Chesapeake Energy: Everything You Need To Know About The ‘World’s Biggest Fracker’

-

Joe Wertz

This post was co-reported by StateImpact Pennsylvania’s Scott Detrow and StateImpact Texas’ Terrence Henry.

If you’ve been hearing a lot about Chesapeake Energy Corporation and its eccentric CEO Aubrey McClendon as of late, you might have some questions. What is this company? Who is McClendon and what’s the deal with his wine and antique map collection?

To tackle some of those questions and more, StateImpact reporters in Oklahoma, Pennsylvania and Texas teamed up to create a reading guide to Chesapeake Energy’s recent financial woes.

What is Chesapeake Energy?

It’s a drilling company, the second-largest natural gas extractor in the country.

Chesapeake is an energy producer that focuses on unconventional onshore oil and natural gas plays in the U.S. The company’s roots are in natural gas. However, near-record low prices for natural gas have forced the company to shift focus to oil and production of other valuable liquids.

Chesapeake employs about 13,000, according to the company’s Securities and Exchange Commission filings. About 4,600 people work at the company’s corporate headquarters in Oklahoma City. Chesapeake also has regional corporate offices in Texas, West Virginia and Louisiana, as well as 60 field offices throughout the U.S.

As recent news reports have pointed out, Chesapeake is also something of an investment firm. The company regularly flips the land it purchases, selling it to other drilling companies.

Chesapeake is an aggressive spender and has continued to expand, despite the fact that natural gas prices are at a ten-year low. That expansion is a big reason why the company holds more than $13 billion in debt.

