How Common Core Brought Attention To The Math Education Debate

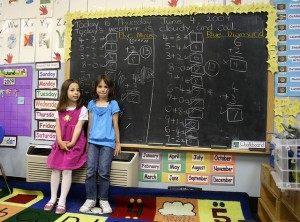

wwworks / Flickr

As schools switch to the Common Core standards, long-running teaching debates are becoming more public.

One of the by-products of states around the country adopting Common Core is that the standards have brought attention to long-running education debates that aren’t about money or testing.

This week our story looked at how Miami-Dade schools are changing math lessons to teach Florida’s Common Core-based math standards. The standards outline what students should know at the end of each grade — such as kindergarteners being able to count to 100.

As we noted in the story, many of these “new” techniques schools are adding have been around a while. And math educators have spent years debating the best ways to teach math.

Journalist Elizabeth Green cataloged what some argue are deficiencies in math education in a New York Times Magazine story headlined: “Why Do Americans Stink At Math?”

She describes a Japanese classroom, where students were encouraged to discover on their own: “Taught this new way, math itself seemed transformed. It was not dull misery but challenging, stimulating and even fun.”

Barry Garelick was so unhappy with what he was seeing in his daughter’s math lessons that he started teaching himself after retiring from the Environmental Protection Agency.

Garelick says the disadvantages of Common Core far outweigh any benefits. He responds to Green and lays out his case here:

The article is extremely well-written, which I suppose is why many people reading it (including the editors) find her arguments reasonable and would unquestioningly buy into the rather tall premise her article is built on: traditional math teaching has never worked. That’s simply not true.

But Green is not alone in mischaracterizing traditional teaching. Railing against it is fairly prevalent, and she stalwartly continues this tradition, including reciting the tired old canard of rote memorization (e.g., “having students memorize and then practice endless lists of equations”). She provides examples of math innumeracy amongst students and adults, thus focusing on failures while neglecting to investigate or even mention people for whom the traditional method of teaching did work. Such people are apparently aberrations (and that would include me).

Garelick has written a series of articles pulling apart what the Common Core standards will mean for math education. You can read them here.

The Brookings Institution compiled a list of “six myths” about math education in Green’s story, including survey data which shows American students enjoy math, and that Japanese students spend a lot of time on math outside school.

Much of the debate focuses on when and how students should be taught what’s known as the standard algorithm — the traditional method for adding, subtracting, multiplying and dividing multi-digit numbers.

Most Common Core critics argue teachers should place more emphasis on the standard algorithm and argue the standards wait too long before teaching the method most Americans know best.

Jason Zimba, one of the architects of the Common Core standards, has weighed in. Zimba says the standards do not have hard and fast rules about how and what to include in math lessons.

Zimba says if a teacher were to teach nothing but the standard algorithm then that could still adhere to the Common Core standards. But the standards do require additional concepts, such as algebra. If he were teaching, Zimba says he would lay the groundwork for the standard algorithm early in elementary school.

“As this discussion of just a single slice of the math curriculum illustrates,” Zimba concludes, “teachers and curriculum authors following the standards still may, and still must, make an enormous range of decisions.”