Pipelines’ paths remain a risky mystery beneath our feet

-

Susan Phillips

This story began with a simple task: Let’s make a pipeline map!

Everyone wants to know where all the new Marcellus Shale gas pipelines are or will be. The new proposals have been piling up. Many have poetic names like Atlantic Sunrise, Mariner East, and Bluestone. There got to to be so many they started to get numbers: Mariner East I, Mariner East II.

Here at StateImpact Pennsylvania, try as we might, we couldn’t keep track of them all in our heads. We also wanted to map all the smaller lines, and the lines that may have been there for decades, which everyone tends to forget about.

The Wolf Administration estimates that 30,000 more miles of new pipelines will be built in Pennsylvania within the next two decades. So, where will they be?

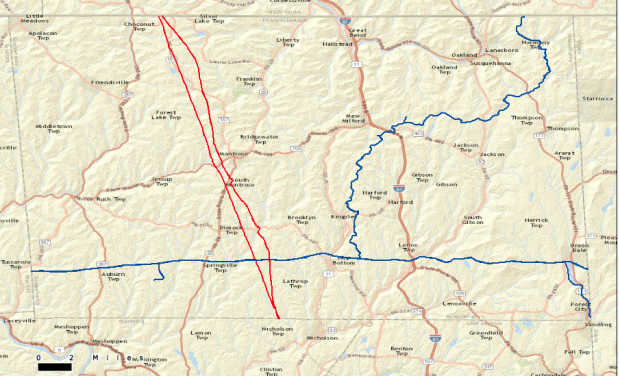

screenshot / Pipeline Hazardous Material Safety Administration.

This map of interstate pipelines currently running through Susquehanna County is all that’s available to the public on PHMSA’s website.\

Pipeline companies know exactly the routes for all the pipelines they maintain or plan to build. But they aren’t required to share that information with public.

Instead they release vague maps with colorful lines swooshing across Pennsylvania, showing where a proposed line might go.

We spoke with our resident map maker, who told us that wasn’t good enough. She needed geospatial data, the kind of thing that in this high tech digital world means plotting the line along its actual path, instead of just drawing a line that approximates the path.

We took a look at all the plans submitted for new pipelines, but they were just drawings, without data. We checked with the Pipeline Hazardous Material Safety Administration (PHMSA), which has a national map of the major interstate pipelines. But again, just a drawing, no geospatial data available to the public, and by the way, don’t even try to do a right-to-know request. Interstate pipeline maps are exempt from that in this post-911 world.

Then we contacted Mark Smith, who runs a map-making company called Geospatial Corporation. We told him what we wanted to do: map the web of pipelines beneath our feet. He laughed at us.

“Well, it’s not universally mapped,” said Smith. “In fact it’s probably the last piece of infrastructure out there that’s not mapped.”

Wait, this stuff is highly flammable right?

“Yes.”

Smith is in a good business as a pipeline mapper these days. He gets called in by utilities and companies that want to know not only where their lines run exactly, but where other lines might intersect. The companies don’t want their people to get blown up when doing work on the line. Some of these pipelines were built more than 100 years ago. And the maps that do exist, which he says could have been based on visible landmarks that aren’t there anymore, just aren’t that accurate.

Lindsay Lazarski / WHYY

A pipeline from a Seneca Resources gas well before getting installed along a road in the Loyalsock State Forest.

“A set of drawings back then, it might have been for a water line,” said Smith. “Now there are sewers, there are fiber optics, there are high pressure gas lines, there are a multitude of utilities that have been put in like spaghetti underground with really no regard to positioning.”

Even when it comes to interstate pipelines, the large ones that carry lots of gas at high pressure across multiple states, those are only required to be mapped within 500 feet of accuracy. So even if the public did have access to the PHMSA maps that give the best approximation of a pipeline’s path, it could still be off by 500 feet.

Today, Smith says he’s got a system that can map all these lines with the exact GIS coordinates. But still, he says even the relatively recent pipelines are not always where they are supposed to be.

