Twister Truths: Does the Tornado Risk Peak After the School Day Ends?

-

Joe Wertz

Richard Rowe / Reuters/Landov

A mile-wide tornado near El Reno, Okla. on May 31, 2013.

This is part one in our Twister Truths series where we use data to kick the tires on the conventional wisdom underlying severe weather policy in Oklahoma.

In Oklahoma, state and local emergency authorities emphasize individual shelters in peoples’ homes over communal shelters in schools or other civic buildings. As we reported here, almost all the federal disaster funding the state receives has been directed to rebates for the construction of residential shelters and safe rooms.

Seven children died in the Plaza Towers Elementary School when the EF-5 tornado ripped through Moore on May 20, but Oklahoma policymakers — from Gov. Mary Fallin and Oklahoma Department of Emergency Management Director Albert Ashwood to local school officials — say a large-scale effort to build storm shelters at public schools, as other states have done, is unlikely.

One of the main reasons, they say: Most tornadoes don’t happen during the school day. In other words, the tragedy at Plaza Towers was highly unusual.

But is that claim true?

[module align=”right” width=”half” type=”pull-quote”]”Most of them don’t hit during school hours. Most often times, people have actually gone home. So, yeah, we’ve probably put a little more emphasis on people when they get home, do they have a safe place to go?”

—Albert Ashwood, director of the Oklahoma Department of Emergency Management[/module]

State emergency management officials say they emphasize individual storm shelters because most tornadoes occur during times of the day when most Oklahomans are home from work and school. And local officials have used the “peak tornado times” reasoning to justify closing community storm shelters out of concern for keeping Oklahomans at home and off the road during severe weather.

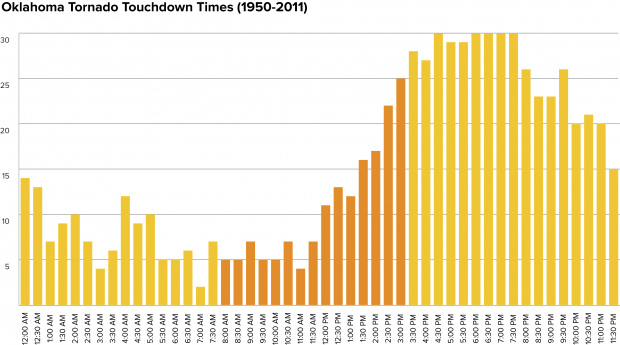

Data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association and a StateImpact analysis of the touchdown times of Oklahoma tornadoes from 1950-2011 supports both these claims:

Joe Wertz / StateImpact Oklahoma

The risk of tornadoes grows after the public school day ends, data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration show.

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration | Download data

Tornadoes have touched down at all hours, but the numbers rise dramatically after 3 p.m., when the school day ends for most Oklahoma students. The risk of tornadoes peaks from about 4:30 p.m. to 8 p.m., during rush hour and times when most Oklahomans are home from work or school.

Of the 3,390 tornadoes reported in the last 60 years, only 416 — that’s about 12 percent — have touched down during the 8 a.m. to 3 p.m. window most schools are open when they are in session. Our data analysis doesn’t account for weekends and the traditional summer break most Oklahoma students enjoy, but those factors would likely reduce the risk of school day tornadoes even more.

Superintendents in many Oklahoma school districts are considering cancelling classes and issuing “tornado days” when the threat of severe weather looms. We looked at that trend in a story last month.

Tolerance of risk when it comes to children can be a sensitive subject, of course. But if school officials were looking at this purely by the numbers, some might conclude that cancelling a whole day of school based on the threat of a tornado is overkill. Only 104 tornadoes — roughly 3 percent — touched down from 8 a.m. to noon. A data-driven superintendent might cancel only afternoon classes, rather than the whole day.