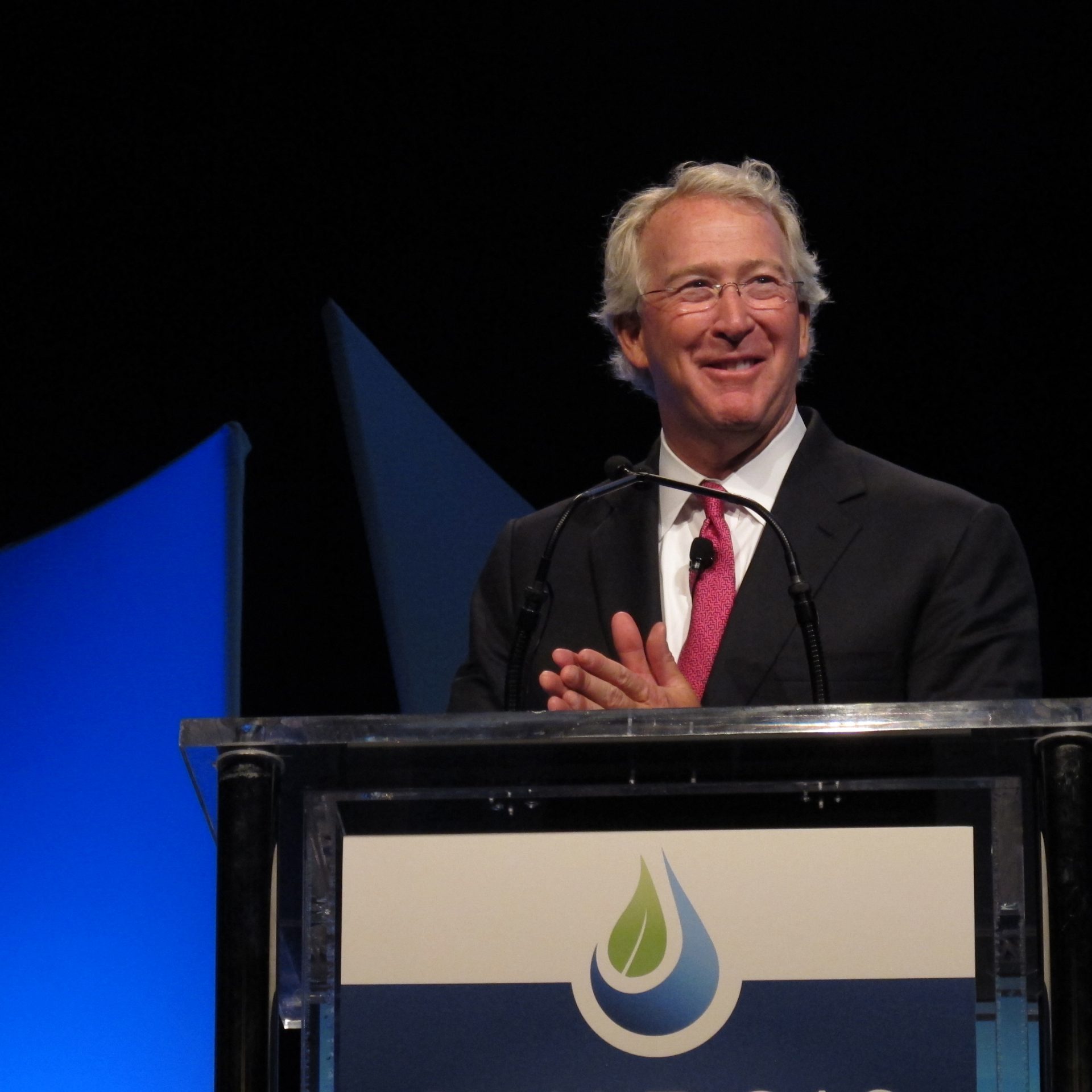

Who is Aubrey McClendon?

Aubrey McClendon is the founder and CEO of Chesapeake Energy. Until earlier this month, when news reports began questioning his business dealings, he also was the chairman of the company’s board.

McClendon started working on his own as a landman — the guy who goes door-to-door signing land leases for energy companies — in 1982. In 1989, McClendon and Tom Ward — now CEO of SandRidge Energy — pooled $50,000 together and founded Chesapeake, a natural gas-focused company that played a cutting-edge role in the country’s current hydraulic fracturing boom.

McClendon is something of a natural gas evangelist, and is happy to mix it up with anti-drilling activists. Of Chesapeake, he once bragged to Rolling Stone that “we’re the world’s biggest frackers.” Here’s what he told the Wall Street Journal, when the paper asked about drilling opponents calling for hydraulic fracturing moratoriums: “You want to go ban fracking for a year? Knock yourself out.” Limiting the supply of natural gas would only drive up its price, he said, and that “would be marvelous for our share price.”

McClendon has a wide range of tastes and business interests. He loves fine wine. In fact, McClendon’s interview with Rolling Stone was conducted over a $400 bottle of Bordeaux. And McClendon owns almost 20 percent of the Oklahoma Thunder basketball team, where he has a courtside perch.

McClendon and Chesapeake have been in the hot seat before. When natural gas prices plunged in 2008, the company’s stock price followed. McClendon had borrowed heavily against his shareholdings, and was forced to sell 30 million shares — more than 90 percent of his holdings — to meet margin calls. This erased most of McClendon’s $2 billion fortune, Forbes reported.

But the company wanted to reward McClendon for $1 billion in joint venture deals he helped secure. So the board gave him a $110 million pay package. Seventy-five million was for well interests (more on that later), and $20 million was for a stock grant. The company also handed over another $12 million to buy McClendon’s collection of antique maps from the 19th century.

The map purchase didn’t sit well with many Chesapeake shareholders, some of whom sued the company demanding reforms to its compensation practices. In a settlement, McClendon agreed to buy back the maps, with interest.

I hear he’s taken out some unconventional loans.

That’s an understatement.

Brett Deering / Getty Images

Chesapeake Energy CEO Aubrey McClendon and Oklahoma City Thunder owner Clay Bennet courtside during an Oklahoma City Thunder game.

In March, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reported that Aubrey McClendon was taking out loans against the company’s West Virginia holdings. This month, Reuters expanded the story by reporting that this was happening in multiple states: McClendon has taken out more than $1 billion in loans, using Chesapeake’s land holdings as collateral. And as Reuters documented, he is using that money to expand his holdings in those very same wells. The circular loans — and the fact they weren’t disclosed to shareholders — raised questions about whether McClendon’s mixing of his personal and business dealings constitute a conflict of interest.

McClendon was able to purchase personal stakes in Chesapeake’s wells through an initiative called the “Founder Well Participation Program.” Chesapeake shut the program down shortly after it became public.

