For Homeless Students, College Enrollment Means A Roof Over Their Heads

It is college-application season, which means high-school seniors across the country are scrambling to write personal statements, list all their extracurricular activities and take the SATs.

Sierra DuBose is one of those seniors, enrolled at Miami Edison Senior High, but she is also one of almost 7,000 kids in the Miami-Dade public-school system who are homeless. That’s about 2 percent of the student population.

Sierra currently lives in a shelter for women called Lotus House, on the edge of Overtown.

The walls of her shared bedroom are painted bright pink, her favorite color. Her backpack lies on her bed, stuffed to the gills with homework and articles from all the clubs she’s in: yearbook, J-ROTC, and the school newsletter to name a few. The apartment has a full kitchen, which she hardly uses, and a special perk: a computer.

“It’s small but once you get used to it, you just find out that where you reside or where you come back to at night doesn’t have to be big,” Sierra says. “As long as you have a bed, it’s cool.”

The Lotus House provides food and staff support to help with job searches, counseling and computer training, among other services.

Sierra found the shelter with help from Project Upstart, a program that educates teachers and administrators on how to address the needs of homeless students. One of the biggest challenges of addressing those needs, though, is identifying who is homeless.

“’Homeless’ means students who are in a shelter, living in the street, in a car or in a park, in the home of somebody else, [which] means that they cannot afford to live in their own home [what’s called ‘doubled-up’] and living in motels or hotels,” says Debra Albo Steiger, Project Upstart’s manager.

A majority of students are in doubled-up situations, but about 300 are unaccompanied kids living on their own like Sierra.

Mihail Halatchev / WLRN

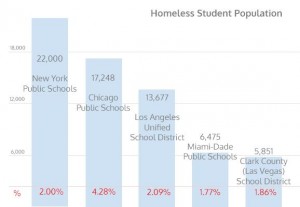

This graph shows Miami-Dade's population of homeless students in comparison to other school districts across the country.

Until now, it’s been up to teachers and administrators to find students who don’t have permanent homes. But starting next month, the school district, along with the Homeless Trust, will be out in the community looking for those students and counting them — the first comprehensive count of its kind in Miami-Dade County.

“We’re hoping [the Department of Housing and Urban Development] will recognize that we do have an issue and we’ll be able to have more specialized services for unaccompanied youth,” Steiger says.

She says money from the federal government could be used to create housing for students, who, given their age, probably shouldn’t live in regular shelters.

But counting and providing housing is only one aspect of challenge. Lack of stability can affect a student’s academic performance.

“Even though I’m kind of ahead of the game [now],” Sierra says, “it took a long time for me to catch up with everybody else because when you’re in [a transient] situation you don’t really focus on school. That’s not your main priority.”

A school program called College Summit helped her reorient that priority. The program teaches students from difficult backgrounds learn, among other college-related things, how to work their personal stories into their applications. Vivien Carter runs the Florida branch.

“The beauty of the curriculum is helping them to advocate and learn what it means to advocate for themselves,” she says.

Sierra’s situation has forced her not only to become her own advocate, but to think seriously about her future. If she doesn’t, come graduation, she might not be sleeping with a roof over her head.

At this point though, she’s not too worried about letting that happen. She has been accepted to two colleges already and plans to apply to few more. Now she’s trying to figure out if she can pay for the education. If she can’t, she’s considering the military, which would allow her to travel for the first time.

“Furthering my education is key to me. In this stage of my life I think that’s the best way I can get out of the situation I’m in right now,” Sierra says.