“We’ve been called into a multitude of projects where within one right-of-way there was supposed to be a pipeline installed ten years ago. Workers come in to that right of way, they move over what they think is 50 or 75 or 100 feet, they drill in another line and they end up hitting the original pipeline that’s supposed to be 75 feet away. That happens a lot.”

And it happened a couple of weeks ago in Armstrong County, north of Pittsburgh, where a routine construction job put a man in the hospital. He was in a bulldozer digging out a route for a new gas pipeline when he struck another unmarked pipeline full of natural gas. Pictures of the explosion show a crater where the bulldozer sits, charred and mangled. The man who was running that machine is now in the hospital with 70 percent of his body burned.

Turns out the worker hit a medium-sized, 12-inch line carrying gas at a pressure of 60 PSI. His company did what they were supposed to do before digging, contact the state’s Pa. One Call service to check whether it was OK to dig where it planned.

One Call gave the company the all clear. Problem was: The line that blew up wasn’t mapped. The Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission is investigating, but it’s unclear whether or not current laws would have required that line to be mapped at all.

And it turns out even the larger interstate pipelines that are supposed to be mapped sometimes don’t show up on official government documents, like the PHMSA map.

Susan Phillips / StateImpact Pennsylvania

Joe Kulick, emergency manager for Durham Township in Bucks County says he kept getting put on hold after calling the number on the pipeline sign. It went to a power station in New Jersey, where no one was able to give him any information about the pipeline running through his township.

Joe Kulick is the emergency manager for Durham Township in Bucks County, where about 1,100 people live along the Delaware River.

A few months ago, Kulick tried to get information on what looks to be a major pipeline running through the township.

“Every street crossing it’s marked, hazardous pipeline, with that phone number that goes nowhere,” he said.

He called that phone number posted on the sign. A lot.

Here’s how he says the conversation went.

“Hi, my name’s Joe Kulick, I’m the emergency manager of Durham Township and I’m trying to get some information on this pipeline. And the guy said, ‘Hold on!’ That happened about three or four times that day. So I waited, got put on hold and I said, ‘Hi, you just put me on hold’ and he said ‘Oh, we must have gotten disconnected,’ he put me on hold again. Nothing.”

This run-around happened for day, launching Kulick on a month-long quest to find out more information about that darn pipeline.

“Funny part is when people didn’t know what I was talking about and they took the old put you on hold and never came back routine and there’s no way out of it,” he said. “It’s a dead end. You can’t push buttons. Try pushing operator and they never come back so I had to redial the number and start all over again and quickly tell somebody don’t put me on hold.“

After 9-11 the feds limited the public’s access to information on pipeline routes. But as an emergency manager, Kulick qualified as a government official.

“So I clicked on the government officials’ link,” he said. “And about a month later I got an actual password. And I got on the site and it was the exact same site as the civilian site. So I don’t know what that was about, I could get no more information.”

Luckily, his other phone calls paid off.

Kulick says he finally got some help from a friendly guy at Sunoco, the company that used to own the pipeline. It turns out that nothing is flowing through the pipe today, it’s inactive. He was able to add it to the map of the township. But he still wonders how he would find out if it becomes active again.

“I don’t like the fact that it’s not on the maps,” he said. “If you look at these federal maps its not there; there’s no such pipeline.”

Susan Phillips / StateImpact Pennsylvania

Joe Kulick, Durham Township Manager, eventually plotted the line by using aerial photos on Google Earth.

Kulick is not the only person who has decided to tackle the mysterious job of pipeline mapping.

About 100 miles north of Durham Township lies the drilling mecca of Susquehanna County. On the corner of two country roads is a house that lies 2,000 feet from two new Marcellus Shale pipelines. The woman who lives there is Meryl Solar.

Yes, Solar.

“Like the other kind of energy,” she said. “I was born with that name, so it’s not something I just picked up but it’s something I agree with.”

Unlike me, Solar actually figured out how to make a pipeline map.

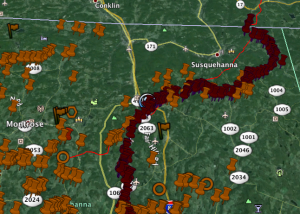

Using Google Earth, she plotted out all the planned natural gas infrastructure that comes along with the gas wells, including compressor stations and pipelines. On her map of Susquehanna County, each piece of natural gas infrastructure has its own color-coded thumb-tack.

