Why Some Schools Are Throwing Out The Old Grading System

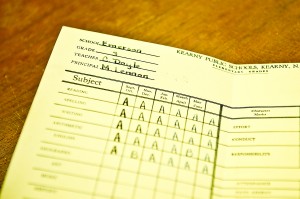

Lauren Casselberry / The New Jersey Journal/Landov

Minnesota school districts are among those scrapping traditional grading systems in favor of one tied to standards.

Some Minnesota school districts have found that student scores on state standardized tests were not matching grades earned for classroom work, according to the St. Paul Pioneer-Press.

To correct the problem, districts are switching to standards-based grading which ties student performance to what they are expected to know.

Under the new system, students are allowed to retake tests and submit work again. Only the most recent grade counts. Students are graded on a 1 to 4 scale. A 1 means students do not meet the standards, while a 4 means students exceed the standards.

Educators say more districts are adopting standards-based grading:

School grading tends to favor students who “do school well,” as Osseo’s curriculum and instruction director, Wendy Biallas-Odell, put it: They show up on time, raise their hands, complete assignments and volunteer for extra credit. In some classrooms, students can make headway toward an A that way — without proving they have mastered the material.

“Some of the things that have gone into grading traditionally have nothing to do with learning,” said Steve Unowsky, the middle grades assistant superintendent in St. Paul, where Hazel Park Middle School and Murray Junior High have piloted standards-based grading.

To some educators, these traditional practices fly in the face of a national push to show students are hitting learning targets on their way to more advanced courses and college. They also make grades less-than-informative.

Online schools have adopted similar grading schemes. Former Gov. Jeb Bush has said schools should put less emphasis on “seat time” — hitting a required amount of classroom instruction — and instead let students advance when they prove they have mastered the concepts.

The downside, according to Minnesota schools, is that the new system can be more difficult to understand. School districts need to explain the change to parents and students.

And as one parent noted: If it’s more difficult to earn what traditionally would be considered a ‘A,’ then the system might favor those satisfied with earning a “gentleman’s B.”

“This hurts the overachievers and helps the underachievers,” Steve McCuskey said.