Classroom Contemplations: How Teachers Find Success From Failure

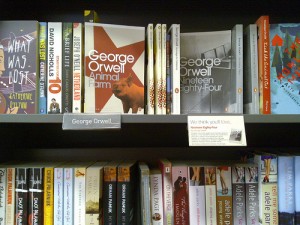

markhillary / Flickr

Paying a student to read Animal Farm didn't inspire him to read more. But he reminded the teacher of who she should be in the classroom.

Editor’s note: Names of students and teachers have been changed.

Knowing we were going to be talking about former students, Lisa Perry told me she got out some letters she had saved and read through them. The exercise inspired her to get in touch with four of her students from over 20 years ago. (“Facebook is a wonderful thing,” she told me.)

But it also showed her some themes about her teaching, things that were mentioned repeatedly by students as they expressed appreciation.

Perry told me that she saw again and again phrases like: “You really opened my eyes;” “You valued what I said;” “You took me into the world of literature and helped me relate it to life.”

But her most memorable story was what she sees as her failure as a teacher.

When she first started teaching she had a student, Robert, who didn’t listen to anything she said.

During class, he slept or he looked out the window. He simply wasn’t interested in school and he told her that, point blank. She felt, with the missionary zeal most of us have as young teachers, that there had to be a way to turn him on.

The class was reading Animal Farm and she offered Robert $20 to read the first chapter.

“What’s the catch?” he asked, full of suspicion. He told her he knew teachers, knew there was always an angle, always a catch. He expected that, after he finished the first chapter, she would withhold payment until he read another, or passed a test or completed some other task.

Perry told him there were no strings attached. The day he came in and told her he had read the chapter, he’d get $20. No questions asked.

Robert came back a few days later, told her he had read it. Perry gave him the $20.

Now, in the teacher stories we are used to, this is where Robert would get turned on by his experience of reading that first chapter. He’d love it so much that he’d read the rest of the book, then maybe everything Orwell wrote. He’d move on to read other classics and, eventually, he’d become a writer himself.

But that isn’t what happened. Robert continued to do nothing in school, and he eventually dropped out.

Several years later, after joining the military, getting married and having kids, Robert came back to find Perry.

“I just wanted you to meet my family. You were the best teacher I ever had,” he said.

She told him that she had failed him as a teacher.

“No,” he said. “You cared enough to make me read that one chapter.”

She then looked at him, expectantly, and asked “Did you ever read more?”

“No, “ he said. Then he added, “But if I ever do read a book, it will be that one.”

And it’s that eternal optimism of Perry’s, among other things in her story of Robert, that show me she is the kind of teacher we need working with our children.

“I have hope in my heart,” she told me. “And that’s what every teacher has to have. I still have hope about Robert. At least he recognizes the importance of reading and learning and, one day, who knows?”

Unfortunately, our new education policy — concerned with dots and bubbles and simple metrics — has no way to measure Perry’s effect on the many different Roberts she will encounter.

Perry recognizes this, and she recognizes that she won’t be in the profession much longer because it’s getting harder and harder for her to be the kind of teacher she wants to be.

She went back to the letters she had looked through to make her point to me.

“The things the kids remembered were not the things on those tests,” she said. “They talked about playing duck, duck goose in class. They talked about how I used to make them say ‘luscious strawberries’ over and over again just to see how it felt. These are the things that touched them.”

Though her students’ scores went up this year, thus ensuring a positive evaluation, Perry sees no value in that measure. According to her, “The thing I’m best at is getting kids to know their passion and to follow it.”

That’s who she wants to be as a teacher. But our education policy won’t let her. She’s being actively discouraged from doing what she thinks is most important as her school requires teachers to focus more and more on test preparation to the exclusion of everything else.

Our system isn’t just encouraging one narrow notion of value by relying on test scores, it’s choking out all the others. And in doing so, it’s chasing away the teachers like Perry. The teachers students often remember most.