The Cause and Cure of Oklahoma’s Rural Doctor Deficiency Might be Money

-

Joe Wertz

Joe Wertz / NPR StateImpact

Bob Abernathy, a family practice doctor in Cordell, says the lifestyle of a rural physician doesn't appeal to young medical students.

Bob Abernathy has been a physician for about 30 years. He grew up in the country, and enjoys his life and medical practice in Cordell, a town of about 3,000 in the western part of the state.

Two of his sons are in medical school, but neither wants to follow their father’s path.

AUDIO BY LOGAN LAYDEN

The Abernathy’s are a case study. Rural Oklahoma suffers from a doctor deficiency, and medical officials say the cause and treatment are the same: money.

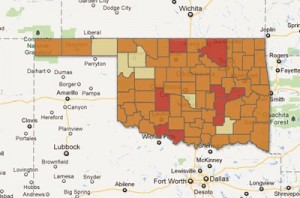

Click above to see an interactive map on primary care health shortages in Oklahoma counties. Nine entire counties have been designated primary care health shortage areas.

There are about 175 doctors for every 100,000 residents in Oklahoma, which is the second lowest ratio in the country, data from the U.S. Census Bureau show.

When it comes to primary medical care, all but six of the state’s 77 counties have “medically underserved” populations, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Nine counties — in their entirety — have been designated Health Professional Shortage Areas.

The shortage hasn’t gone unnoticed by lawmakers.

State Aid

The Physician Manpower Training Commission is one of only a few state agencies Gov. Mary Fallin wants to give more money to.

Joe Wertz / NPR StateImpact

Donna Jones, an ex-nurse who now owns the Sunshine Cafe in Cordell, says healthcare options are limited for those in rural Oklahoma.

Despite an almost entirely flat 2013 budget proposal, Fallin and her administration have proposed spending more than $3 million to establish 40 new residency programs to train physicians in rural parts of the state.

Currently, Oklahoma has five such residency programs, says Rick Ernest, the commission’s executive director. The proposed funding would increase the commission’s budget by 70 percent, and allow it to double the number of rural residency programs to 10 from five.

Training location makes a big different in medicine, Ernest says.

“If you want a rural doctor, you have to train them in a rural area,” he says, citing research showing most doctors end up practicing within 50 miles of where they were trained.

Rural residency programs help train doctors who are already committed to the idea of working in a small-town practice. But the symptoms of Oklahoma’s rural doctor deficiency are worsened by medical trends seen throughout the country.

Cash for Commitment

Rural medicine is general medicine, but many young doctors are steering away from primary care and family practice.

Russell Kohl, a family practice doctor in Vinita, says state-funded incentives for rural doctors haven't kept up with the cost of medical school.

Pay is part of it, and specialists often have more earning potential than family care doctors. That’s a big deal, because the average medical student graduates with more than $140,000 in student loan debt. And most up-and-coming doctors won’t be able to make a dent in that during their years in relatively low-paying residency programs.

Oklahoma is so desperate for rural doctors that it’s subsidizing medical students, residents and doctors.

One of the programs helps medical students with their loans by giving them $15,000 a year for up to four years. Another gives $1,000-per-month stipends to family practice residents for up to three years.

In exchange for loan assistance and stipends, med students and residents must commit to working in rural medicine for as long as they were subsidized, Ernest says. For example, a med student who received two years of loan assistance must practice for at least two years once they become doctors.

For most, the obligated commitment becomes a permanent practice, Ernest says.

Dr. Russell Kohl says he received about $40,000 in state subsidies while he was in medical school. Those stipends brought his student debt down to about $130,000, but he says medical interns at his rural practice in Vinita often owe more than $200,000 in total undergraduate and medical school debt.

The funding for the incentive program has stayed relatively constant over the years, Kohl says. The cost of becoming a doctor has not. “While it is an incentive, it’s certainly not as strong of an incentive as in the old days,” he says.

Resident Effect

The course of most young doctors is established by the time their residency ends, says Robert Valentine, a medical resident at the University of Oklahoma College of Medicine in Oklahoma City.

If they aren’t committed to rural care by then, it’s too late, he says.

Valentine, a Texan who graduated from Ross University School of Medicine in the Caribbean, says it would have been easy to stay in OKC where he’s made friends and established personal and professional relationships.

“They got me early when I didn’t know anyone in Oklahoma City,” he says about the state’s physician training commission.

Valentine is receiving the state’s residency stipend, and has committed to working in Fairfax, a town of about 1,300 in north-central Oklahoma.

State-funded incentives probably won’t change the minds of new doctors, but they can convince those on the fence, Valentine says.

“I think the program locks in the people that wanted to do it, and it encourages the people in the undecided category to at least give it a try,” he says. And once they’re in rural Oklahoma, they build relationships. “They get friendships and a house out there and they don’t want to leave.”