While global methane emissions are up, study says fossil fuels not the culprit

-

Susan Phillips

Will Von Dauster / courtesy of NOAA

NOAA researcher Stefan Schwietzke and pilot Stephen Conley prepare to take off on a research flight to measure methane emissions in Colorado.

A new study from NOAA, the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration, puts a new twist on a tricky question about the impact of increased oil and gas production on greenhouse gas emissions. Scientists have detected increased rates of methane emissions globally since 2007. That uptick corresponds to the rapid boom in U.S. shale gas and shale oil production, and some hypothesized that the two could be connected. But it turns out that the correlation may not necessarily be a cause.

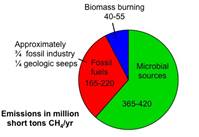

The research published Wednesday in the journal Nature found that although previous methane emissions from fossil fuel production, which includes coal, oil and gas, were significantly underestimated, the overall atmospheric increases in methane is not due to oil and gas production. NOAA, which has been measuring methane in the atmosphere since 1984, says the global increase in methane could be coming from microbial sources including wetlands, rice paddies and agricultural livestock like cows. Methane is considered more potent a greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide because although it breaks down more quickly than CO2, it traps heat 28 times more effectively over the course of 100 years.

Researchers compiled the largest database yet on global methane, which produced a truer picture of the total number of methane molecules in the atmosphere, as well as a clearer view of where that methane originated. As a result, the researchers say they’ve identified more methane from oil and gas production than previously thought, an increase of 20 to 60 percent. But that’s not enough to account for the global rise of methane in the atmosphere.

“We recognize the findings might seem counterintuitive – methane emissions from fossil fuel development have been dramatically underestimated – but they’re not directly responsible for the increase in total methane emissions observed since 2007,” said lead author Stefan Schwietzke, a scientist with the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES) at the University of Colorado Boulder, working in NOAA’s Earth System Research Laboratory.

Schwietzke says that while natural gas production has increased, the rate of methane leakage, or the amount of natural gas that escapes or is vented as measured against the amount that is captured and sent through a pipeline to market, has actually decreased from 8 percent to 2 percent in the last 30 years.

“What we found is that the absolute amount of emissions has remained constant, while production of fossil fuels has increased dramatically,” said Schweitzke.

The two percent leakage rate holds up to research conducted by Carnegie Mellon University, which measured methane leaks from both conventional and unconventional wells in Pennsylvania’s Marcellus Shale. Their results were published this year in Environmental Science and Technology.

“The two percent is in the same ballpark as what we’ve been measuring,” said Albert Presto, a professor at Carnegie Mellon University who was not involved in the NOAA research, but was the the lead investigator on the Carnegie Mellon study. Presto’s work, like the NOAA report, also found that leaks from gas sites were higher than previous measurements, in this case those recorded by state regulators.

But that two percent is significant when comparing the greenhouse gas footprint of natural gas with coal.

In 2011, Cornell University professors Robert Howarth and Anthony Ingraffea, published a controversial paper on shale gas, raising questions about the amount of methane released during production and whether those emissions cancelled out the gains from less carbon dioxide emitted at the power plant, when compared to coal. Citing a lack of data and the need for more research, Howarth and Ingraffea estimated that methane emissions from shale gas was 3.6 to 7.9 percent of total production. More research and more debates over the climate trade-off between coal and natural gas have followed. The Environmental Defense Foundation has conducted it’s own studies, working with industry to encourage plugging leaks and eliminate flaring.

In a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in 2012, EDF scientists Ramon Alvarez and Steve Hamburg estimated that replacing coal burning power plants with natural gas benefits the climate as long as the methane emissions rates of gas production stay below 3.2 percent.

“This [NOAA study] sort of suggests that they’re either at that limit or below it,” said Presto.

NOAA’s Stefan Schwietzke says different researchers have concluded that different leak rates mark a threshold when attempting to determine the point at which burning natural gas emits less greenhouse gas than coal. But he says, his results are “within the range” of what most researchers conclude burning natural gas is less damaging than coal.

Still, the NOAA researchers say the industry can and should do more to reduce methane emissions.

“Our study shows that leaks from oil and gas activities around the world are responsible for a lot more methane than we thought,” said co-author Lori Bruhwiler, a NOAA research scientist. “The good news is that fixing leaking oil and gas infrastructure is a very effective short-term way to reduce emissions of this important greenhouse gas.”

Some scientists and activists say regardless of the leakage rates, climate warming is happening at such a rapid rate that as much as possible fossil fuels need to remain in the ground while the world switches to renewable energy sources.

Although scientists have always known that microbial sources of methane represented a large portion in the atmosphere, the research could have an impact when it comes to tackling sources of greenhouse gases that are not related to fossil fuel production. Schwietzke says recent rise in atmospheric methane is from microbial sources. He says more work needs to be done to pinpoint what microbial source is the greatest culprit. Another NOAA research paper released this year points to equatorial wetlands, which have seen an increase in precipitation since 2007 due to weather patterns like La Nina. Other microbial sources of methane include ruminant emissions (cow burps for example), rice paddies and landfills. Biomass sources of methane include forest fires, and wood burning cook stoves, primarily used in developing countries.