McClendon didn’t see anything wrong with purchasing personal stakes in his company’s wells. “American business would be run better today if there was more alignment between CEOs’ interest and the company,” he told the Wall Street Journal before Chesapeake shut the Founder program down. “For example, would the financial crisis of 2008 have occurred if the CEO of Lehman and Morgan Stanley and Goldman and Citibank had to take a very small percentage of every mortgage-backed security … or every loan they made?”

What other creative borrowing has gone on?

McClendon and Chesapeake won’t be paying back many of these loans using money. Instead, they’ll be using oil and natural gas, in an exchange called a “variable production payment,” or VPP.

Arthur Berman, the head of Labryth Consulting, a Houston-based geological consulting firm, is a leading critic of McClendon’s arrangement. He says the cash-for-gas exchange is overly complicated. “So he’s borrowed against the wells that will have future production, plus he’s also agreed to give a certain amount of that production to somebody else who gave him money up front.”

While he was CEO and chairman of Chesapeake’s board, McClendon was also running a lucrative side business with Ward: a $200 million private hedge fund called Heritage Management Company LLC. Here’s what Reuters’ investigation revealed:

The hedge fund listed Chesapeake’s headquarters in Oklahoma City as its mailing address, documents show. Heritage’s staff included an accountant who was simultaneously employed by Chesapeake. The fund also earned McClendon and Ward management fees and a cut of profits from outside investors.

Some analysts and corporate governance experts have said that the arrangement amounts to a front business for Chesapeake, because the fund traded the same commodities Chesapeake produced. Critics have also said the arrangement created a conflict of interest for the two businesses, whether real or apparent.

What’s this about cash flow?

When news of the loans came out, reporters began taking a closer look at Chesapeake’s finances. And they made some interesting discoveries: Chesapeake owes a lot of money to a lot of people: The company currently holds more than $13 billion in debt.

That’s primarily because Chesapeake has continued to aggressively expand its business operations and land holdings, even as natural gas prices have plummeted thanks in part to increased domestic supply brought on by the fracking-fueled drilling boom Chesapeake helped start. In a way, Chesapeake is a victim of its own success.

The company lost $71 million in this year’s first quarter, and had to scale back its cash flow estimate for this year from around $5 billion to under $3 billion. Last month, the company borrowed an additional $4 billion. Chesapeake said the increase was the product of strong demand from investors willing to buy its debt. “We appreciate this strong vote of confidence from investors,” McClendon said in a statement.

What has all this meant for the company?

It’s meant several things, none of them good: falling stock prices; a lower credit rating; and the interest of Securities and Exchange Commission investigators.

The SEC probe — an “informal inquiry” — was launched in early May, after the Founders Well Participation Program and McClendon’s loans first came to light.

Chesapeake’s stock prices have suffered due to the ongoing scrutiny. Its stock was trading for around $20 a share at the beginning of May, but dropped to $13.55 — its lowest level since early 2009 — on May 17. Since then, the price has rebounded. Chesapeake stock opened trading on Tuesday at $16.53.

In April, Standard & Poor’s downgraded Chesapeake’s credit rating. Last week, S&P reduced it again, to BB-, a rating that S&P says is indicative of a company facing “major ongoing uncertainties.” Here’s how the AP summarized the decision:

The credit ratings agency believes that Chesapeake will struggle to generate enough cash to pay off its debts as natural gas prices plunge. Standard & Poor’s also noted that the “mounting turmoil” from CEO Aubrey McClendon’s personal financial dealings could make it tougher for the company to raise money in the future.

How are employees affected?

Thousands of Chesapeake workers have retirement portfolios heavily invested in company stock, which reached a one-year low on May 11.

Chesapeake stock comprises about 38 percent of the only 401(k) plan available to most employees, “far above the 10 percent many plan consultants advice,” Reuters reports. And roughly 4,000 employees are restricted from selling shares the company puts into their retirement portfolios because they’re shares Chesapeake deposited to match the employee’s contribution.

So will this impact drilling operations?

It will.

McClendon says Chesapeake is going to focus on drilling itself — not land deals — in order to help raise more money. He told investors last week that Chesapeake will become a “more balanced liquids-focused producer.”

That likely means an increased focus on shale formations that produce“wet gas” — material containing compounds like ethane and propane, which can be sold for higher prices than natural gas. For Pennsylvania, this means a possible shift in drilling activity away from Chesapeake’s northeastern holdings, and more of a focus on the southwest, as well as Ohio’s Utica Shale.