Reporter’s Notebook: Tracing the tracks of the oil trains

-

Susan Phillips

Trudy E. Bell

An oil train passes apartments in the University Village neighborhood of Chicago. The trains travel through Chicago on their way to East Coast refineries like those in Philadelphia and South Jersey. Bell

Driving south on Lakeshore Drive through the Lakeview section of Chicago, it’s easy to ignore the city’s role in industrial transport. Lake Michigan looks placid and blue. People are riding their bikes along the shore, or strolling, or picnicking. It’s a pleasant, sunny Sunday evening after a long hard winter. Chicagoans bustle through new parks and grand museums. But keep going, and avoid google maps’ efforts to divert you to the highway, and it’s soon obvious how this place serves as the nation’s bottleneck for oil trains.

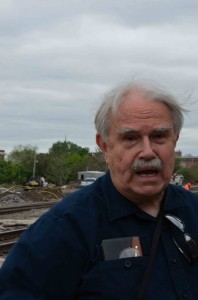

Chuck Quirmbach, a seasoned public radio reporter from Wisconsin, served as my chauffeur and tour guide, pointing out old and new, like the city’s Millennium Park.

“Don’t know why they built that,” he said, adding that the city had plenty of other nearby parks.

Quirmbach, with his head of thick white hair usually framed by a pair of headphones, microphone in hand, is one of those reporters who has probably covered every kind of story imaginable. And he’s still curious. We stay on route 41, which takes us through the South Side, hugging Lake Michigan. But the green spaces along the lake soon give way to industry young and old. Or new parks interspersed with old decaying industry. At one point we drive by thick masonry walls, abandoned to weed trees, another form of greening.

We continue on route 20, where we pass through towns with Latino groceries and boarded up houses. At some point we cross into northwest Indiana, pass through Hammond, famous for its casino “Horseshoe Hammond,” and make our way through the back roads of the BP oil refinery. We’re on our way to the Ameristar casino hotel in East Chicago Indiana, where we’ll meet up with a dozen other reporters also interested in oil trains, pipelines and Bakken crude.

The Ameristar looks like some state lawmaker’s idea of job creation. It sits surrounded by freight rail tracks, tank farms, and a steel plant. It’s a third rate casino, sending free busses into Chicago’s Chinatown every hour. The friendly staff is clearly under orders to emphasize customer service.

Looking confused, a man in a bellhop uniform greets me and offers to take me up to my room. He loves to talk. He says,”You’re going to love it here!” He’s proud of the beds, custom made. But his chief selling point is the view. He parts the curtains and points out the steel mill. Across a small marina from the hotel, smoke is billowing from several stacks. The steel plant stretches as far as the eye can see. Lake Michigan, beyond it, is blocked from view. The best, he says, is the BP plant just to the left of the plant, in Whiting, Indiana.

“Do you see those three new towers?” he asks. “Those are brand new. They take sand out of oil from Canada. And it makes us energy-independent.” Perhaps detecting a bit of caution on my face he adds: “Don’t worry, they don’t pollute because if they do, they would be fined a lot of money. And they test the water every day.”

What water, I wasn’t sure. But last year the plant spilled 1,600 gallons of crude into Lake Michigan.

Built back in 1889 by Standard Oil, Whiting’s BP plant has been revived by Canadian tar sands. The refinery is BP’s largest in the U.S., converting 413,000 barrels of crude a day to supply cars, trucks, airplanes, tractors and propane tanks. The company says the plant provides about 60,000 jobs. The day I got there was the final day of a 3-month strike over safety issues.

Oil trains are on everyone’s minds these days. The century’s old railroad tracks that once carried the nation’s industrial cargo follow rivers and waterways, which now abut brand-new million-dollar condos in cities like Philadelphia and Chicago. These once quiet and quaint tracks now carry potentially deadly cargo.

Trudy E. Bell

The BP refinery in Whiting, Indiana now processes Canadian tar sands with the help of a new coker that looms above the community of Marktown. Bell

Chicago it turns out, is where all the oil trains that come from Canada and North Dakota converge. Their journeys along Burlington Northern Santa Fe tracks, or Canadian National lines, end at the city’s rail yards near downtown, where they switch to either Norfolk Southern or CSX tracks for their trip east.

So I took a trip to Chicago, along with about a dozen other journalists interested in learning more about the transportation of energy and its full-to-capacity infrastructure. It was part of a workshop put on by the Institute for Journalism and Natural Resources.

Just before the switch to the eastbound lines, the trains pass by the home of Tony Phillips, in the University Village neighborhood of Chicago. In his bedroom window facing the tracks is a sign that reads “No More Oil Trains.” Standing on the platform at Halsted Station, Phillips remembers the first time he noticed the trains rolling by on tracks parallel to busy commuter rail lines.

Winnie Bird

Tony Phillips lives right next to the train tracks in University Village that now carry oil trains.

“I started seeing these trains on a regular basis,” said Phillips. “And then Lac-Megantic occurred and my interest was piqued.”

Lac-Megantic was the site of an oil train explosion in July 2013. Forty-seven townspeople died in the explosion, which burned so hot five of the bodies were never recovered.

Phillips pointed to brand new condos getting built along the tracks, estimating that about 1,000 people could live within half a mile, the distance federal authorities say would need evacuated in case of an explosion or fire. He takes out his binoculars.

“Yes, we have an oil train,” said Phillips. “It’s going to present itself.”

The train lumbers by at a slow pace, screeching, and seems to go on forever.

“Sometimes in the middle of the night I can hear the 30 feet of slack in a 100 car train taken up as a rip of noise running the full length of the train taking a couple of seconds, and that’s when my house shudders,” says Phillips. “I can feel it in the ground and immediately thereafter there’s a slosh effect, there’s a bathtub effect in the train, and that’s a little frightening. if you’re up at three in the morning, ghosts attend everything. It’s a little spooky.”

Those same oil trains that frighten Phillips also inch their way across Pennsylvania, clog Philadelphia’s rail lines, and end up at refineries like Philadelphia Energy Solutions in southwest Philly, or PBF Energy in Paulsboro.

Those ancient right-of-ways are also convenient places to create new green spaces like parks and bike paths through crowded post-industrial American cities. For some, the arrival of black tank cars bring hope that the U.S. can reclaim its industrial past. For others, images of the rolling fires of Lac Megantic haunt them in their sleep.

This includes Tom Weisner, mayor of the city of Aurora, which lies about 35 miles west of Chicago. At 200,000 people, it’s the second largest city in Illinois.

“Frankly, a derailment in or around our downtown area would be disastrous,” said Weisner. “People talk about preparedness. You can have the foam located in one or more locations throughout the city. You can have the resources galore. But it’s the matter of getting them to the site, which you only find out about after the fact.”

Weisner says his first responders are as ready as they’ll ever be. But in most cases, oil train fires are left to burn. The only way to put them out is to lay foam on top of the fire.

On our way to meet with the mayor earlier that morning, we drove beneath an overpass with a long train of oil tank cars lumbering above. Below, the street had been marked off with orange cones in one section where debris had fallen from the railroad bridge above. A man in a bright yellow safety vest used a push broom to sweep up chunks of concrete.

Back at the casino, a new bell hop greeted me. Sizing me up as someone not interested in playing the slots, he asked if I was there on business with the U.S. Steelworkers. No, I said, I’m a journalist. I’m reporting on oil trains and pipelines.

“Oh,” he said. “That’s good, sweetheart. I hope you asked those guys at BP why they mess everything up.”