Mining Student Data To Keep Kids From Dropping Out

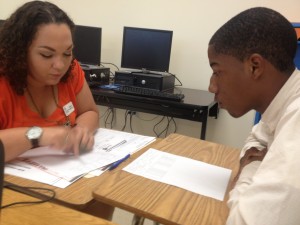

It’s report card day at Miami Carol City Senior High, and sophomore Mack Godbee is reviewing his grades with his mentor, Natasha Santana-Viera.

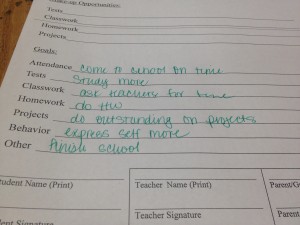

The first quarter on Godbee’s report card is littered with Ds and Fs. This quarter, there are more Cs and Bs. He’s got an A in English.

“Congratulations on that,” says Santana-Viera. “When you need help, do you know where to go?”

“Straight to y’all,” says Godbee.

Lots of teachers talk to their students about their report cards. But this conversation is the result of a school initiative to monitor student data—looking for dropout risk before the obvious signs that a student is struggling. It’s part of a national program called Diplomas Now, which operates in several schools in Florida.

Talking to Godbee about his report card and his goals for the next quarter is just one piece of a strategic plan to make sure he stays in school.

Florida lawmakers are currently considering a proposed bill that would, among other things, create similar early warning systems in middle schools to flag students who are at risk of dropping out.

CONNECTING THE DATA

“It’s easy to collect information and look at information,” says Scott Crumpler, the South Florida field manager for Diplomas Now. “But what you do with that information is the key element and key component of our program.”

For decades, the Florida Department of Education and schools across the state have collected a massive amount of information about students—grades, attendance, demographics, behavior, test scores. That information has been used to assess how well a school or a district is doing.

But the Diplomas Now program—which had representatives speak to the Florida House K-12 Subcommittee last November—takes student data and predicts which students are in danger of not graduating. The kids identified are then connected with support services.

At Carol City, those connections begin in a conference room nicknamed the War Room.

Once a week, teachers, sports coaches and administrators gather around a heavy wood table in the War Room to discuss students who are in trouble. They’re joined by partners from the organization Talent Development—which analyzes student data, City Year—which provides mentors, and Communities in Schools—which helps get kids support like health care and social services.

An analyst crunches data on student attendance, behavior, and performance in math and English. Then, based on some dropout risk studies from Johns Hopkins University, she flags kids who are on a downward trend.

In the War Room meetings, those students’ dossiers become a slide on a PowerPoint. The educators at the table then talk about how to turn things around for the student.

At a meeting one Tuesday in February, the student projected at the front of the room has been flagged for missing class and slipping grades.

A facilitator asks if anyone has insight into what’s going on with the young man.

“He came to me last week and said, ‘I haven’t had anything to eat all day,’” says a teacher.

“If that happens again, and he says that he’s hungry, we keep snacks in the office,” offers another.

One educator chimes in that the student spent a week-and-a-half living in a car this semester.

Somebody suggests putting him in touch with homeless services. A teacher he doesn’t have offers to get him a planner so he can stay on top of his classwork while things are in flux at home. A sports coach volunteers to be the point person.

THE CORE OF THE PROBLEM

“If we don’t get to the core of the problem, we can’t teach them,” says Tracy Troy, a math and special education teacher who has been at Carol City for 14 years.

When the Diplomas Now program was introduced three years ago, Troy was apprehensive about getting involved with students’ problems outside her classroom.

“Not that I don’t care, but I care too much. It weighs on you,” says Troy. “Those are your children while you’re here.”

Now, she says, the War Room meetings help her help the kids.

It costs about $600 per student to run this kind of Diplomas Now program. Currently, the initiative at the Carol City site is mostly supported by grants. The U.S. Department of Education has given Diplomas Now $30 million to conduct a randomized, control study of how the model works. The project also has $12 million in backing from the PepsiCo Foundation.

When it comes to return on investment, supporters of early warning systems often point to a Northeastern University study that found high school dropouts cost taxpayers an average of $292,000 over the course of a lifetime.

Last school year, a third of Carol City students who were flagged for missing school got back on track to graduation. Two-thirds of the students who were having behavioral problems made a turnaround.

GETTING BACK ON TRACK

Sammy Mack / StateImpact Florida

Sophomore Mack Godbee has been setting new goals. It's part of the Diplomas Now program.

Mack Godbee, the sophomore pulling up his grades, is one of those students making a comeback after getting flagged by the Diplomas Now program.

If his name hadn’t been identified, says Godbee, “I think I would have ended up dead.”

Ended up dead, he says, because he spent a lot of time on the street. When his dad left, Godbee says he wanted to show his mom they didn’t need him. He started selling drugs.

He was six years old.

He says by the time he got to high school, he was affiliated with a gang. He skipped classes. Didn’t study. He was angry all the time.

Which would be easy to miss.

Godbee is soft-spoken, thin, and on the day of the report card conference, he’s dressed in a soft cotton oxford buttoned at the neck.

But earlier this school year, after looking at the data, Santana-Viera—Miss Santana, he calls her—sat Godbee down and asked: Are you okay?

“I sat right there and I thought about it, like, am I really ok?” says Godbee.

For the first time in his life, he said, “no.”

“I don’t want to be the person I am now; I want to be a different person,” says Godbee. “I want to be that kid who makes straight As and Bs on his report card. Be in school every day on time. Be on that honor roll list. Go on field trips.”

“The point of all this isn’t to collect data; it’s to change what’s happening for individual kids,” says Paige Kowalski, a state policy director for the Data Quality Campaign—a group that advocates for better use of all that student information the states collect.

About 20 states have developed early warning systems like the one proposed in Florida.

Kowalski says schools could take a cue from the medical field.

“We don’t just put out reports saying the hospital lost all these patients and saved these people,” says Kowalski. “They actually look at it and say, ‘what can we do better?’”

At Carol City, the answer is to try to find kids in trouble before it’s too late.