Research flight to provide new estimates of Marcellus methane leaks

Jeff Peischl / CIRES/NOAA

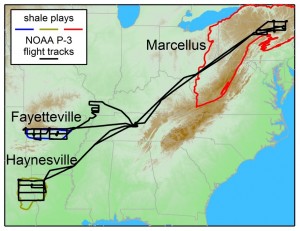

A NOAA research plane flew over the Marcellus, Haynesville and Fayetteville shale plays in June and July 2013 to measure methane emissions related to natural gas extraction.

This summer, a research plane flew over three of the largest shale gas producing regions of the country, including the Marcellus Shale in Northeastern Pennsylvania, to measure methane emissions and calculate leak rates from the wells and pipelines below.

Scientists from the University of Colorado Boulder and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration are still studying the data gathered in June and July to determine how much of the regions’ methane might come from natural gas operations, but the results promise to provide the first published “top-down” estimates of how much methane is leaking during gas extraction from the Marcellus, Fayetteville and Haynesville shales.

Top-down estimates calculate a region’s methane or other pollution based on concentrations measured in the atmosphere, while bottom-up, or inventory, estimates determine large-scale emissions by measuring leaks at some sources on the ground, like well sites. Scientists using both approaches gave overviews of their new work at the American Geophysical Union fall conference in San Francisco on Wednesday.

Methane is a more potent but shorter-lived greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide. Burning natural gas instead of coal at large power plants helped the U.S. reduce its energy-related carbon emissions last year to the lowest level since 1994, but excessive methane leaks could dampen those climate benefits.

Jeff Peischl, a scientist with CU-Boulder and NOAA’s joint Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences, said his group’s flyover estimates from this summer will be compared with inventory estimates for the three shale regions. Results from the two types of measures sometimes differ. For example, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s inventory estimates that 1.5 percent of methane in the whole natural gas supply system escapes through leaks, but recent top-down studies in Western U.S. oil and gas production basins have found higher localized leakage rates.

Gabrielle Petron, a scientist at CIRES, cautioned against using a top-down calculation in one region to make assumptions about others. She said new measurements should be used to make sure estimates better reflect reality.

Advanced on-the-ground emissions studies, like one recently published by University of Texas at Austin researchers, also help identify specific sources of leaks to fix. The UT study found that methane leaks during natural gas extraction are in line with the EPA’s current estimate for that portion of the natural gas system. But the researchers found that emissions during well completions were much lower than EPA estimates (in part because most sites captured or controlled emissions to meet new regulations) while gas leaks from valves and other equipment on well pads were much higher.

David Allen, the study’s lead author, said a small fraction of the total number of valves leaked enough to dominate the emissions for that type of equipment, for example.

“These are complex sectors involving lots and lots of different sources,” he said. “What are the emissions coming from each of these individual sources? Which of these sources are most important?”