Why The Debate Over Cursive Is About More Than Penmanship

Neyda Borges / WLRN

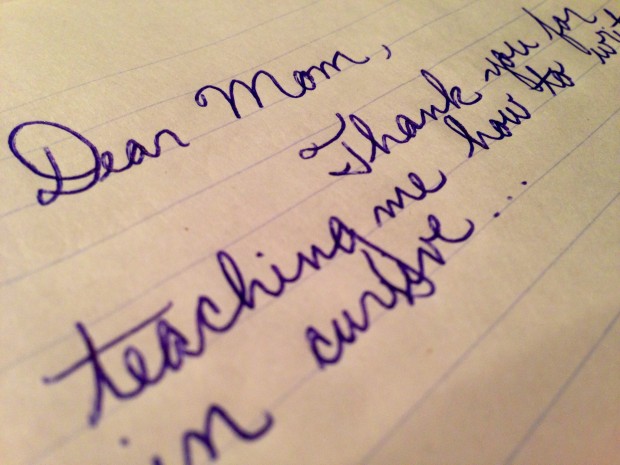

Most school districts no longer require students to learn how to write in cursive. Since the 1970s, fewer and fewer people see the importance of curlicues.

Every October, high-school students across the country take the PSAT, or Practice SAT, a standardized test developed by College Board that provides high school students a chance to enter scholarship programs and gain access to college and career planning tools.

But, it wasn’t the algebraic equations that terrified the kids. It was the cursive.

Seriously.

As the kids filled in their identifying information, they came to a section that asked them to copy a pledge promising not to cheat – in cursive – and then to sign their names.

“Miss, what do they mean by ‘sign your name’?” one student asked.

“You know, the way that you write your name on important documents, like contracts or checks.”

Questioning stare. “Like, in cursive?”

“Yes.”

I have never seen so many stunned teenagers, paralyzed, gripping their pencils, gulping. It took one child a full five minutes to copy the roughly 25 words and sign his name.

“I just wrote it normally and then went back to connect the letters,” he later said.

This is not new. A 2010 Miami-Dade County Public Schools report found that found that cursive instruction has been slowly declining nationwide since the 1970s.

In the high-tech world of high-stakes tests, educators are working to prepare students for the FCAT, end-of-course exams, AP and AICE exams, college admissions and a successful future in which computer and typing skills are essential. In a classroom where school grades and teacher pay depend on student test scores, and educators are asked to do more and more on leaner and leaner budgets, making the time to teach fancy curlicue letters just does not seem imperative.

And that trend will only continue as the Common Core standards, which do not require cursive instruction, continue to roll out.

“The Common Core State Standards allow communities and teachers to make decisions at the local level … so they can teach cursive if they think it’s what their students need,” said Kate Dando, a spokeswoman for the Council of Chief State School Officers, which promotes Common Core.

But not all of the kids in my class were lost. There was one who copied the statement in seconds, and then sat up straight, patiently waiting for his classmates to finish. After the test I asked him if he learned to write in cursive in elementary school.

“No,” he said. “My mom taught me because she thought it was important.”

And that is the true issue. The dilemma is not truly whether the “art of cursive” writing is important. The dilemma is the growing chasm between kids whose parents have the money, education, and time to enrich their children’s learning, and those that don’t.

Cursive isn’t the only victim of standardized testing. Students no longer learn grammar. The reigning educational philosophy of the last 30 years stressed the writing process, not the final product. Researchers questioned the necessity of recognizing hanging participles or conjunctions. In the career world, they argued, people would never have to identify those. Furthermore, they contend, grammar is implicit in reading. As kids read, they will pick up all of the grammar that they need.

Besides, why do teachers need to correct errors in obnoxious red ink when all word processing software contains grammar- and spell-check programs?

That is, of course, when kids read — outside of school. When they have books in the home. When their parents read to them. When there are computers in the home. In other words: children who live in more affluent homes are more likely to learn outside of school, widening the achievement gap.

A Stanford University study finds that the achievement gaps begin as early as 18 months. By kindergarten, it can be a two-year gap. Poor kids — not to mention immigrants and children whose parents do not speak English — start so far behind when school begins that they never catch up.

It is true that college students are more likely to type out their notes on laptops and tablets than to write them with pen and paper. Fewer people write checks every day, opting instead for credit cards and e-banking.

Elementary-school students use calculators. After all, when will they ever be far from a smartphone that can add, subtract, multiply and divide?

The difference is that some kids will learn. Some of their parents and grandparents will teach them those intricacies and formalities that the school curriculum leaves out. Some of them will fill in the gaps.

Some of them won’t.

Neyda Borges, a University of Miami graduate, lives and works in Miami Lakes, where she teaches English and journalism at Miami Lakes Educational Center. She is the Language Arts Department chair, The Silver Knights Coordinator, and advises the school’s newspaper and yearbook. Borges was selected the Region I Teacher of the Year in 2011 and was one of the five finalists for the county’s Teacher of the Year.

Borges is a member of the Public Insight Network, an online community of people who have agreed to share their opinions with The Miami Herald and WLRN. Become a news source for WLRN by going to WLRN.org/Insight.