in published peer-reviewed articles.

He says in many cases, the well water is already contaminated before gas production, and other things like road salt, agricultural run-off and leaking septic systems can pollute well water.

But Jackson also says even in the cases where gas drilling may be the culprit, it’s difficult to prove.

Susan Phillips / StateImpact Pennsylvania

Residents in the village of Rae, in Washington County, said back in 2012 that they complained to DEP of bad odors and water contamination they thought were related to gas drilling. Edna Moten says they’ve been frustrated by the agency’s response, which did not conclude gas drilling was to blame. She did not have a baseline water test.

“One thing to keep in mind is that the bar is really high,” said Jackson. “If there’s any doubt about the cause of poor water quality, the DEP is not going to rule against the industry because the burden of proof falls on the homeowner to show cause and effect from drilling activity.”

Jackson says unless there is a history of water tests showing before and after changes to water quality, it’s almost impossible to make the link.

“That’s why you see most of these people unsatisfied by the outcome of these reviews but unable to show the drilling caused their problem…I‘m certain a higher portion of those people had water impacted by drilling but perhaps couldn’t prove it,” he said.

The state updated its oil and gas law in 2012, which made gas drillers responsible for any impacts on water wells that lie within 2500 feet of unconventional wells, and 1000 feet of conventional wells, unless proven otherwise. The law has in effect, prompted the drillers to now do baseline water testing.

Mapping out complaints

The Public Herald report presents a statewide map, color-coded according to the volume of complaints; summarizes the number and type of complaints by county and then breaks them down first by municipality, and then by individual complaint.

For example, in Delmar Township, Tioga County, there were 27 water-quality complaints during the report period, according to the data. One unidentified complainant, living near a gas well site operated by East Resources, told DEP in September 2010 that water in his well had “become turbid and has a bad taste,” according to the DEP document. “Complainant believes water has been impacted by nearby drilling activity,” it said.

Susan Phillips / StateImpact PA

Victoria Switzer in her home in Dimock,Susquehanna County 2012. Switzer and her neighbors complained to DEP, which did find Cabot Oil and Gas responsible for methane migration, but not other contaminants listed on water tests. Residents, who did not have baseline water tests, sued Cabot. Most, including Switzer, settled their cases.

DEP inspectors sampled the water and found chloride, barium and total dissolved solids were above state drinking water health levels, and that sodium, strontium and methane were “elevated,” the document says.

Over four pages, the inspectors describe the sampling and treatment of the well over a 12-month period during which levels of barium, chloride and TDS in a monitoring well fell below health limits but iron and manganese remained above those limits.

In a letter to the resident in January 2012, the DEP says it found the chemicals and methane at elevated levels but concludes that gas drilling was not to blame.

“The presence of dissolved methane in your water supply appears to be related to background conditions,” the letter says. “At this time, the Department’s investigation does not indicate that gas well drilling has impacted your water supply.”

On methane, the letter says inspectors found the gas at 11.4 mg/L in the complainant’s water, above the 7 mg/L at which the department notifies residents of the potential hazards of methane but below a 28 mg/L “level of concern” that risks an explosion. The letter says several compounds were found at “above Department standards” but it does not say whether those chemicals were treated or represented a threat to the resident’s health.

In Greene County, a resident in Aleppo Township complained to DEP in July 2009 that his or her water supply had been “lost” after Penneco Oil drilled a well nearby about a year earlier. The resident had been “hauling water” since the well was drilled, the report said.

DEP inspectors investigated, and concluded that the gas well “does not appear to be in a spot where drilling would influence water flow into the water well.”

“There is not enough evidence to hold the operator responsible for diminution of the aquifer and well water in question,” the inspectors said in August 2009, according to the DEP document.

But after another complaint, from Carmichaels Borough, also in Greene County, the DEP directed an unnamed operator to “fix sediment traps” after the resident complained in April 2011 that contaminated water from an operator’s unlined drill pond was leaking on to his or her property.

A treasure trove for researchers

Dr. Richard Horwitz, an environmental science professor the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, said the DEP data appears to be the first such collection to be publicly released, and its quantity and nature could offer researchers new insight into the relationship between fracking and drinking water.

“This gives me a sense that it’s worth doing more work to find out what’s going on,” Horwitz said in an interview.

Susan Phillips / StateImpact PA

Dimock resident Scott Ely at a protest in 2012. Ely worked for Cabot Oil and Gas and later became a whistle blower when he says the company ruined his well water. Ely sued Cabot and a federal jury awarded him and his family $2.7 million.

But he warned that some public complaints could have been prompted by the continuing publicity over water contamination, leading people to assume without evidence that their water had been impaired by nearby gas industry activity.

Dr. David Velinsky, head of the Academy’s Department of Biodiversity, Earth and Environmental Science, said the cache of DEP data may warrant an independent analysis.

“There is something there,” he said. “We would want to take a deeper dive into it. The next step may be an independent analysis. I’m not saying the DEP is wrong but we need to verify.”

DEP’s Shader said the department reports details of wells, permits, and inspections on its GIS oil and gas map, and is working to update the map but “does recognize the need to make it more accessible.”

The department is continually trying to improve the quantity and quality of publicly available oil and gas data, and that process will be helped by online permitting, Shader said, but that goal has been hindered by a shortage of resources.

“A decade of budget cuts and under-investment in information technology has left the agency behind the curve,” he said.

The Heinz Endowments provided funding to the Public Herald for their investigation, Heinz also provides funding to StateImpact Pennsylvania.