“I did this because of conversations I had with people, [who] kept repeating the same line – it’s non-invasive, it’s non-intrusive, it’s not going to change your life, don’t worry so much, it just means a lot of money for everybody. And in my mind that can’t be.”

Solar even plotted the smaller, unregulated pipes running from the wellhead. To do that, she used permits issued for stream crossings.

“I banged my head against the wall,” she said. “I think it It took me eight months. I compiled a list that I knew of that I got from Pa. Bulletins because they have to make announcements somewhere. But it’s just so obscure that normal people will not find them. Right?.”

Right. It’s pretty amazing what she was able to do. The Pennsylvania Bulletin is the official weekly state list of all the new rules and permits issued by every state agency. Searching it is tedious. But by scouring the Bulletin for those stream-crossing permits, Solar may have compiled the most accurate pipeline map of Susquehanna County.

“See this red line here is the Constitution Pipeline, which will be built next to the Bluestone, and that’s 2000 feet behind my house,” said Solar as she pointed to the map on her computer. “In fact we got this lovely brochure from the Bluestone people, DTE, talking about our shared responsibility for their pipeline. My shared responsibility for their pipeline is noticing potential risks of an explosion.”

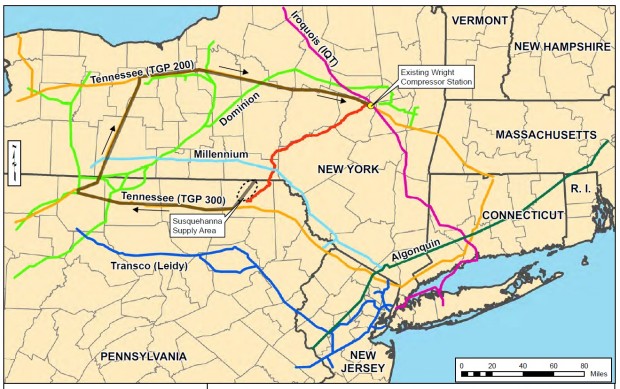

The dotted black circle shows the gas supply area in Susquehanna County. The red line is the path of the Constitution Pipeline. This is what’s available from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, which is the agency that regulates construction of new interstate pipelines. FERC

The brochure talks about odors from leaking gas pipes.

Left to itself, natural gas doesn’t smell like anything. That odor you smell when the pilot light is out on your stove is called mercapton. Companies are required to put that nasty smelling compound in their pipelines so people can smell when its leaking. But there’s an exception. If a pipeline runs through areas with little or no population, a so-called “Class One” line, no mercapton is required.

“We won’t smell anything,” said Solar. “It’s odorless and colorless. Because in a class one area for pipelines, there’s no oversight.”

Although interstate pipelines in rural areas are regulated by the federal government, they don’t have to have mercapton in them.

screenshot/Meryl Solar

A screenshot of a pipeline map created by Meryl Solar using Google Earth and DEP stream crossing permits.

And when it comes to all the smaller pipelines that do not cross state lines, Solar is right, there’s no regulation. No state, federal or local authorities provide oversight.

And again, the interstate lines only have to be mapped within 500 feet of accuracy.

That could change soon. The Pipeline Hazardous Material Safety Administration is working right now to update its rules. It wants pipelines to be mapped within five feet of accuracy. Industry groups have agreed to improvements but have proposed 50 feet instead of five.

The Interstate Natural Gas Association of America says having to re-do maps to within five feet of accuracy would be too expensive. In comments made to PHMSA regarding new mapping proposals, INGAA executives said the technology does not yet exist, and trying for five feet could result in bad data that would do more harm than good. INGAA also surveyed first responders, the majority of whom told them that they don’t rely on PHMSA’s maps and instead cultivate relationships with pipeline operators in their area in order to get good information.

In part 2 of this series, we’ll tell you about one Pennsylvania county that has bucked the trend on pipeline mapping. And why having bad maps can result in devastating consequences.

Katie Colaneri contributed reporting to this piece.