Anatomy Of An English Class: How The Common Core Is Shaping Instruction For One Miami Teacher

Editor’s note: This story was authored by Sarah Carr for The Hechinger Report.

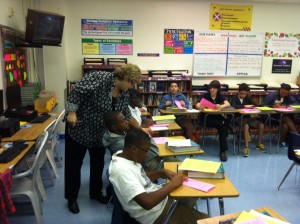

MIAMI—English instructor Lois Seaman often speaks bluntly to her middle-school students about the increased expectations they will face under the new Common Core curriculum standards. “It’s like you are looking at this under a microscope; glean all you can from this text,” she told a class of eighth graders as they studied a passage from “Flowers for Algernon” by Daniel Keyes. “Common Core says, ‘Read like a detective and write like an investigative reporter.’”

Seaman’s students at Richmond Heights Middle School will still be tested on the old state standards this school year. But like many of her colleagues, Seaman has already started adjusting her teaching approach to meet the new standards. Here are a few of her strategies, culled from her own research and materials and guidance provided to teachers by the Miami-Dade school district and the state:

Asking students to read multiple texts on the same theme:

This year, Seaman will assign the short story “The School Play” by Gary Soto, which includes a reference to the Donner Party, a group of American pioneers trapped in the Sierra Nevada snow during their mid 19th-century migration to California.

Students will also read excerpts from diaries written by members of the Donner party in an effort to give them added insight into the short story. In addition, “Raymond’s Run,” a story about a girl who cares for her mentally disabled brother, will be accompanied by the poem “Brother and Sister” by Lewis Carroll.

The pairings are part of Seaman’s effort to ensure students can analyze and write on multiple readings that explore similar themes—a key requirement of the Common Core.

Introducing more challenging readings:

Since the new standards call for teachers to introduce more challenging readings at younger grades, Seaman looked for texts that would force her middle school students out of their comfort zone in some way.

Lewis Carroll’s “Brother and Sister,” for instance, engages them through humor (and is also focused on a theme many students can relate to: sibling rivalry). But it contains a mixture of antiquated and advanced words—such as mutton, wherefore, prudent, and indignantly—that Seaman knew many of her students would find difficult.

Requiring students to analyze readings independently:

When Seaman’s eighth graders started reading “Flowers for Algernon” this fall, she asked them to dive in on their own. The class did not read the opening passage together or review biographical information about the author, as they might have done in the past. Instead, the students read the first paragraph silently and then discussed it with a partner (in a new twist, Seaman told them to have an “intellectual” conversation rather than simply saying, “discuss”).

At the end of those conversations, the students turned in bulleted lists with their observations about genre, setting, main characters, and story conflict. If Florida uses the PARCC exam (which appears increasingly unlikely) or something like it, the test will likely require students to write analytical essays on clusters of readings. Partly as a result, Seaman is trying to ensure students feel comfortable undertaking literary analysis without much prior background information, context, or large group discussion.

Assigning more analytical writing exercises:

Over the course of her classes, Seaman repeatedly reminds students to support almost anything they write with evidence.

“It can never just be about yourself,” she tells them. “We can’t just throw things out. We have to back them up.” She hammers this point home deliberately. The PARCC exam will require students to write essays citing evidence from multiple readings.

By contrast, Florida’s current standardized test focuses just on expository and persuasive writings; citing facts and evidence from the texts isn’t weighted nearly as heavily as it will be under PARCC. Seaman is trying to encourage even one of her sixth grade classes comprised largely of English language learners to focus more on evidence in their writing, advising them to start sentences with, “I know this because….”

This story was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, nonpartisan education-news outlet affiliated with Teachers College, Columbia University.