Caption

Joe Wertz / StateImpact Oklahoma

Caption

Joe Wertz / StateImpact Oklahoma

Joe Wertz / StateImpact Oklahoma

Brothers and business partners Fred and Wayne Schmedt stand in their family's wheat field near Altus in southwest Oklahoma.

Four years of extreme drought has withered the agricultural economies of southern Great Plains states like Oklahoma, where farmers are bracing for one of the worst wheat crops in state history.

And Oklahoma’s withered wheat harvest could have national consequences.

Wayne Schmedt adjusts his faded blue cap and crouches down in a wind-whipped field near Altus in southwest Oklahoma. His brother and business partner, Fred, grins and waits. The jokes start before the dusty rain gauge is pulled from the cracked dirt.

“We don’t have any use for this so we’ll give it to you as a souvenir,” Wayne says.

Gallows humor is key to surviving as a farmer, especially one in Great Plains states like Oklahoma. Here, summers are hot and dry. Spring rains often drown fields in flash floods. And a late freeze can kill off what’s left. It’s a cruel joke. Fred Schmedt looks out on his field then down at his legs and laughs.

“What would you call that, high shoe-top high? In a normal year — a really good year — it’d be thigh-high,” he says. “So we’re looking at plants that are 6 to 8 inches tall versus 24 to 30 inches tall.”

In a good year, Oklahoma produces 120 to 140 million bushels of wheat. The U.S. Department of Agriculture forecasts this year’s crop will be half as big. Jeff Edwards, a small grains extension specialist at Oklahoma State University, says even that will be a struggle.

”It’s going to be one of our smallest wheat crops ever,” he says. “There’s not a lot you can do with this extreme of drought.”

A late freeze in mid-April contributed to the problem, but Edwards says drought has done the most damage. In Oklahoma, the most productive regions of the state have been smothered in near-constant drought conditions. And climate change means such droughts are likely to continue in the Southern Great Plains, scientists warned in the federal National Climate Assessment released in May 2014. Agriculture is particularly vulnerable in this region, researchers concluded, and could bring markedly lower crop yields if farmers and government officials don’t adapt and collaborate on ways to respond.

U.S. Department of Agriculture/U.S. Drought Monitor

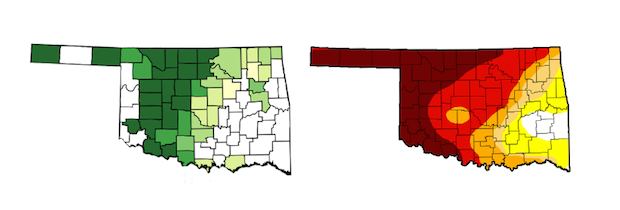

In Oklahoma, drought and wheat production coexist. The map on the left shows the concentration of winter wheat planted per acre in 2013. The map on the right shows drought intensity on May 20, 2014.

Wheat is Oklahoma’s No. 1 cash crop, and the withered harvest could have dramatic effects on community economies. The average annual value of Oklahoma’s wheat crop is around $644 million, says Phil Kenkel, an agricultural economist at Oklahoma State University, but he says that calculation doesn’t factor for “indirect” and “induced” effects of wheat revenues.

The impact is profound, but Edwards says it’s hard to factor for the wide variety of jobs and businesses — equipment sales and maintenance, gas stations, food and other service companies — that that rely on a successful wheat harvest.

“In rural Oklahoma, they make most of their money off the wheat that they bring in,” he says. “If they’re not bringing in wheat, they’re not making money. It’s hard for them to keep people employed.”

Back in his family-owned field, Fred Schmedt plucks a stunted stalk and threshes the head by hand to see if any seeds have survived. He talks about a local repairman who specializes in patching tractor and combine tires during harvest who won’t have much work if there’s no wheat to thresh. Schmedt also hires a worker from South Dakota to help him with the harvest.

“He’s cut our families wheat since 1973,” Schmedt says. “He sort of needs a job.”

Schmedt hopes 2014 won’t be the first year he tells the man there’s no work for him in Oklahoma.

Joe Wertz / StateImpact Oklahoma

Mike Cassidy stands in front of the grain elevators his family has owned since 1921. Cassidy says this year's wheat crop will likely be the county's smallest ever.

A few miles away, in small-town Frederick, Mike Cassidy walks me around the grain elevator his grandfather built in 1921. Oklahoma’s wheat harvest starts around Memorial Day. There should be trucks coming and going, fertilizer rigs being filled with chemicals and the sound of the giant elevator screw turning.

“Just quiet as a mouse around here. There’s not a sound anywhere except the air conditioner running,” Cassidy says as the window unit on his office sputters and stops humming.

“There it goes,” he says, laughing. “It just went off. Saves us money, that’s good.”

This grain company employs about 10 people year-round, but Cassidy usually hires another 10 workers to help during the harvest. Not this year.

“We’re looking at the lowest state wheat crop since 1957, but I think for Tillman County this is the probably the worst year in history — period.”

Joe Wertz / StateImpact Oklahoma

Many farmers in southwest Oklahoma have already abandoned their wheat crops and baled what they can for hay production.

In southwest Oklahoma, you see field after field dotted with big, round bales. That’s a bad sign. It means many farmers have already abandoned their wheat and are salvaging what they can to make hay for cattle. Edwards, the wheat expert, says the state might not even have enough hay. That could be a bigger, longer-term problem for Oklahoma agriculture.

“If this drought continues and we don’t have wheat pasture this fall, it affects cow-calf producers across the entire U.S,” Edwards says.

Those producers bring their cattle to Oklahoma and other Southern Plains states to stay for the winter. If the drought continues, and pastures and hay supplies continue to dwindle, the effect could ripple.

Nationally, beef prices are the highest they’ve been since the mid-‘80s. Today’s spike in beef prices is largely fueled by a drought that started two years ago.

Schmedt, the farmer, and Cassidy, the grain elevator operator, are worried, but both of their families have survived every one of Oklahoma’s worst droughts — from the Dust Bowl devastation in the “dirty” 1930s, to the drought in the ’50s and ’70s.

“For us, this isn’t the worst — yet,” Schmedt says. “It’s bad, but it could be worse.”