Why Idaho’s Doctor Shortage Won’t Be Easy To Solve

- Dr. Jennifer Petrie, 40, knew she wanted to be a rural, family physician since she was in high school in Lewiston, Idaho. Her office at the Emmett Medical Center is cluttered with photos of her kids, their drawings, and stacks of patient charts.

- Emmett, Idaho resident Rebecca Smither (left) talks with Dr. Jennifer Petrie (right). Petrie is a graduate of the WWAMI program and now practices in Emmett.

- Dr. Petrie checks the progress of Rebecca Smither’s pregnancy.

- Dr. Ted Epperly is the Program Director of the Family Medicine Residency of Idaho.

- Dr. Jennifer Petrie sees patients at the Emmett Medical Center four days a week.

- Five-month-old Olivia Vandermate gets examined by Dr. Petrie during a recent check up. Petrie was Olivia’s delivery doctor and has taken care of her since.

Dr. Jennifer Petrie has known since she was a high school student in Lewiston, Idaho, that she wanted to be a rural family physician.

Petrie works at the Emmett Medical Center, less than an hour’s drive north of Boise. She sees patients four days a week in her small, sparse examining room here and also works the emergency room shift a couple times a month at the neighboring hospital.

Dr. Petrie is a generalist. She didn’t want to choose a high-paying specialty. For her, seeing all kinds of people was the most appealing thing about being a doctor.

“There is no other specialty where you can see patients in clinic, admit them to the hospital, see patients in the ER, deliver babies and do C-sections,” Petrie explains. “And for me, I love the variety, I love the continuity. I love taking care of patients from start to finish.”

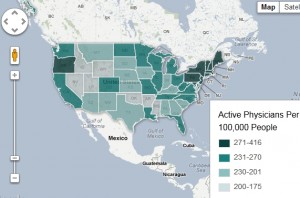

Idaho could use a lot more people like Dr. Petrie. The state has a major doctor shortage, especially in rural areas.

For every 100,000 Idahoans, there were 184 practicing doctors here in 2010, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges. That ranks Idaho 49th in the country.

Plus, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has designated all but five of Idaho’s counties as primary care Health Professional Shortage Areas.

The problem may get worse before it gets better. Many doctors in Idaho are nearing retirement.

The most current data from the American Medical Association shows 41.5 percent of all physicians in Idaho are 55 or older.

Meanwhile, there is growing demand for doctors in Idaho. That’s partially due to the state’s continuing population growth. But it’s also because of the federal health care overhaul, which is increasing the number of Idahoans who have health insurance. Even more would gain coverage if Idaho agrees to expand its Medicaid program. That’s something a state task force has been studying since the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the federal health law this summer.

“We have great concern about whether the number of providers we have now can be replaced,” says Susan Skillman, a researcher at the University of Washington in Seattle. “Let alone whether the number can grow to meet this growing demand.“

Building Idaho’s Doctor Workforce

“All this has a cumulative effect downstream,” says Dr. Ted Epperly. “And what that effect is poorer health.”

Epperly runs a family medical residency program for med students in Boise. He’s also been active in public health policy at the state and national level. He says for Idaho to begin attracting more general practitioners, education opportunities need to be expanded.

“Step one is to build enough residency programs,” Epperly says. “Step two is to increase the [number] of students training in Idaho. And step three is to scale up the number of students training either through an Idaho-based medical school or a partnered medical school.”

Idaho doesn’t have its own medical school. Instead, the state pays to send up to 20 students per year to the University of Washington. Eight more go to the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. For these students, Idaho pays the difference between in-state and out-of-state tuition.

Idaho is currently able to train 34 first-year residents in programs like Epperly’s that are based at hospitals and clinics in Boise and Pocatello.

The University of Washington partnership, known as the WWAMI program includes Wyoming, Alaska and Montana — all states without medical schools.

Since 1975, Idaho has never had more than 20 first-year seats at U-W, despite seeing the population more than double over that time. And it takes a long time to convert those seats into practicing doctors. The 28 first-year med students who started at the University of Washington or University of Utah this fall won’t be practicing medicine until at least the year 2019.

During the current fiscal year, the state spent just over $5 million to fund those medical school programs.

Funding approval for these kinds of programs starts in the state’s budget committee, of which Representative Maxine Bell (R-Jerome) is a member.

“I do know we should be doing more,” Bell says. “It’s not difficult in a budget the size of ours to carve out half a million dollars and start something. But the difficulty comes from the fact you already have so many core responsibilities in place — with demands for additional money.”

The Idaho Board of Education will ask that panel of lawmakers, including Representative Bell, to fund an additional five WWAMI positions when the Legislature convenes in January.

From Ted Epperly’s perspective, lawmakers should look at funding programs like WWAMI as an investment, not an expense.

“It’s not that the legislature doesn’t care, it’s because they’re looking at a constricted budget and making year by year decisions,” Epperly says. “It’s easy then, to miss the big picture of falling this far behind.”

Returning To Idaho

Dr. Epperly and Dr. Petrie both attended the University of Washington’s medical school, as part of the WWAMI program. They eventually came back to work in Idaho — but they weren’t required to.

About 70 percent of WWAMI graduates return to practice in Idaho. So the program doesn’t guarantee more doctors for people in the state. Idaho does offer some loan-repayment options as a way to recruit.

The Rural Healthcare Access Program is a way for Idaho communities to attract doctors by offering signing bonuses or student loan repayments. There are currently 21 grant requests totaling $595,926. The state has $183,300 available for 2013.

The Rural Physician Incentive Program is a loan repayment program for doctors who chose to practice in a rural part of the state. It’s open to doctors from all schools, though preference is given to WWAMI and University of Utah graduates. Doctors are eligible to apply for up to $50,000 of loan repayment.

Dr. Petrie is a beneficiary of that program. She gets money to pay for some of her student loans since she chose to practice in rural Emmett. But the loan help isn’t what swayed her to work in a rural part the state.

“It’s not for everyone … and there are easier ways to make a buck,” Petrie says with a laugh. “It has to be something you want to do.”

Petrie frequently stresses how being a family doctor isn’t a routine 9-to-5 job. It’s a life of late nights in the delivery room, long ER shifts and balancing the job with her own life as a wife and a mom. And that, she says, is another reason why family practice has become such a tough sell today.

“As a mom, I always feel like I’m ripping somebody off just a little bit — I’m either ripping off my patients or my kids or my husband or my family,” says Petrie. “You have to look at it as your lifestyle not just your career.”

Correction: We originally reported that three years from now, more than half of the doctors in Idaho will be 65 or older. That statistic is inaccurate, and have amended the story to read: Data from the American Medical Association shows in 2010, 41.5 percent of doctors in Idaho were 55 or older.