From Nuclear Fallout To Tornadoes, A Shifting View of Public Shelter Policy in Oklahoma

-

Joe Wertz

Oklahoma State Government Archives

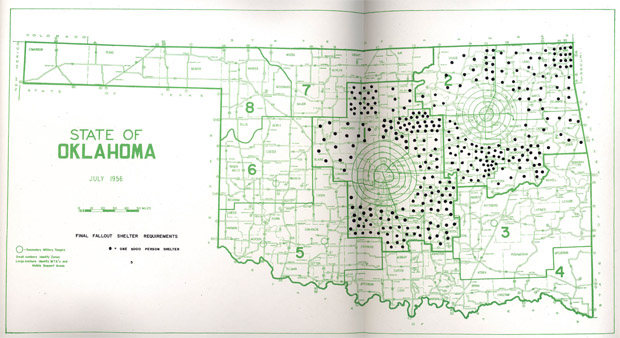

A '50s-era map from Oklahoma's Civil Defense agency shows how government officials were studying how shelters could be used to protect the public from the threat of atomic weapons.

In the 1960s, survey teams of architects and engineers started hunting across Oklahoma for places to hunker down.

They found basements and tunnels, underground parking garages and well-built structures in municipal and private buildings.

At the time, Oklahoma’s big worry was an attack from Soviet Russia. That threat never materialized, but the state is targeted by tornadoes every year. And public shelter spaces are disappearing from the map.

‘Alert Today, Alive Tomorrow’

In 1964, then-Governor Henry Bellmon said that Oklahoma had more than a half million licensed fallout shelters, and bragged that its public shelter program outpaced other those in other states.

“I would like to congratulate the Civil Defense Agency in the excellent progress made in preparing Oklahoma for a national disaster I hope will never come,” he told The Daily Oklahoman in July 1964.

By that year, more than 600,000 shelters — in structures like banks, hotels, libraries, post offices, schools and hospitals — were marked with placards emblazoned with that familiar logo: three yellow triangles in a black circle. The fallout shelter signs let the public know where they could go during a nuclear strike.

Oklahoma’s Civil Defense agency loaned out copies “Protection Factor 100” and other films to local emergency management officials to encourage them to help survey public and private buildings for community shelter space.

Helter-Shelter

But it’s getting hard for Oklahomans to find public shelter space. Statewide, community shelters are being closed. Norman is shuttering its four community shelters on July 1, the University of Oklahoma Police Department warns in a storm preparedness document.

Authorities in Edmond used to open school doors for citizens seeking public refuge, but not anymore, The Oklahoman’s Bryan Dean reports.

Joe Wertz / StateImpact Oklahoma

The Reed Center in Midwest City used to be a public shelter, but city officials voted to close all three of its community shelters in 2012. The change went into effect on Jan. 1, 2013. If you look closely, you can see the sign used to point out the entrance to the public shelter.

Midwest City officials agreed last year to close its three public shelters. One major reason: They were too popular. Overcrowding was a major concern, says the city’s Emergency Management Director Mike Bower.

During one tornado outbreak in 2011, people packed the basement of the city hall building in Midwest City. One woman went to the wrong entrance and found a locked door.

“She actually broke the window — the glass in the door — and reached in and unlocked the door,” Bower says.

Legal liability for public shelter providers isn’t an issue. In 2012, Gov. Mary Fallin signed legislation that protects businesses, individuals and other entities that provide public shelter during tornadoes and other severe weather.

But there are other problems with public shelters, like staffing, Bower says. For local governments to maintain public shelters, they have to be prepared to stage personnel who can open and manage the shelters. In Midwest City, that often meant taking police officers off the street when they were needed most, he says.

Public Fallout

Bower says he received a lot of complaints when Midwest City closed its community shelters. That doesn’t surprise David Monteyne, an architectural historian at the University of Calgary who wrote a book on the U.S. nuclear shelter program.

“Support for a public shelter program was always high,” he says.

So why couldn’t Oklahoma use some of those basements and underground spaces first conceived of as fallout shelters? Many could be used for protection in severe storms, Monteyne says. Bower agrees, but says emergency management authorities don’t want to encourage hitting the road when the sirens sound.

“We think there’s a certain amount of risk when people get in their vehicle, leave their homes, and come to a public shelter,” Bower says.

Forty-eight people were killed by Oklahoma tornadoes in May. Some died on the road as they tried to outmaneuver storms or seek refuge elsewhere, which sparked off a public debate over tornado evacuation.

Moving Target

Today, the state’s disaster philosophy is “shelter in place,” and the state emergency management authority isn’t a proponent of community shelters.

“Very rarely do you have enough lead time to actually leave your home,” Albert Ashwood, director of the Oklahoma Department of Emergency Management, tells StateImpact.

Local, state and federal officials promote private, individual shelters. But Gov. Fallin and other leaders say they aren’t going to require them. Monteyne says that mindset parallels those of the early days of the nation’s nuclear shelter program.

“In the ’50s they’re always talking about self-help. You should be digging your shelter in your backyard or building it in your basement and so on,” he says.

The nuclear threat never materialized, and the number of Americans that actually built their own bomb shelters was “miniscule,” Monteyne says.

Tornadoes, however, target Oklahoma every year. And scientists say the energy of the storm that devastated Moore on May 20 dwarfed the power of the atomic weapon that leveled Hiroshima.

Those Cold War bomb bunkers and modern day tornado shelters and safe rooms have another thing in common, Monteyne says: They mostly protect people who can afford to build them.